What is charisma when you see it? Charismatic leaders are among the most famous persons of past history and today. What was it like to meet a charismatic leader? You fell under their spell. How did they do it?

One of the best-described of all charismatic leaders is Jesus. About 90 face-to-face encounters with Jesus are described in the four gospels of the New Testament.

Notice what happens: Jesus is sitting on the ground, teaching to a crowd in the outer courtyard of the temple at Jerusalem. The Pharisees, righteous upholders of traditional ritual and law, haul before him a woman taken in adultery. They make her stand in front of the crowd and say to Jesus: “Teacher, this woman was caught in the act of adultery. The Law commands us to stone her to death. What do you say?”

The text goes on that Jesus does not look up at them, but continues to write in the dirt with his finger. This would not be unusual; Archimedes wrote geometric figures in the dust, and in the absence of ready writing materials the ground would serve as a chalkboard. The point is that Jesus does not reply right away; he lets them stew in their uneasiness.

Finally he looks up and says: “Let whoever is without sin cast the first stone.” And he looks down and continues writing in the dust.

Minutes go by. One by one, the crowd starts to slip away, the older ones first-- the young hotheads being the ones who do the stoning, as in the most primitive parts of the Middle East today.

Finally Jesus is left with the woman standing before him. Jesus straightens up and asks her: “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?”

She answers: “No one.” “Then neither do I condemn you,” Jesus says. “Go now and sin no more.” (John 8: 1-11)

Jesus is a master of timing. He does not allow people to force him into their rhythm, their definition of the situation. He perceives what they are attempting to do, the intention beyond the words. And he makes them shift their ground.

Hence the two periods of tension-filled silence; first when he will not directly answer; second when he looks down again at his writing after telling them who should cast the first stone. He does not allow the encounter to focus on himself against the Pharisees. He knows they are testing him, trying to make him say something in violation of the law; or else back down in front of his followers. Instead Jesus throws it back on their own consciences, their inner reflections about the woman they are going to kill. He individualizes the crowd, making them drift off one by one, breaking up the mob mentality.

The Micro-sociology of Charisma

Jesus is a charismatic leader, indeed the archetype of charisma.

Although sociologists tend to treat charisma as an abstraction, it is observable in everyday life. We are viewing the elements of it, in the encounters of Jesus with the people around him.

I will focus on encounters that are realistic in every respect, that do not involve miracles-- about two-thirds of all the incidents reported. Since miracles are one of the things that made Jesus famous, and that caused controversies right from the outset, some miracles will be analyzed. I will do this mostly at the end.

(1) Jesus always wins an encounter

(2)Jesus is quick and absolutely decisive

(3) Jesus always does something unexpected

(4) Jesus knows what the other is intending

(5) Jesus is master of the crowd

(6) Jesus’ down moments

(7) Victory through suffering, transformation through altruism

(Appendix) The interactional context of miracles

(1) Jesus always wins an encounter

When Jesus was teaching in the temple courts, the chief priests and elders came to him. “By what authority are you doing these things?” they asked. “And who gave you this authority?”

Jesus replied: “I will also ask you a question. If you answer me, I will tell you by what authority I am doing these things. John’s baptism-- where did it come from? Was it from heaven, or of human origin?”

They discussed it among themselves and said, “If we say, ‘From heaven,’ he will ask, ‘Then why don’t you believe him?’ But if we say, ‘Of human origin,’ the people will stone us, because they are persuaded that John was a prophet.”

So they answered, “We don’t know where it was from.”

Jesus said, “Neither will I tell you by what authority I am doing these things.” (Matthew 21: 23-27; Luke 20: 1-8) He proceeded to tell the crowd a parable comparing two sons who were true or false to their father. Jesus holds the floor, and his enemies did not dare to have him arrested, though they knew the parable was about themselves.

Jesus never lets anyone determine the conversational sequence. He answers questions with questions, putting the interlocutor on the defensive. An example, from early in his career of preaching around Galilee:

Jesus has been invited to dinner at the house of a Pharisee. A prostitute comes in and falls at his feet, wets his feet with her tears, kisses them and pours perfume on them. The Pharisee said to himself, “If this man is a prophet, he would know what kind of woman is touching him-- that she is a sinner.”

Jesus, reading his thoughts, said to him: “I have something to tell you.” “Tell me,” he said. Jesus proceeded to tell a story about two men who owed money, neither of whom could repay the moneylender. He forgives them both, the one who owes 500 and the one who owes 50. Jesus asked: “Which of the two will love him more?” “The one who had the bigger debt forgiven,” the Pharisee replied. “You are correct,” Jesus said. “Do you see this woman? You did not give me water for my feet, but this woman wet them with her tears and dried them with her hair... Therefore her many sins have been forgiven-- as her great love has shown.”

The other guests began to say among themselves, “Who is this who even forgives sins?” Jesus said to the woman, “Your faith has saved you; go in peace.” (Luke 7: 36-50)

Silencing the opposition

Jesus always gets the last word. Not just that he is good at repartee, topping everyone else; he doesn’t play verbal games, but converses on the most serious level. What it means to win the argument is evident to all, for audience and interlocutor are amazed, astounded, astonished: they cannot say another word.

He takes control of the conversational rhythm. For a micro-sociologist, this is no minor thing; it is in the rhythms of conversation that solidarity is manifested, or alienation, or anger. Conversations with Jesus end in full stop: wordless submission.

His debate with the Sadducees, another religious sect, ends when “no one dared ask him any more questions.” (Luke 20: 40)

When a teacher of the Law asks him which is the most important commandment, Jesus answers, and the teacher repeats: “Well said, teacher, you are right in saying, to love God with all your heart, and to love your neighbour as yourself is more important than all burnt offerings and sacrifices.” Jesus said to him, “You are not far from the kingdom of God.” And from then on, no one dared ask him any more questions. (Mark 12: 28-34)

A famous argument ends the same way: The priests send spies, hoping to catch Jesus in saying something so that they might hand him over to the Roman governor. So they asked: “Is it right for us to pay taxes to Caesar or not?”

Jesus knowing their evil intent, said to them, “Show me the coin used to pay taxes.” When they brought it, he said, “Whose image is on it?” “Caesar’s,” they replied. “Then give to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s.”

And they were astonished by his answer, and were silent. (Luke 20: 19-26; Matthew 22: 15-22)

As with the woman taken in adultery, again there is an attempted trap; a turning of attention while everyone waits; and a question-and-reply sequence that silences everyone. Jesus does not just preach. It is at moments like this, drawing the interlocutor into his rhythm, that he takes charge.

(2) Jesus is quick and absolutely decisive

As his mission is taking off in Galilee, followers flock to hear him. Some he invites to come with him. It is a life-changing decision.

A man said to him: “Lord, first let me go and bury my father.” Jesus replied: “Follow me, and let the dead bury their dead.”

It is a shocking demand. In a ritually pious society, there is nothing more important that burying your father. Jesus demands a complete break with existing social forms; those who follow them, he implies, are dead in spirit.

To another would-be recruit he underlines it: “No one who puts a hand to the plow and looks back is fit for service in the kingdom of God.” (Luke 9: 57-62; Mark 8: 19-22)

Charisma is total dedication, having it and imparting it to others. There is nothing else by which to value it. Either do it now, or don’t bother.

This is how Jesus recruits his inner circle of disciples. He is walking beside the Sea of Galilee, and sees Simon and Andrew casting their net into the lake. “Come, follow me,” Jesus said, “and I will make you fishers of men.” At once they left their nets and followed him. A little further on, he sees James and his brother John preparing their nets. Without delay he called them, and they left their father in the boat and followed him. (Mark 1: 16-20; Matthew 4: 8-22. Luke 5: 1-11 gives a longer story about crowds pressing so closely that Jesus preaches from a boat, but it ends with the same abrupt conversion; here the influence of the crowd is more visible than in the truncated versions.)

Jesus recruits not from the eminent, but from the humble and the disreputable. Among the latter are the tax collectors, hated agents of the Roman overlord. There is the same abrupt conversion: As Jesus is passing along the lake with a large crowd following, he sees a man sitting at the tax collector’s booth. “Follow me,” Jesus said, and the man got up, left everything, and followed him.

They have a banquet at his house (Luke 5: 27-32; Mark 1: 13-17; Matthew 9: 9-13), with many tax collectors and others eating with the disciples. The Pharisees complained, “Why do you eat and drink with tax collectors and sinners?” Jesus replied, “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance.”

Jesus perceives who will make a good recruit, and who will not.

(3) Jesus always does something unexpected

Being with Jesus is exciting and energizing, among other reasons because he is always surprising. He does not do or say just what other people expect; even when they regard him as a prophet and a miracle-worker, there is always something else.

Pharisees and teachers of the law who had come from Jerusalem gathered around Jesus and saw some of his disciples eating food with hands that were defiled. They asked Jesus, “Why do your disciples break the tradition of the elders? They don’t wash their hands before they eat!”

