Networks are the actors on the stage of intellectual history. Creativity is not an attribute of individual persons standing alone. Creativity happens in chains of individuals. They pass along skills and techniques. They extend each other's work. They build on rivalries to find new niches in the attention space of the field.

In The Sociology of Philosophies, I traced the careers and networks of 3000 philosophers and mathematicians, from all the major world civilizations, from about 500 B.C. to 1950 A.D. These are my main conclusions:

Major philosophers never appear alone; there are always 2 or 3 (or slightly more) of them in the same place and the same generation.

The most important philosophers are connected to others in two dimensions: vertically across generations, from mentors to pupils or protégés; and horizontally among acquaintances, friends, and rivals. Often they begin as a small clique of rebels against the older generation, then split apart into rival positions once they achieve fame.

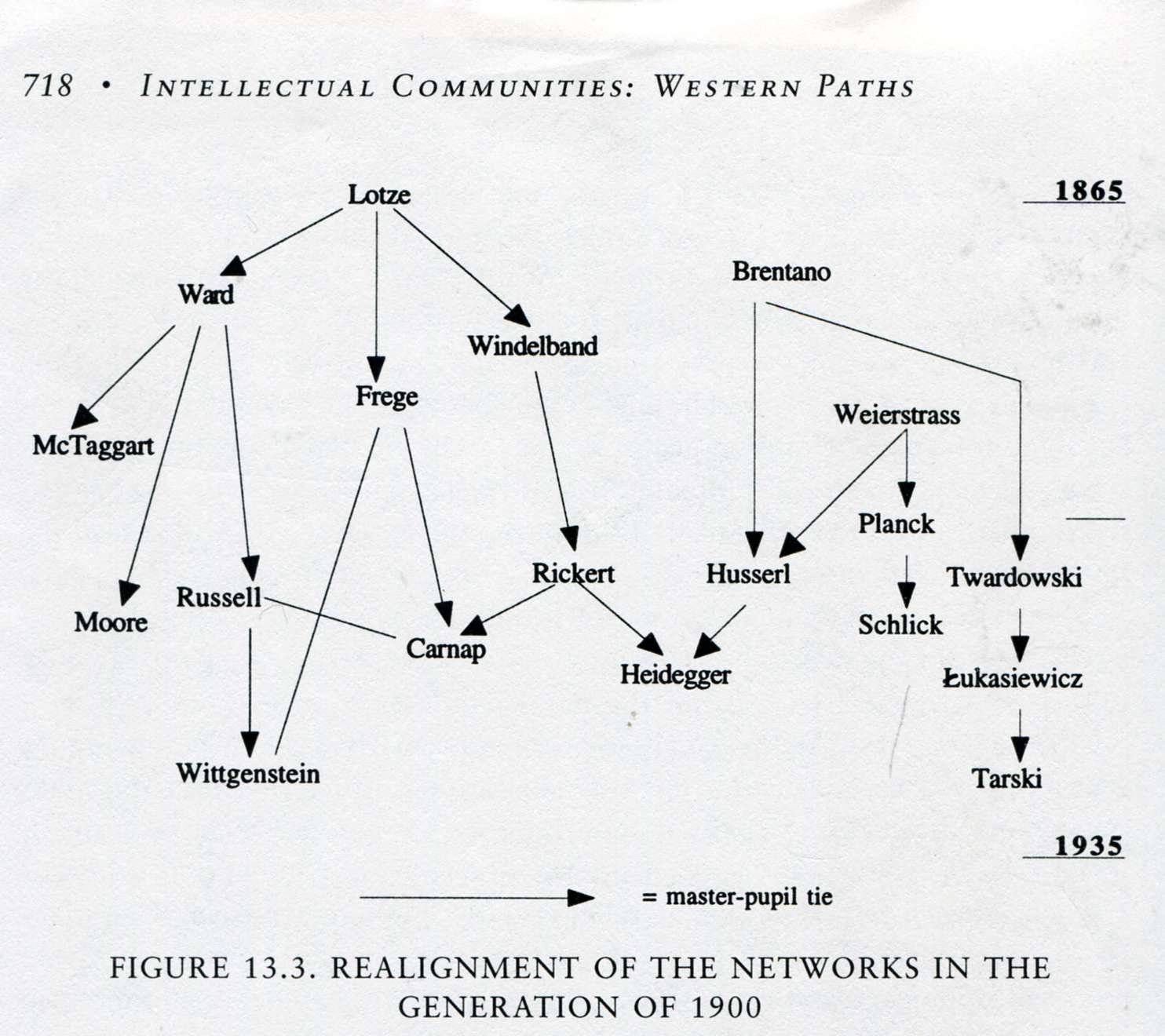

Look at the European network at the turn of the 20th century. In this simplified network, we see Wittgenstein is a pupil of both Russell and Frege (and in close contact with G.E. Moore, where he acquired an interest in ordinary language). And Wittgenstein shares the same teacher—Frege —with Carnap. Surprisingly, Carnap has a Neo-Kantian teacher in common with Heidegger, who was taught also by Husserl. Husserl in turn is only a few links from the mathematicians preceding the Vienna Circle—the two major opposing schools branch off from the same point. Wittgenstein and Heidegger are network cousins, so to speak.