Jesus replied, “You Pharisees clean the outside of the cup and dish, but inside you are full of greed and wickedness. You foolish people! Did not the one who made the outside make the inside also? But as to what is inside you-- be generous to the poor, and everything will be clean for you.”

He goes on with further admonitions, and his opponents accuse Jesus of insulting them. Jesus called the crowd to him to hear. The disciples came to him privately and asked, “Do you know that the Pharisees were offended when they heard this?” Jesus replied: “Leave them; they are blind guides. If the blind lead the blind, both will fall into a pit.”

Peter said, “Explain the parable to us.” “Are you still so dull?” Jesus asked them. “Don’t you see that whatever enters the mouth goes into the stomach and then out of the body? ... But out of the heart come evil thoughts-- murder, adultery, sexual immorality, theft, false testimony, slander. These are what defile a person; but eating with unwashed hands does not defile them.” (Matthew 15: 1-20; Mark 7: 1-23; Luke 11: 37-54)

Ritual purification is what concerns the pious and respectable of the time; Jesus meets an accusation with a stronger one. Even his closest disciples do not escape the jolt. “Are you still so dull? Don’t you see?” Everyone has to be on their toes when they are around this man.

How does Jesus generate an unending stream of jolts? He has a program: mere ritual and the righteous superiority that goes with it is to be brought down and replaced by humane altruism, and by spiritual dedication. When his encounters involve miracles, or rather people’s reaction to them, the program bursts expectations: On a Sabbath Jesus was teaching in a synagogue, and a women was there who was crippled for 18 years, bent over and unable to straighten up. Jesus called her forward and said to her, “Woman, you are set free from your infirmity.” Then he put his hands on her, and immediately she straightened up and praised God.

Indignant that Jesus had healed on the Sabbath, the synagogue leader said to the people, “There are six days for work. So come and be healed on those days, not of the Sabbath.”

Jesus answered him, “You hypocrites! Doesn’t each of you on the Sabbath untie your ox or donkey from the stall and lead it out to give it water? Then should not this woman, a daughter of Abraham... be set free on the Sabbath from what bound her?” When he said this, all his opponents were humiliated, but the people were delighted. (Luke 13: 10-17. Similar conflicts about healing on the Sabbath are in Luke 6: 6-11; Matthew 12: 1-14; and Luke 14: 1-6, which ends by silencing the opposition.)

It is not the miracle that is at issue; what makes the greater impression on the crowd is Jesus’ triumph over the ritualists. It is also what leads to the escalating conflict with religious authorities, and ultimately to his crucifixion.

Nearer the climax, Jesus enters Jerusalem with a crowd of his followers who have traveled with him from Galilee in the north, picking up enthusiastic converts along the way. He enters Jerusalem in a triumphant procession, greeted by crowds waving palm fronds. Next morning he goes to the temple.

In the temple courts he found people selling cattle, sheep and doves, and others sitting at tables exchanging money. So he made a whip out of cords, and drove all from the temple courts, both sheep and cattle; he scattered the coins of the money changers and overturned their tables. To those who sold doves he said, “Get these out of here! Stop turning my Father’s house into a market!” (Another text quotes him:) “Is it not written, ‘My house will be called a house of prayer for all nations’? But you have made it ‘a den of thieves.’”

The chief priests and teachers of the law heard this and began looking for a way to kill him, for they feared him, because the whole crowd was amazed at his teaching. (John 2: 13-16; Mark 11: 15-19)

One text gives a tell-tale detail: Immediately after entering Jerusalem in the palm-waving crowd, Jesus went into the temple courts.

He looked around at everything, but since it was already late, he went out to the nearby village of Bethany with the Twelve. (Mark 11: 11)

Jesus clearly intends to make a big scene; he is going to do it at the height of the business day, not in the slack time of late afternoon when the stalls are almost empty. Jesus always shows strategic sense.

Why are the animals and the money changers in the temple in the first place? Because of ritualism; the animals are there to be bought as burnt sacrifices, and the money changers are to facilitate the crowd of distant visitors. But also it was the case, throughout the ancient world and in the medieval as well, that temples and churches were primary places of business, open spaces for crowds, idlers, speculators, merchants of all sorts. In Babylon and elsewhere the temples themselves acted as merchants and bankers (and may have originated such enterprises); in Phoenicia and the coastal cities of sin anathema to the Old Testament prophets, temples rented out prostitutes to travelers; Greek temples collected treasure in the form of bronze offerings and subsequently became stores of gold. Jesus no doubt had all this in mind when he set out to cleanse the temple of secular transactions corrupting its pure religious purpose.

Jesus is not just shocking on the large public scene; he also continues to upend his own disciples’ expectations. In seclusion at Bethany, he is reclining at the dinner table when a woman came with an alabaster jar of expensive perfume. She broke the jar and poured the perfume on his head.

Some of the disciples said indignantly to each other, “Why this waste of perfume? It could have been sold for more than a year’s wages and the money given to the poor.” And they rebuked her harshly.

“Leave her alone,” Jesus said. “She has done a beautiful thing to me. The poor you will always have with you, and you can help them any time you want.

But you will not always have me. She did what she could. She poured perfume on my body beforehand to prepare me for my funeral.” (Mark 14: 1-10; Matthew 26: 6-13)

A double jolt. His disciples by now have understood the message about the selfishness of the rich and charity to the poor. But there are circumstances and momentous occasions that transcend even the great doctrine of love thy neighbour. Jesus is zen-like in his unexpectedness. There is a second jolt, and his disciples do not quite get it. Jesus knows he is going to be crucified. He has the political sense to see where the confrontation is headed; in this he is ahead of his followers, who only see his power.

(4) Jesus knows what the other is intending

Jesus is an intelligent observer of the people around him. He does not have to be a magical mind-reader. He is highly focused on everyone’s moral and social stance, and sees it in the immediate moment. Charismatic people are generally like that; Jesus does it to a superlative degree.

He perceives not just what people are saying, but how they are saying it; a socio-linguist might say, speech actions speak louder than words.

So it is not surprising that Jesus can say to his disciples at the last supper, one of you will betray me, no doubt noting the furtive and forced looks of Judas Iscariot. Or that he can say to Peter, his most stalwart follower, before the cock crows you will have denied me three times-- knowing how strong blustering men also can be swayed when the mood of the crowd goes against them in the atmosphere of a lynch mob. (Mark 14: 17-31; Matthew 26: 20-35; John 13: 20-38)

Most of these examples have an element of Jesus reading the intentions of his questioners, as when they craftily try to trap him into something he can be held liable for. Consider some cases where the situation is not so fraught but he knows what is going on: Invited to the house of a prominent Pharisee, Jesus noticed how the guests vied for the places of honor at the table.

He told them a parable: “When someone invites you to a wedding feast, do not take the place of honor, for a person more distinguished than yourself may have been invited... and, humiliated, you will have to move to the least important place. But when you are invited, take the lowest place, so that when your host comes, he will say to you, ‘Friend, move up to a better place.’ Then you will be honored in the presence of all the other guests. For those who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.” Then Jesus said to the host, “...When you give a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind, and you will be blessed. Although they cannot repay you-- as your relatives and rich friends would by inviting you back-- you will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous.” (Luke 14: 7-16)

It is an occasion to deliver a sermon, but Jesus starts it with the situation they are in, the unspoken but none-too-subtle scramble for best seats at the table. And he makes a sociological point about the status reciprocity involved in the etiquette of exchanging invitations.

Jesus sees what matters to people. A rich young man, inquiring sincerely about his religious duties, ran up to Jesus and fell on his knees. “Good teacher,” he asked, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

“Why do you call me good?” Jesus asked, as usual answering a question with a question.

“No one is good-- except God alone. You know the commandments: ‘You shall not murder, nor commit adultery, nor steal, nor give false testimony, nor defraud; honor your father and mother.’”

“Teacher,” he declared, “all these I have kept since I was a boy.” Jesus looked at him. “One thing you lack,” he said. “Go, and sell everything you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come and follow me.”

At this the man’s face fell. He went away sad, because he had great riches. (Mark 10: 17-22; Luke 18: 18-30; Matthew 19: 16-26)

Jesus knows who to recruit, who is ready for instantaneous commitment, by watching them. As his crowd of followers passed through Jericho, a chief tax collector wanted to see Jesus, but because he was short he could not see over the heads of the crowd. So he ran ahead and climbed a tree. When Jesus reached the spot, he looked up and said to him, “Zacchaeus, come down immediately. I must stay at your house today.” People began to mutter, “He has gone to be the guest of a sinner.” But Zacchaeus said to Jesus, “Here and now I give half my possessions to the poor, and if I have cheated anyone, I will pay him back four times the amount.” (Luke 19: 1-10)

This is the theme again, recruiting among sinners. But Jesus is a practical leader as well as an inspirational one. He normally sends out forerunners to line up volunteers to lodge and feed his traveling followers (Luke 10: 1-16; Matthew 26: 17-19;); in this case, he has picked out a rich man (class distinctions would have been very visible), and someone who is notably eager to see him. No doubt Jesus’ perceptiveness enables him to pick out early disciples like Peter and the other fishermen.

Jesus’ perceptiveness helps explain why he dominates his encounters. He surprises interlocutors by unexpectedly jumping from their words, not to what conventionally follows verbally, but instead speaking to what they are really about, skipping the intermediate stages.

(5) Jesus is master of the crowd

The important events of Jesus’ life mainly take place in crowds. Of 93 distinct incidents of Jesus’ adult life described in the gospels, there are at most 5 occasions when he is with three or fewer other people.*

When he is outdoors, he is almost entirely surrounded by crowds; in the early part of his mission in Galilee he periodically escapes the crowds by going out on boats and climbing remote mountainsides in order to pray in solitude. The crowds increase and follow him wherever he goes. Indoors, 6 incidents take place at banquets, including an overflow wedding party; 3 in synagogues; 2 are hearings before public authorities. There are also 9 occasions when he is backstage with his disciples, although often there is a crowd outside and people get in to see him.

Altogether, for Jesus a relatively intimate gathering was somewhat more than a dozen people, and most of his famous interactions took place with twenties up through hundreds or even several thousands of people amidst whom he was the center of attention.

*John 1: 35-42; two of John the Baptist’s disciples seek out Jesus after John has pointed him out in the crowd of the Baptist’s own followers, and the two spend the afternoon visiting Jesus where he stays. This is before Jesus is baptized and starts his own mission.

Luke 9: 28-30; Matthew 17: 1-13; Mark 9: 2-13; Jesus with three disciples go up on a mountain to pray, where they see him transfigured.

John 4: 31-42; Jesus meets a Samaritan woman at a well while his disciples have gone into town for provisions; they have a one-on-one conversation, and many in her village become believers that he is the Savior of the world, among other reasons because he has broken the taboo on Jews associating with Samaritans.

John 3: 1-21; Jesus is visited at night by a Pharisee who is a member of the ruling council; no one else is mentioned as present, although the conversation leads to some of the most famous Bible passages, “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” Presumably someone heard this and wrote it down; not unlikely since Jesus always stayed in a house full of his disciples. Mark 14: 32-42; Matthew 26: 36-46; Jesus goes with his disciples (the Twelve minus Judas) plus at least some others to pray at Gethsemane. He then takes three close followers, goes a little further into the garden, and prays in anguish while the others fall asleep. This is the one important place in the narration where Jesus is alone, and the one time that he shows anxiety. I do not count the 40 days he spent praying in the wilderness before beginning his ministry; the only incidents described for this period are not pinned down in time and circumstance and all involve talking with the devil. I will discuss these below in the section on apparitions.

Crowds are a major source of Jesus’ power. There is a constant refrain: “The crowds were amazed at his teaching, because he taught as one who had authority, and not as their teachers of the law.” (Matthew 7: 29) His enemies the high priests are afraid of what his crowd of followers will do if they attack Jesus. As the challenge mounts in Jerusalem on the last and greatest day of the Passover festival, Jesus preaches in the temple courts in a loud voice, “Let anyone who is thirsty come to me and drink.” The crowds are divided on whether he is the Messiah. The temple guards retreat to the chief priests, who ask them, “Why don’t you arrest him?” “No one ever spoke the way this man does,” the guards reply.

“The mob knows nothing of the law,” the Pharisees retort, “there is a curse on them.” (John 7: 37-49)

Judas’ betrayal of Jesus consists in telling the priests when and where Jesus will be alone, so that he can be arrested. Alone, relatively speaking; there are at least a dozen of his followers with him at Gethsemane, but it is for arranging the absence of the crowd that Judas receives his 30 pieces of silver. (Luke 22: 2-6) The signal is to mark Jesus with a kiss, so the guards will know whom to seize in the dark.

Charismatic leaders live on crowds. There is no such thing as a charismatic leader who is not good at inspiring crowds; and the micro-sociologist adds, being super-energized by them in turn. Crowd and leader are parts of a circuit, emotional intensity and rhythmic coordination flowing from one to the other: charisma as high-amp electric current. It is what the Bible, especially in the Book of Acts, calls the holy spirit.

Jesus as archetype of the charismatic leader also shows how a charismatic movement is organized. His life moves in three spheres: crowds; the inner circle of his twelve disciples; and withdrawing into solitude. The third of these, as noted, does not figure much in the narration of important events; but we can surmise, from sociological research on prayer, that he reflects in inner dialogue on what is happening in the outer circles, and forms his resolve as to what he will do next.

The inner circle has a practical aspect and a personal aspect. Jesus recruits his inner disciples, the Twelve, because he wants truly dedicated followers who will accompany him everywhere. That means giving up all outside commitment, leaving occupation, family, home town. It means leaving behind all property, and trusting that supporters will bring them the means of sustenance, day after day. In effect, they are monks, although they are not called that yet. Thus the inner circle depends on the outer circle, the crowds of supporters who not only give their emotion, but also food, lodging, whatever is needed. Jesus is the organizer of a movement, and he directs his lieutenants and delegates tasks to them. Early in his mission, when the crowds are burgeoning, he recognizes that “the harvest is plentiful but the workers are few” and sends out the Twelve to preach and work miracles on their own, accelerating the cascade of still more followers and supporters. (Luke 9: 1-6; Mark 6: 7-13; Matthew 9: 35-38; 10: 1-20.)

When Jesus travels, it is not just with the Twelve, but with a larger crowd (who are also called disciples), somewhere between casual supporters and his inner circle. These include some wealthy women-- an ex-prostitute Mary Magdalene, women who have been cured by Jesus, the wife of a manager of King Herod’s household-- and they help defray expenses with their money. (Luke 8: 1-3) Even the Twelve have a treasurer: Judas Iscariot, pointing up the ambiguity of money for a movement of self-chosen poverty.

With big crowds to take care of, Jesus expands his logistics staff to 70. (Luke 10:1-16) He concerns himself about whose house they will eat in. Jesus accepts all invitations, even from his enemies the Pharisees; he especially seems to choose tax collectors, since they are both rich and hospitable and recognize their own need of salvation. It is the size of his peripatetic crowds that bring about the need for multiplying loaves and fishes and turning water into wine. Jesus’ crowds are not static, but growing, and this is part of their energy and excitement.

The inner circle is not just his trusted staff.

It is also his backstage, where he can speak more intimately and discuss his concerns and plans.

“Who do people say I am?” Jesus asks the Twelve, when the movement is taking off. They replied, “Some say John the Baptist; others say Elijah; and still others, one of the prophets.”

“But what do you say?” Jesus asked. “Who do you say I am?” Peter answered, “You are the Messiah.” Jesus warned them not to tell anyone. Jesus goes on to tell them that the Son of Man will be rejected by the chief priests, that he must be killed and rise again in three days. Peter took him aside and began to rebuke him. Jesus turned and looked at the rest of the disciples. “Get thee behind me, Satan!” he said. “Your mind is not on the concerns of God, but merely human concerns.” (Mark 8: 27-33; Matthew 16: 13-23)

There is a certain amount of jostling over who are the greatest of the disciples, the ones closest to Jesus. Jesus always rebukes this; there is to be no intimate backstage behind the privacy shared by the Twelve. Jesus’ charisma is not a show put on for the crowds with the help of his staff; he is charismatic all the time, in the backstage as well. Jesus loves and is loved, but he has no special friends. No one understands what he is really doing until after he is dead.

Jesus is famous for speaking in parables. Especially when referring to himself, he uses figurative expressions, such as "the bread of life," "the light of the world," "the shepherd and his sheep." The parables mark a clear dividing line.

He uses parables when he is speaking to the crowds, and especially to potential enemies such as the Pharisees. Their meaning, apparently, did not easily come through; but audiences are generally impressed by them-- amazed and struck speechless, among other reasons because they exemplify the clever style of talking that deflects questions in unexpected directions. “Whoever has ears to hear, let them hear!” Jesus proclaims. (Mark 4: 9)

His Twelve disciples are not much better at deciphering parables, at least in the earlier part of his mission; but Jesus treats them differently. It is in private among the Twelve that he explains the meaning of parables in ordinary language, telling “the secret of the kingdom of God” (Mark 4: 10-34; Matthew 13: 34-52; Luke 8: 4-18) They are the privileged in-group, and they know it. Jesus admonishes them from time to time about their pride; but he needs them, too. It is another reason why living with Jesus is bracing. There is an additional circuit of charismatic energy in the inner circle.

But it is the crowds that feed the core of the mission, the preaching and the miraculous signs. As his movement marches on Jerusalem, opposition mobilizes. Now Jesus begins to face crowds that are divided or hostile.