What we can infer from these network patterns about the process of creativity? What is it that the younger generation learns from master-pupil chains? It cannot be simply imitation, since creativity means doing something new. Great thinkers have many pupils, but the ones who loyally repeat their teachers do not become famous in their own right. Close contact with the creators of the previous generation is the way to acquire their methods of being innovative: not so much specific ideas as their way of positioning oneself in the field so as to do something distinctive. Creativity is a process of recombining concepts to find new combinations, such as those we see in the networks around Wittgenstein, Carnap, Heidegger, and Husserl.

Newcomers who become creative internalize a sense of the field. Concepts and the persons who create them become synonymous in their minds. The sense of who are ones allies and one’s enemies becomes automatic; such persons think and create faster than others. They appear to think intuitively, but this is not a lifelong individual attribute; it arises by experience in the centers of creative networks.

The same process happens in horizontal circles of "Young Turks" rebelling together: intense discussions and arguments within the group produce a strong sense of where the action is, and what are the new niches they can create in moving beyond what has already been done. The Vienna Circle is another such example.

Do these patterns apply to all fields of creativity? Yes, with some exceptions (I find it applies to painters, but novelists are different). But this has to be shown empirically for each field. I am now applying the network method to music composers in Europe from 1600 to 1930.

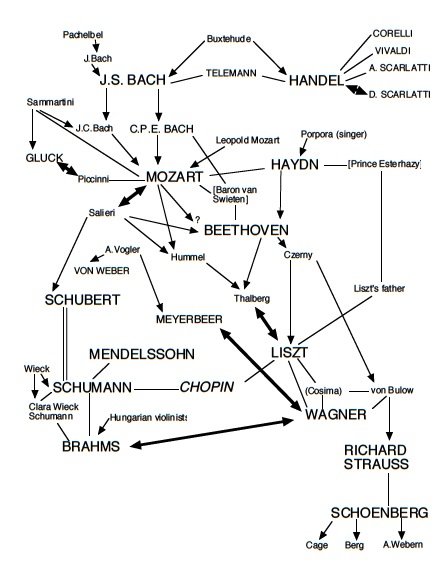

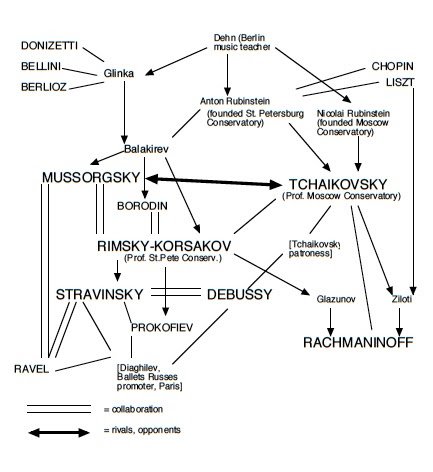

We will look at two of the networks: the German-speaking area from 1700 to 1900; and Russia from 1830-1930. There are also networks for Italy, France, and elsewhere that I will not discuss.

My method is to assemble a large number of names of musicians: those in large CAPITALS are major (such as Handel); small capitals are secondary (such as C.P.E. Bach); and small print are minor (such as Pachelbel). Rank is based on their long-term reputation, which I measure by number of performances and recordings of their music, music scores for piano, and by the amount that has been written about them.

I checked their biographies, looking for details of who they took lessons from, or worked with as an apprentice or accompanist [these are network links with an arrow]. Network lines without arrows indicate persons who are friends and acquaintances. I limit these to contacts which happen early in the younger musician’s career, preceding their major creativity. Lines with arrows at both ends indicate rivals, such as the famous rivalry between Wagner and Brahms. Links consisting of double lines indicate collaboration: these persons both worked on producing the same composition.

Look now at the German network.

The major composers are linked to each other, both vertically and horizontally. Many are direct contacts; some are mediated by secondary or minor figures in a two-link connection. Johann Sebastian Bach is connected to Mozart downstream, via of two of his sons, including the secondary figure C.P.E. Bach (who for a time was more famous than his father). Mozart and Haydn have personal contact and exchanged mutual influences. Beethoven is a pupil of Haydn and possibly of Mozart. Also very important is the mediating link, Baron van Swieten, the leading music patron in Vienna—who was the early patron of both Mozart and Beethoven. Van Swieten, who had known C.P.E. Bach in Berlin, also revived Bach's music and propagated the idea that some music is perennial classics, not just ephemeral music for the present occasion, and that some composers are living classics in our midst. Beethoven was the first to benefit from this new status; Mozart came a little too early.

Via direct or 2-link connections, we can trace the network of important composers for 8 generations, from Bach and Handel down to Schoenberg and John Cage.