The crowd begins to accuse him: “You are demon-possessed.” Jesus shoots back: “Stop judging by appearances, but instead judge correctly.” Some of the people of Jerusalem began to ask each other, “Isn’t this the man they are trying to kill? Here he is speaking publically, and they are not saying a word to him. Have the authorities really concluded he is the Messiah? But we know where this man is from; when the Messiah comes no one will know where he is from.” Jesus cried out, “Yes, you know me, and you know where I am from. I am not here on my own authority, but he who sent me is true. You do not know him, but I know him because I am from him and he sent me.”

At this they tried to seize him, but no one laid a hand on him... Still, many in the crowd believed in him. (John 7: 14-31)

Another encounter: Those who heard his words were again divided. Many of them said, “He is demon-possessed and raving mad. Why listen to him?” But others said: “These are not the sayings of a man possessed by a demon. Can a demon open the eyes of the blind?” (John 10: 19-21)

The struggle shifts to new ground. The festival crowd gathered around him, saying, “How long will you keep us in suspense? If you are the Messiah, tell us plainly.”

Jesus answered, “I did tell you, but you did not believe. The works I do in my Father’s name testify about me, but you do not believe because you are not my sheep. My sheep listen to my voice; I know them, and they follow me. I give them eternal life, and they shall never perish... My Father, who has given them to me, is greater than all; no one can snatch them out of my Father’s hand. I and the Father are one.”

Again his opponents picked up stones to stone him, but Jesus said to them, “I have shown you many good works from the Father. For which of these do you stone me?” “We are not stoning you for any good work,” they replied, “but for blasphemy, because you, a mere man, claim to be God.” Jesus answered them, “...Why do you accuse me of blasphemy because I said, ‘I am God’s Son’? Do not believe me unless I do the works of my Father. But if I do them, even though you do not believe me, believe the works, that you may understand that the Father is in me, and I in the Father.” Again they tried to seize him, but he escaped their grasp. (John 10: 24-42)

Jesus can still arouse this crowd, but he cannot silence it. He does not back off, but becomes increasingly explicit. The metaphors he does use are not effective. His sheep that he refers to means his own crowd of loyal followers, and Jesus declares he has given them eternal life-- but not to this hostile crowd of unbelievers. Words no longer convince; the sides declaim stridently against each other. The eloquent phrases of earlier preaching have fallen into cacophony. Nevertheless Jesus still escapes violence. The crowd is never strong enough to dominate him. Only the organized authorities can take him, and that he does not evade.

(6) Jesus’ down moments

Most of the challenges to Jesus’ charisma happen during the showdown in Jerusalem. A revealing occasion happens early, when Jesus visits his hometown Nazareth and preaches in the synagogue. First the crowd is amazed, but then they start to question: Isn’t this the carpenter’s son? Aren’t his mother and brothers and sisters among us? Where did he get these powers he has been displaying in neighbouring towns? When Jesus reads the scroll and says, “Today the scripture is fulfilled in your hearing,” they begin to argue. Jesus retorts: “No prophet is honored in his home town,” and quotes examples of how historic prophets were rejected. The people in the synagogue are furious.

They take him to the edge of town and try to throw him off the brow of a cliff. “But he walked right through the crowd and went his way.” (Luke 4: 14-30; Matthew 13: 53-58) Even here, Jesus can handle hostile crowds.

Including this incident of failure gives confidence in the narrative.

Another personal challenge comes when he performs one of his most famous miracles, bringing back Lazarus from the dead.

Jesus' relationship with Lazarus is described as especially close. He is the brother of the two sisters, Mary and Martha, whose house Jesus liked to stay in; and Lazarus is referred to as "the one you (Jesus) love." Jesus had been staying at their house a few miles outside Jerusalem, a haven at the time when his conflict with the high priests at the temple was escalating. When the message came that Lazarus was sick, Jesus was traveling away from trouble; although his disciples reminded him that the Jerusalem crowd had tried to stone him, he decided to go back. Yet he delayed two days before returning-- apparently planning to wait until Lazarus dies and then perform the miracle of resurrecting him. First he says to his disciples, "Our friend Lazarus has fallen asleep, but I am going to wake him up." When this figure of speech is taken literally, he tells them plainly, "Lazarus is dead, and for your sake I am glad I was not there, so that you may believe."

When he arrives back in Bethany, Lazarus had been dead for four days.

A crowd has come to comfort the sisters. Why were they so popular? No doubt their house was strongly identified with the Jesus movement; and thus there is a big crowd present, as always, when Jesus performs a healing miracle.

But this is the public aspect. For the personal aspect: Each of the two sisters separately comes to meet Jesus, and each says, "If you had been here, my brother would not have died." After Mary, the second sister, says this, Jesus sees her weeping and the crowd who had come with her also weeping, he is deeply moved. (The King James translation says, "groaning in himself.") "Where have you laid him?" Jesus says. "Come and see," she answers. Then Jesus wept.

They come to the tomb; Jesus has them roll away the stone from the entrance. Again deeply moved, Jesus calls out in a loud voice, "Lazarus, come out!"

For some time afterwards, people come to Bethany to see Lazarus, the man who had been raised from the dead. (John 11: 1-46)

Leaving aside the miracle itself and its symbolism, one thing we see in this episode is Jesus conflicted between his mission-- to demonstrate the power of resurrection-- and his personal feelings for Lazarus and his sisters. Jesus let Lazarus die, by staying away during his sickness, in order to make this demonstration, but in doing so he caused grief to those he loved. The moment when he confronts their pain (amplified by the weeping of the crowd), Jesus himself weeps. It is the only time in the texts when he weeps. It is a glimpse of himself as a human being, as well as a man on a mission.

Jesus’ next moment of human weakness comes in the garden at Gethsemane.

“Being in anguish, he prayed more earnestly, and his sweat was like drops of blood falling to the ground.” Though he left his disciples nearby with instructions to “pray that you will not fall into temptation,” they all fell asleep, exhausted from sorrow. Jesus complains to Peter, “Couldn’t you keep watch with me for one hour?” But he adds, “The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak.” But their eyes were heavy, and they did not know what to say to him. (Luke 22: 39-46; Mark 14: 32-42; Matthew 26: 36-46) Everybody’s emotional energy is down.

Particularly personal is the passage when Jesus on the cross sees his mother standing below, “and the disciple whom he loved standing near by. Jesus said to her: ‘Woman, here is your son,” and to the disciple, ‘Here is your mother.’ From that time on, the disciple took her into his house.” (John 19: 25-27)

What is so telling about this is the contrast to an event during Jesus’ early preaching in Galilee, when his mother and siblings try to make their way to him through a crowd of followers. Someone announces, “Your mother and your brothers are outside waiting to see you.” Jesus looks at those seated in a circle around him and says: “Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does God’s will is my brother and sister and mother.” (Luke 8: 19-21; Mark 3: 31-35) But on the cross he is not only thinking of fulfilling scripture, but of his own lifetime relationships.

Pierced by pain, he cries out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” “And with a loud cry, Jesus breathed his last.” (Mark 15: 21-41; Matthew 27: 30-55)

Ancient myths of dying and annually resurrecting nature-gods are not described like this-- i.e. humanly; nor are the heroic deaths of Plutarch’s noble Greeks and Romans.

Other than in the anxious hours of waiting at Gethsemane, and the torture of the crucifixion, Jesus confronting his accusers is in form and on message.

When the high priests and temple guards approach to arrest him, Jesus calmly asks who they want. “Jesus of Nazareth,” they reply. When he says, “I am he,” they shrink back. Jesus takes the initiative: “If you are looking for me, let these men go.” When they seize Jesus, one of his followers draws a sword and cuts off the ear of a priest’s servant. “Put away your sword!” Jesus says to him, “for all who live by the sword will die by the sword.” To the hostile crowd, he says, “Am I leading a rebellion, that you have come with swords and clubs to capture me? Every day I sat in the temple courts teaching, and you did not dare to arrest me. But this is your hour.” (Matthew 26: 47-56; Luke 22: 47-55; John 18: 1-12)

Then all his disciples deserted him and fled. Peter, the boldest of them, followed at a distance to the outer courtyards when Jesus was being interrogated within.

But Peter too is intimidated when servants question whether he isn’t one of Jesus’ followers. Peter denying Jesus shows how Jesus’ own crowd has been dispersed, broken up and unable to assemble, and in the face of a hostile crowd lose their faith.

Strength is in the crowd, and now the opposing crowd holds the attention space.

But indoors, in a smaller setting of rival authorities, Jesus holds his own. Before the assembly of the high priests, Jesus wins the verbal sparring, if not the verdict. Many hostile witnesses testify, but their statements do not agree. The priests try to get Jesus to implicate himself, but he keeps a long silence, and then says: “I said nothing secret. Why question me? Ask those who heard me.”

When Jesus said this, an official slapped him in the face. “Is this the way you answer the high priest?” Jesus replied, “If what I said is wrong, testify as to what is wrong. If I spoke the truth, why do you strike me?” The chief priest asks him bluntly: “Tell us if you are the Messiah, the Son of God.” “You have said so,” Jesus replies. (Mark 14: 53-65; Matthew 26: 57-63; John 18: 19-24)

Finally Jesus is taken before Pilate, the Roman governor. Jesus gives his usual sharp replies, and indeed wins him over. “Are you the King of the Jews?” Pilate asks. “Is that your own idea,” Jesus asks in return, “or did others talk to you about me?” Pilate: “Your own people and chief priests have handed you over to me. What is it you have done?” Jesus said: “My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would prevent my arrest.” “You are a king, then!” said Pilate. Jesus answered: “You say I am a king. In fact, I came into the world to testify to the truth. Everyone on the side of truth listens to me.”

“What is truth?” Pilate replied, and breaks off before an answer. (Mark 15: 1-5; Matthew 27: 11-26; John 18: 24-40)

And he goes to the crowd gathered outside the palace to say he has found no basis for a charge against Jesus. Pilate tries to set him free on a legal loophole but gives in to the crowd demanding crucifixion. After Jesus dies, Pilate gives permission for a sympathizer to take the body away instead of leaving it for ignominious disposal. Pilate’s style of behavior, too, comes across the centuries as real.

In the crises, Jesus’ interactional style remains much the same as always; but the speaking in parables and figurative language has given way to blunt explanations. Parables are for audiences who want to understand. Facing open adversaries, Jesus turns to plain arguments.

Charisma, above all, is the power to make crowds resonate with oneself. Does that mean charisma vanishes when the power over crowds goes away?*

But that would mean charisma would not be a force in drawn-out conflicts; more useful to say that charisma has its home base, its center in enthusiastic crowds, even when the charismatic leader is sometimes cut off from base.

*Historical examples include the public popularity of Gorbachev rocketing like fireworks in the middle of the 1980s in a movement for Soviet reform, but dissipating rapidly in 1991 when he is overtaken by political events and shunted aside. Jesus is a stronger version of charisma that survives adversity.

More on this in a future Sociological Eye post on theory of charisma.

Charisma is a fragile mode of organization because it depends on enthusiastic crowds repeatedly assembling. Its nemesis is more permanent organization, whether based on family and patronage networks, or on bureaucracy. Jesus loses the political showdown because the authorities intimidate his followers from assembling, and then strike at him with a combination of their organized power of temple and state, bolstered by mobilizing an excited crowd of their own chanting for Jesus’ execution. But even at his crucifixion, Jesus wins over some individual Roman soldiers (Luke 23: 47; Matthew 27: 54), although that is not enough to buck the military chain of command. This tells us that the charismatic leader relates to the crowd by personally communicating with individuals in the crowd, a multiplication of one-to-one relationships from the center to many audience-members. But charismatic communication cannot overcome a formal, hierarchic organization where individuals follow orders irrespective of how they personally feel.**

**The “cast the first stone” incident shows, in contrast, how a charismatic leader takes apart a hostile crowd by forcing its members to consult their own consciences.

As we have seen, Jesus can handle hostile questioning from crowds in the temple courts, even if opponents have been planted there by an enemy hierarchy. It is not the crowd calling for crucifixion that overpowers Jesus, but the persistent opposition of the priestly administration. Sociologically, the difference is between charismatic experience in the here-and-now of the crowd, and the long-distance coordination of an organization that operates beyond the immediate situation.

(7) Victory through suffering, transformation through altruism

When Jesus is arrested in the garden at Gethsemane, he tells his militant defenders not to resist. “Do you think I cannot call my Father, who will send twelve legions of angels? But how would the scriptures be fulfilled that say it must happen in this way?” (Matthew 26: 47-56) Jesus does not aim to be just a miracle worker; he is out to transform religion entirely.

Miracles, acts of faith and power in the emotionally galvanized crowd, are ephemeral episodes. As Jesus goes along, his miracles become parables of his mission. He heals the sick, gives the disabled new life, stills the demonic howling of people in anguish. He lives in a world that is both highly stratified and callous. The rich are arrogant and righteous in their ritual correctness-- a Durkheimian elite at the center of prestigious ceremonials. They observe the taboos, and view the penurious (and therefore dirty) underclass not just with contempt but as sources of pollution. Jesus leads a revolution, not in politics, but in morals. From the beginning, he preaches among the poor and disabled, and stirs them with a new source of emotional energy. Towards the rich and ritually dominant, he directs the main thrust of his call for repentance-- it is their attitude towards the wretched of the earth that needs to be reformed. The Jesus movement is the awakening of altruistic conscience.*

*It does not start with Jesus. John the Baptist also preaches the main points, concern for the poor, against the arrogance of the rich. Earlier, Jewish prophets like Isaiah and Amos had railed against injustice to the poor. Around Jesus' time, there may have been inklings of altruism in the Mediterranean world but if so they had little publicity or organization. Greek and Roman religious cults and public largesse were directed to the elite, or at most to the politically active class, and do not strike a note of altruism towards the truly needy. Ritual sacrifices of children for military victory carried out by the Carthaginians took place in a moral universe unimaginable to modern people. Middle-Eastern kingship was even more rank-conscious and ostentatiously cruel. See my post, “Really Bad Family Values” The Sociological Eye, March 2014.

The moral revolution has three dimensions: altruism; monastic austerity; and martyrdom.

Altruism becomes an end in itself, and the highest value. Giving up riches and helping the poor and disabled is not just aimed at improving material conditions for everyone. It is not a worldly revolution, not a populist uprising, but making human sympathy the moral ideal. Blessed are the poor, the mourning, the humble, Jesus preaches, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. (Luke 6: 17-23) Altruism comes on the scene historically as the pathway to otherworldly salvation. ** What is important for human lives is the change in the moral ideal: it not only gives hope to the suffering but calls the elite to judge themselves by their altruism and not by their arrogance.

**The mystery cults of the Hellenistic world (Orphics, Hermeticists, Neo-Pythagoreans and Neo-Platonists, various kinds of Gnostics etc.) had the idea of otherworldly salvation, but not the morality of altruism. Their salvation was purely selfish and their pathways merely secret rituals and symbols. They were still on the ancient side of the revolution of conscience.

The movement is under way at least a little before Jesus launches his mission at age 30.

John the Baptist preached repentance before the coming wrath. “What should we do?” the crowd asked. John answered, “Anyone who has two shirts should share with one who has none, and anyone who has food should do the same.” Even tax collectors came to be baptized. “Teacher,” they said, “what should we do?” John replied, “Don’t collect any more than you are required to.” Soldiers asked him, “And what should we do?”

He replied, “Don’t extort money and don’t accuse people falsely-- be content with your pay.” (Luke 3: 1-14) Repentant sinners were baptized in the river.

To the Pharisees and Sadducees-- who will not repent and be baptized-- John thunders, “You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the coming wrath?”

Later, when John’s disciples come to visit Jesus’ disciples, Jesus speaks to the crowd about John: “What did you go out into the wilderness to see? ... A man dressed in fine clothes? No, those who wear expensive clothes and indulge in luxury are in palaces. But what did you go out to see? A prophet? Yes, and more than a prophet.” Jesus goes on to compare his mission to John’s.

“John the Baptist came neither eating bread nor drinking wine, and you say, ‘He has a demon.’ The Son of Man came eating and drinking, and you say, ‘Here is a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners. But wisdom is proved right by all her children.” (Luke 7: 18-35)

Jesus not only amplifies John’s mission, he also moves into another niche: not the extreme asceticism of the desert, but among the lower and middle classes of the towns and villages.

Monastic austerity.

Jesus’ disciples give up all property, becoming (as John the Baptist did *) the poorest of the poor. But they are not as the ordinary poor and disabled. They retain their health, and have an abundance of the richness of spirit, what they call faith-- i.e. emotional energy.

Committed disciples who have left family, home and occupation, rely on the enthusiasm of a growing social movement to provide them with daily sustenance. They live at the core of the movement. Since this location is the prime source of emotional energy, there is an additional sense in which living by faith alone is powerful.

*Matthew 3: 1-8 stresses John’s asceticism, a wild man living in the wilderness on locusts and honey, dressed in clothes of camel’s hair.

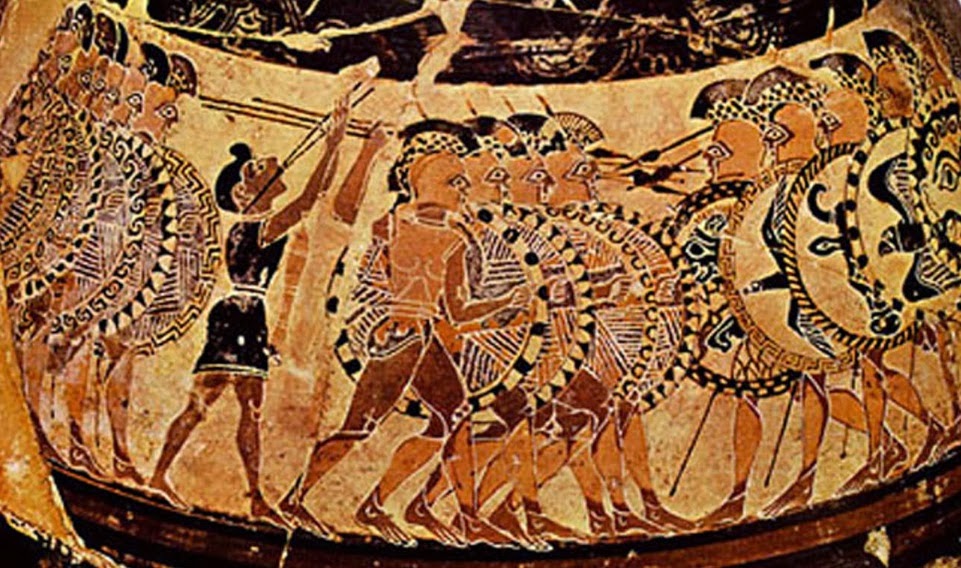

Later this arrangement became institutionalized as the relationship between monks and lay people.** During the missionary expansion of Christianity, monks were the pioneers, winning converts and patrons on the pagan frontiers through personal impressiveness-- their institutionalized charisma, which is to say Christian techniques of disciplined austerity generating emotional strength. Still later, movements like the Franciscans, deliberately giving up monastic seclusion to wander in the ordinary world among the poor and disabled, combine austerity with a renewed spirit of altruism and thereby create the idealistic social movement. Altruistic movements first used modern political tactics for influencing the state in the late 1700s anti-slavery movement, but the lineage builds on the moral consciousness and social techniques that are first visible with the Jesus movement.

**There were precedents of monasticism in the 300s BC such as the Cynics, who lived in ostentatious austerity--- such as Diogenes living in a barrel. Cynics denounced the pitfalls and hypocrisy of seeking riches and power, but they lacked any concern for the poor and did not advocate altruism.

Martyrdom.

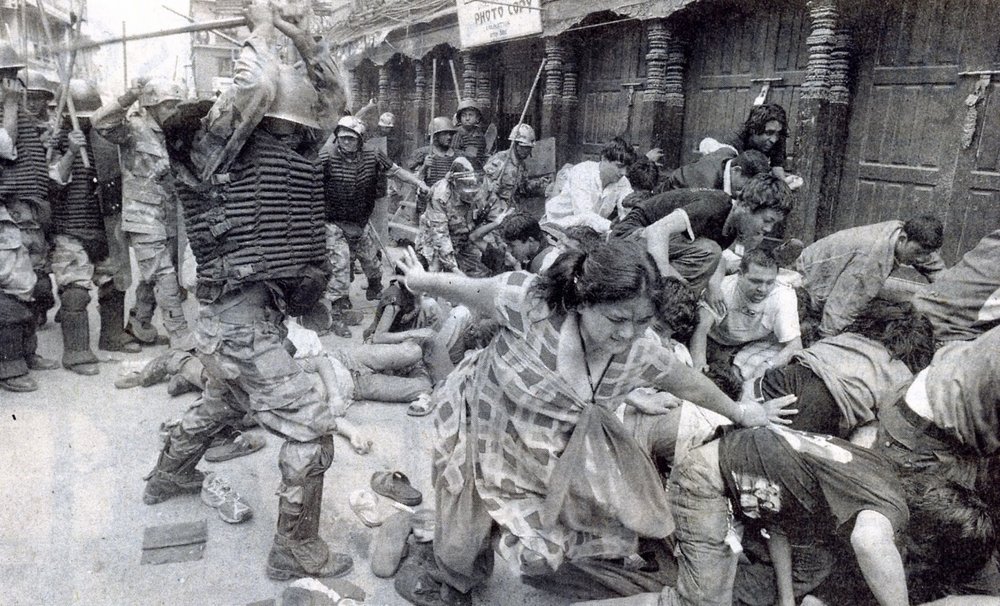

The crucifixion of Jesus becomes, not the end of the movement, but its rallying point. The cross becomes the symbol of its members, and a source of personal inspiration for individuals in times of suffering and defeat. We are so used to this symbol that the enormity of the shift is lost on us. Crucifixion, which existed for several hundred years previously in the authoritarian kingdoms of the Middle East before spreading to Rome, was an instrument of death by slow torture, a visible threat of state terrorism. When the Sparticist revolt of gladiators was put down in 71 BC, the Romans crucified captured gladiators for hundred of miles along the roads of southern Italy. To turn the cross into a symbol of a movement, and of its triumph, was a blatant in-your-face gesture of the moral revolution: we cannot be beaten by physical coercion, by pain and suffering, it says; we have transformed them into our strength. Martyrs succeed when they generate movements; and are energized by the emotional solidarity of standing together in a conflict, even in defeats.

That is why ancient cultural precedents of fertility gods who die by dismemberment but are resurrected like the coming of the crops in the following year do not contain the social innovation of Christianity.

Fertility gods may be depicted as suffering but their message is not moral strength, and their cult concerns recurring events in the material world, not otherworldly salvation.**

**Euripides is the nearest to an altruistic liberal in the Greek world; but his play The Bacchae-- depicting an actual contemporary movement of frenzied dancers that challenged older Greek religious cults-- breathes an atmosphere of ferocious violence and revenge, the polar opposite of the Christian message of forgiveness and charity. Euripides’ plays focus the audience’s sympathy on the sufferings of individual characters, but these are members of elite families who suffer in from shifting fortunes of the upper classes. There is not even a glance at the poor.

Martyrdom also becomes institutionalized in the repertoire of religious movements. In its early centuries, Christianity grows above all by spectacular and well-publicized martyrdom of its hero-leaders. (There is also a quieter form of conversion through networks attracted to its moral style, its care for the sick, and its organizational strength. Stark, The Rise of Christianity).

Martyrdom becomes a technique for protest movements, and movement-building.

“What does not kill me, makes me stronger,” Nietzsche was to write. Ironically: for all his attacks on the moral revolution of Christianity, this is a Christian discovery he is citing. Religious techniques set precedents for modern secular politics. Protest movements win by attracting widespread sympathy for their public sufferings, turning the moral tables on those who use superior force against them. This too is world-changing. It is little exaggeration to say that the moral forces of the modern world were first visible in the Jesus movement.

Appendix.

The Social Context of Miracles.

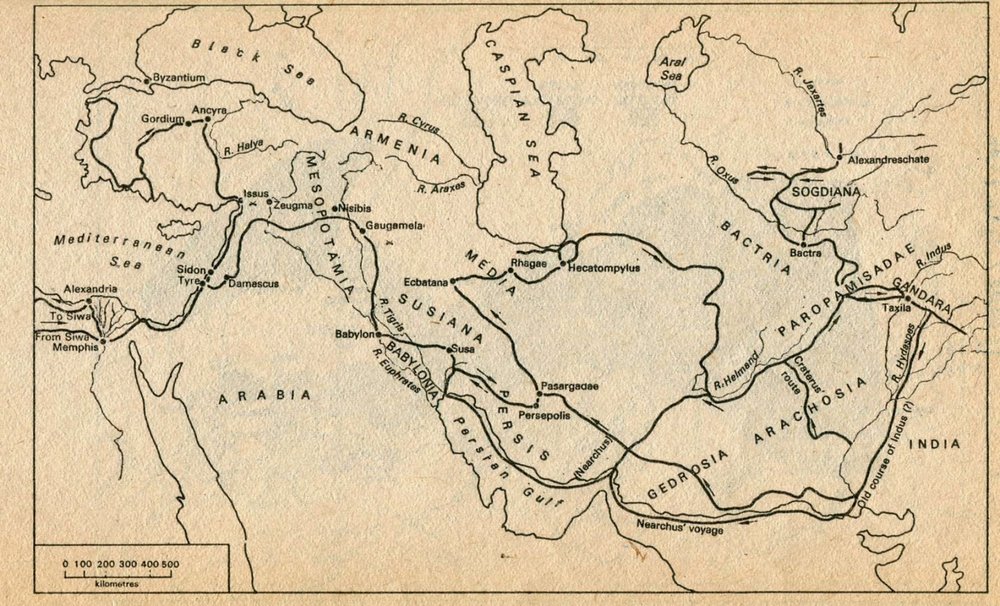

Some modern people think that Jesus never existed, or that the stories about him are myths. The details of how Jesus interacted with people in the situations of everyday life consistently show a distinctive personality. All texts about the ancient past are subject to distortion and mythologizing tendencies; but an objective scholar, with no axe to grind one way or the other, would conclude that what we read of Jesus is as valid as what Plutarch summarizes from prior sources about Alexander or Pericles, or what other classical writers reported about exemplary heroes. The gospels have an advantage of being written closer to the lifetime of their subject, and possibly by several of Jesus’ close associates.

What about the miracles? I will focus on what a micro-sociologist can see in the details of social interaction, especially what happens before and after a miracle. I will examine only those miracles that are described as happening in a specific situation, a time and place with particular people present. Summaries of miracles by Jesus and his disciples do not give enough detail to analyze them, although they give a sense of what kinds of miracles were most frequent.

Let us go back to a question that has been hanging since I have discussed the beginning of Jesus’ ministry. Jesus attracts big crowds, by his preaching and by his miracles. He preaches an overthrow of the old ritualism; an ethic of humility and altruism for the poor and disabled; and the coming of the true kingdom of God, so different from this rank-conscious world. He also performs miracles, chiefly medical cures through faith-healing; casting out demons from persons who are possessed; and bringing back a few people from the cusp of death. There are also some nature miracles and some apparitions, although these should be considered separately because they almost never occur among crowds.

The roster of miracles described in detail include:

22 healing miracles, all happening in big crowds;

3 logistics miracles, where Jesus provides food or drink for big crowds;

5 nature miracles, all happening when Jesus is alone with his inner Twelve disciples, or some of them;

2 apparitions: 1 with 3 close disciples; 1 in a crowd.

So is Jesus chiefly a magician? And as such, are we in the realm of wonders, or superstition, or sleight of hand tricks? I will confine the discussion to some sociological observations.

Which comes first, the preaching or the miracles? The gospels are not strictly chronological, and sequences vary among them, but clearly there are a lot of miracles early on, and this is one of the things that attracts excited crowds to Jesus. People bring with them the sick, the lame, blind, and others of the helpless and pathetic. This is itself is a sign of incipient altruism, since on the whole ancient people were quite callous, engaging in deliberately cruel punishments, routinely violent atrocities, and a propensity to shun the unfortunate rather than help them. Jesus’ emphasis upon the lowly of the earth meshes with his medical miracles; they are living signs of what he is preaching in a more ethical sense.

Jesus’ healing miracles always happen in the presence of crowds. If that is so, how did the first miracles happen? What brought the first crowds together must have been Jesus’ preaching. This is particularly likely since John the Baptist was attracting large crowds, and had his own movement of followers. John did not perform medical miracles or any other kind, and he preached the same kind of themes as Jesus at the outset: humility and the poor; repentance; the coming kingdom of God, except that John explicitly said someone else was coming to lead it.

The plausible sequence is that Jesus attracted crowds by his preaching, and it was in the midst of the crowds’ enthusiasm-- their faith-- that the healing miracles take place.* That miracles depend on faith of the crowd is underscored by Jesus’ failure in Nazareth, his home town. “And he did not do many miracles there because of their lack of faith.” (Luke 4: 14-30; Matthew 13: 53-58)

*Origins of the word enthusiasm are from Greek enthous, possessed by a god, theos.

Jesus’ healing miracles divide into: 4 cures of fever and other unspecified sickness; 9 events where he cures long-term disabilities (3 with palsy/paralysis, crippled, or shriveled hand; 2 blind, 1 deaf/mute; 1 with abnormal swelling; 1 leper, and later a group of 10 lepers); 6 persons possessed with demons; 3 persons brought back from death. The various types may overlap.

The 3 who are brought back from death include the 12-year-old daughter a rich man whom he thinks is dead, but Jesus tells him she is not dead, but asleep (Luke 8: 41-42,49-56); a widow’s son who is on his funeral bier, i.e. recently pronounced dead (Luke 7: 11-17); and finally Lazarus (John 11: 1-46).

Their illnesses are not described, but could have been like the cases of fever in Jesus' other miracles.

The disabilities that Jesus cured also overlap with the persons described as possessed by demons: one is “robbed of speech” and foams at the mouth (Mark 9: 14-29; Matthew 17: 14-21; Luke 9: 37-43); another has a mute demon and is also blind (Luke 11: 14-28; Mark 9: 32-34; Matthew 12: 22-37); another is vaguely described as a woman’s daughter possessed by an unclean spirit (Mark 7: 24-30; Matthew 14: 21-28).

At least one of these appears to have epileptic fits.

Another is a naked man who sleeps in tombs, and has been chained up but breaks his chains (Luke 8: 26-39; Mark 5: 1-20; Matthew 8: 28-34). Casting out demons appears to be one of the most frequent things Jesus does, mentioned several times in summaries of his travels “preaching in synagogues and casting out demons” (Mark 1: 39) “many who were demon-possessed were brought to him” (Matthew 8: 16). This is a spiritual power that can be delegated; when his disciples are sent out on their own they come back and report “even the demons submit to us in your name.” (Luke 10: 17; Matthew 10: 1).**

One of his most fervent followers, Mary Magdalene, is described of having 7 demons cast out (Luke 8: 2); possibly this means she went through the process 7 times. She is also described as a prostitute, one of the outcasts Jesus saves; we might think of her as having gone through several relapses, or seeking the experience repeatedly (much like many Americans who undergo the “born again” experience more than once).

**Sometimes the disciples fail in casting out a demon. In one case, the boy’s father says the spirit throws him to the ground, where he becomes rigid and foams at the mouth. When Jesus approaches, the boy goes into convulsions. The father says to Jesus, “If you can, take pity on us and help us.” Jesus replies: " 'If you can’? All things are possible for one who believes." Immediately the boy’s father exclaimed: “I do believe; help me overcome my unbelief.” When Jesus saw a crowd running to the scene, he commanded the spirit to leave the boy and never enter again. The spirit shrieked and convulsed him violently. the boy looked so much like a corpse that many said, “He is dead.” But Jesus took his hand and lifted him to his feet, and he stood up. (Similar to raising from the dead.) After Jesus had gone indoors, his disciples asked him privately, “Why couldn’t we drive it out?” Jesus replied, “This kind can come out only by prayer.” (Mark 9: 14-29) Jesus recognizes different kinds of cases and has more subtle techniques than his disciples.

What does it mean to be possessed by a demon? A common denominator is some serious defect in the social act of speaking: either persons who shout uncontrollably and in inappropriate situations (like the man who shouts at Jesus in a synagogue, “What do you want with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are-- the Holy One of God!” (Mark 1: 21-28); or who are silent and will not speak at all.

We could diagnose them today as having a physiological defect, or as mentally ill, psychotic, possibly schizophrenic.

But in ancient society, there was no sharp distinction between sickness and mental illness. There were virtually no medical cures for sicknesses, and religious traditions regarded them as punishments from God or the pagan gods; seriously ill persons were left in temples and shrines, or shunted onto the margins of habitation. Left without care, without human sympathy, virtually without means of staying alive, they were true outcastes of society.

Here we can apply modern sociology of mental illness, and of physical sickness. As Talcott Parsons pointed out, there is a sick role that patients are expected to play; it is one’s duty to submit oneself to treatment, to put up with hospitals, follow the authority of medical personnel, all premised on a social compact that this is done to make one well. But ancient society had no such sick role; it was a passive and largely hopeless position. Goffman, by doing fieldwork inside a mental hospital, concluded that the authoritarian and dehumanizing aspects of this total institution destroys what sense of personal autonomy the mental patient has left. Hence acting out-- shouting, defecating in the wrong places, showing no modesty with one’s clothes, breaking the taboos of ordinary social life-- are ways of rebelling against the system. They are so deprived of normal social respect that the only things they can do to command attention are acts that degrade them still further. Demon-possessed persons in the Bible act like Goffman’s mental patients, shouting or staying mute, and disrupting normal social scenes.*

*This research was in the 1950s and 1960s, before mental patients were controlled by mood-altering drugs. The further back we go in the history of mental illness, the more treatments resemble ancient practices of chaining, jailing or expelling persons who break taboos.

One gets the impression of a remarkable number of such demon-possessed-- i.e. acting-out persons-- in ancient Palestine.** They are found in almost every village and social gathering. Many of them are curable, by someone with Jesus’ charismatic techniques of interaction. He pays attention to them, focusing on them wholly and steadily until they change their behavior and come back into normal human interaction; in every case that is described, Jesus is the first person in normal society with whom the bond is established. Each acknowledges him as their savior and want to stay with him; but Jesus almost always sends them back, presumably into the community of Christian followers who will now take such cured persons as emblems of the miracles performed.

**A psychiatric survey of people living in New York City in the 1950s found that over 20% of the population had severe mental illness. (Srole 1962) It is likely that in ancient times, when stresses were greater, rates were even higher.

Notice that no one denies the existence of demons, or denies that Jesus casts them out. When Jesus meets opposition (John 10: 19-21; Luke 11: 14-20) the language of demons is turned against him. Jesus himself, like those who speak in an unfamiliar or unwelcome voice, is accused of being demon-possessed. The same charge was made against John the Baptist, who resembled some demon-possessed persons by living almost as a wild man in the wilderness. The difference, of course, is that John and Jesus can surround themselves by supportive crowds, instead of being shunned by them.

Similarly, no one denies Jesus’ medical miracles. The worst that his enemies, the religious law teachers and high priests, can accuse him of is the ritual violation of performing his cures on the Sabbath. This leads to Jesus’ early confrontations with authority; he can point to his miracles to forcefully attack the elite as hypocrites, concerned only with their own ritually proper status but devoid of human sympathy.

Jesus’ miracles are not unprecedented, in the view of the people around him; similar wonders are believed to have taken place in the past; and other textual sources on Hellenistic society refer to persons known as curers and magicians. Jesus works in this cultural idiom. But he transforms it. He says repeatedly that it is not his power as a magician that causes the miracle, but the power of faith that people have in him and what he represents.

A Roman centurion pleads with Jesus to save his servant, sick and near death. The centurion calls him Lord and says he himself is not worthy that Jesus should come under his roof. But as a man of authority, who can order soldiers what to do, he recognizes Jesus can say the word and his servant will be healed. Jesus says to the crowd, “I have not found such great faith even in Israel.” Whereupon the servant is found cured. (Luke 7: 1-10; Mark 8: 5-13)

In the midst of a thick crowd pressing to see Jesus, he feels someone touch him-- not casually, but deliberately, seeking a cure. It is a woman who has been bleeding for 12 years.

Jesus says “I know that power has gone out from me.” The woman came trembling and fell at his feet. In the presence of the crowd, she told why she had touched him and that she was healed. Jesus said, “Daughter, your faith has healed you. Go in peace.” (Luke 8: 43-48; Mark 5: 21-43; Matthew 9: 20-22.)

While passing through Jericho, a blind man in the crowd calls out repeatedly to Jesus, although the crowd tells him to be quiet. Jesus stopped and had the man brought to him, and asked what he wanted from him. “Lord, I want to see,” he replied. Jesus said, “Receive your sight, for your faith has healed you.” (Luke 18: 35-43; Mark 10: 46-52; Matthew 20: 29-34)

Failure to produce a miracle is explained as a failure of sufficient faith. In another version of the demon-possessed boy, the disciples ask privately, “Why couldn’t we drive it out?” Jesus replied, “Because you have so little faith. If you have faith, you can move mountains. Nothing is impossible for you.” (Matthew 17: 19-20) The message is in the figurative language Jesus habitually uses, the mastery of word-play which makes him so dominant in interaction.

The faith must be provided by his followers. When asked to perform a miracle-- not because someone needs it, but as a proof of his power, a challenge to display a sign-- Jesus refuses to do it. (Luke 11: 29-32; Matthew 12: 38-39; 16: 1-4)

As Jesus’ career progresses, he becomes increasingly explicit that faith is the great end in itself. The goal of performing miracles is not to end physical pain, or to turn it into worldly success. Jesus is not a magician, or conjurer.

Magic, viewed by comparative sociology, is the use of spiritual power for worldly ends. For Jesus it is the other way around.

Healing miracles have an element of worldly altruism, since they are carried out for persons who need them; but above all those who need to be brought back into the bonds of human sympathy. Miracles are a way of constituting the community, both in the specific sense of building the movement of his followers, and in the more general sense of introducing a spirit of human sympathy throughout the world. Miracles happen in the enthusiasm of faith in the crowd, and that combination of moral and emotional experience is a foreshadowing of the kingdom of heaven, as Jesus presents it.

Jesus’ logistics miracles consisted in taking a small amount of food and multiplying it so that crowds of 5,000 and 4,000 respectively have enough to eat and many scraps left over (Luke 9: 10-17; Matthew 14: 13-21; Mark 6: 30-44; Mark 8: 1-10). It has been suggested that the initial few fishes and loaves of bread were what the crowd first volunteered for the collective pot; but when Jesus started dividing them up into equal pieces and passing them around, more and more people contributed from their private stocks. (Zeitlin) The miracle was an outpouring of public sharing. Jesus does something similar at a wedding party so crowded with guests that the wine bottles are empty. He orders them to be filled with water, whereupon the crowd becomes even more intoxicated, commenting that unlike most feasts, the best wine was saved for last (John 2: 1-11). Possibly the dregs of wine still in the casks gave some flavour, and the enthusiasm of the crowd did the rest. Party-goers will know it is better to be drunk with the spirit of the occasion than sodden with too much alcohol.

Miracles show the power of the spirit, which is the power of faith that individuals have in the charismatic leader and his intensely focused community. Such experiences is to be valued over anything in the world; it transcends the ordinary life, in the same way that religion in the full sense transcends magic.

The significance of miracles is not in a particular person who is cured, but a visible lesson in raising the wretched of the earth, and awakening altruistic conscience. After the miracle of the loaves and fishes, Jesus says to a crowd that is following him eagerly, “You are looking for me, not because you saw the signs I performed but because you ate the loaves and had your fill. Do not work for food that spoils, but for food that endures to eternal life.”

They ask him, “What sign will you give that we may see it and believe you?” Jesus answered: “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never go hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty.” He goes on to talk about eating his flesh and drinking his blood, speaking in veiled language about the coming crucifixion. It causes a crisis in his movement: “From this time many of his disciples turned back and no longer followed him.” (John 6: 22-52) Those who wanted to take miracles literally were disappointed.

Jesus’ nature miracles differ from the others in not taking place in crowds, but among his intimate disciples. Here the role of faith is highlighted but in a different sequence. Instead of faith displayed by followers in the crowd, bringing about a healing miracle, now Jesus produces miracles that have the effect of reassuring his followers.

A storm comes up while the twelve disciples are on a boat in the weather-wracked Sea of Galilee. They are afraid of drowning, but Jesus is sleeping soundly. “Oh ye of little faith, why are you so afraid?” he admonishes them, after they wake him up and the storm stills. (Matthew 8: 23-27; Mark 4: 35-41; Luke 8: 22-25)

Jesus is imperturbable, displaying a level of faith his disciples do not yet have.

In another instance, he sends his disciples out in a boat while he stays to dismiss the crowd and then to pray in solitude on the mountainside. They are dismayed while Jesus is away and the water grows rough and they cannot make headway with their oars. After a night of this, just before dawn they are frightened when they perceive him walking across the water, and some think he is a ghost.

Jesus calms them by saying, “It is I; don’t be afraid.” He enters the boat and the wind dies down, allowing them finally to make it to shore. (Mark 6: 45-52; John 6: 16-21) In one account, Peter says, “Lord if it is truly you, let me come to you on the water.” Jesus says, “Come,” and Peter begins to walk. But he becomes afraid and begins to sink. Jesus immediately catches him with his hand: “You of little faith, why did you doubt?” (Matthew 14: 22-33)

The pattern is: for his disciples, who are supposed to show a higher level of faith, Jesus performs miracles when they feel in trouble without him.*

*Other miracles on the Sea of Galilee: when Jesus recruits Simon and Andrew, first by preaching from their boat, then pushing off from shore, whereupon they make a huge catch of fish. (Luke 5: 1-11); and when Jesus responds to a tax demand by telling Peter to fish in the lake, where he will catch a fish with a coin in its mouth to pay their taxes. (Matthew 17: 24-27)

At the end of the miracle of curing a demon-possessed man, Jesus sends the demons into a nearby herd of swine (presumably polluted under Jewish law), whereupon they rush madly off a cliff and drown themselves in the lake. (Luke 8: 26-39; Mark 5: 1-20; Matthew 8: 28-34) One nature miracle happens on dry land: on his way into Jerusalem to cleanse the temple he curses a fig tree which has no fruit for him and his followers; and when he returns in the evening, it has withered. (Mark 11: 15-19; Matthew 21: 18-21) The miracle is a living parable on the withered-up ritualists whom Jesus is attacking.

Apparitions, finally, are subjective experiences that particular people have at definite times and places. There is nothing sociological to question about their having such experiences, but we can notice who is present and what they did. The event called the Transfiguration happens when Jesus takes three close disciples up a mountain to pray-- a special occasion since he usually went alone. They see his face and clothes shining with light, see historic persons talking to Jesus and hear a voice from a cloud. The disciples fall on the ground terrified, until Jesus touches them and tells them not to be afraid, whereupon they see that Jesus is alone.

Jesus admonished them not to tell anyone about what they had seen. (Luke 9: 28-30; Matthew 17: 1-13; Mark 9: 2-13)

When Jesus' mission in Jerusalem is building up towards the final confrontation between his own followers and increasingly hostile authorities and their crowds. Jesus announces “the hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified.” A voice from heaven says “I have glorified it.” Some in the crowd said that it thundered, others that an angel spoke. Jesus tells them that the vision is for their benefit, not his; and that “you will have the light only a little while longer.” When he finished speaking, he hid from them. (John 12: 20-36) The crowd was not of one mind; they disagree about whether Jesus is the Messiah who will rule and remain forever, while Jesus sees the political wind blowing towards his execution. The subjective feeling of a thunderous voice in the crowd, but variously interpreted, reflects what was going on at this dramatic moment.