Patrons are an important part of the network. Haydn began his career as accompanist to a traveling opera singer, thus learning the current repertory; he then became the house composer for the palace orchestra of Prince Esterhazy. It was just at this time when orchestras in the modern sense developed, with large number of string players and other instruments; and the time of the shift from polyphonic counterpoint (characteristic of Bach and Handel) to homophonic compositions of melody line and supporting chords. Haydn was the first to have the opportunity to experiment with the melody-and-chord style, with his own orchestra; and to lay down the chief forms of orchestral music still popular to the present time. Liszt's father was a musician in this same orchestra, and the Esterhazy family sponsored the early training of Franz Liszt, who became the first big pop star, in the era when the modern piano spread into middle-class households, resulting in a big outburst of amateur music fans.

I will note two more ways of launching a career. Schubert struggled in poverty, but (besides some lessons from Mozart's enemy, Salieri), he had the great advantage of being a choir singer in a school in Vienna that had its own student orchestra; this enabled Schubert in his teens to learn the scores of Mozart and Beethoven by conducting them. Schubert also could use this orchestra to try out symphonies of his own-- the earliest ones were imitative, but the later ones a distinctive blend of his own.

Wagner illustrates another way to acquire a network link that launches one's creative fame. His early career is in a theatre family, without direct contacts with important musicians. His early compositions are unsuccessful, until he reaches Paris around 1840, where he has contact with a conventional opera composer, Meyerbeer. More importantly, Wagner has to eke out a living working for publishers by writing out orchestra parts for opera composers like Donizetti. Wagner generates a revolution in opera by reacting against the operatic style in which the solo singer is the center and all the rest of the instruments are background-- a formula that Wagner reverses: the orchestra carries the musical themes, and the singers provide accent marks.

This is creativity by negation: Wagner reverses one central element in the traditional style, while keeping other techniques such as chordal harmonies. This is similar to the development of non-Euclidean geometries, by rejecting the parallel lines postulate, then reworking the rest of traditional geometry on that basis. It became a technique of innovation in mathematics, such as creating non-commutative algebras, and then a variety of non-Euclidean geometries once the pathway was opened. This method of axiomatizing and then reorganizing the philosophical field was taken up by Wittgenstein two generations later, after Russell and Whitehead attempted it in the foundations of mathematics.

Wagner learned his technique, and formulated his distinctive style, by several years of grinding work at the heart of the opposing camp. Knowing the techniques of your enemies in detail is the crucial resource for those who want to establish a new direction. Reading and copying music scores gives a strong sense of how existing music is put together, and how it can be done differently.

Turn now to the Russian network. The most prominent pattern is the group of "Young Turks" –the young composers who set out to create a distinctively Russian national music. They were famously called the "mighty five" or "mighty handful" because they were featured in an early concert together, but only four of them are important. Balakirev is the earliest, the first to bring European techniques of orchestral composition into Russia in the 1850s and 60s. His network comes from several Russians who had gone to Germany and France: Glinka who introduced opera into Russia, and the Rubinstein brothers who founded the music conservatories at St. Petersburg and Moscow. The network connections are to European composers Donizetti and Berlioz, on one side, and Chopin and Liszt on the other.

The great Russian composers had to learn their orchestral techniques for themselves, since none of them attended conservatories (which did not yet exist). They are all from families of rich landowners, and they attend government schools for officials and military officers. Two of the most important, Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, are the first professors of composition at the Moscow and St. Petersburg conservatories—and they got their posts before they had composed anything notable, learning on the job. Both of them published books on orchestration-- creating the lush Russian sound of full instrumentation, going beyond the string-dominated European orchestras. In effect, the Russians had a musical version of the "advantage of comparative backwardness", jumping over the forming generations of European music into the late 19th century phase when the classical melody-plus-chords formula was being transcended.

The most radical of the Russian composers, Mussorgsky, was rather like a hippie-- full of radical ideas at the time of the freeing of the serfs, living on a commune, drinking heavily. He composes a nationalist Russian opera, Boris Godunov, full of the sounds of monk's chants and booming church bells. He has trouble getting it performed; at first he does not know enough about opera to have a part for a soprano. Rimsky-Korsakov becomes a mentor to the rest of the group, helping the others with orchestration. Boris Godunov became known to the world in a posthumous version reworked by Rimsky-Korsakov, who also helped with the orchestration of Night on Bald Mountain, and Mussorgsky's unfinished opera, Khovanshchina.

The habit of collaborating and reworking each other's scores continued into the following generation. With the exception of Tchaikovsky, who I will discuss in a minute, Russian music was unknown to the world until Diaghilev produced Boris Godunov in 1907 in Paris, and the Ballets Russes between 1909 and 1913, introducing the work of Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, and above all Mussorgsky to the western world. Debussy and other modernist composers collaborated with Stravinsky in the Sacre du printemps / The Rite of Spring that caused a sensation and a riot on its debut in 1913. Another French modernist, Ravel, orchestrated Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, which originally existed only in a piano version. The "mighty handful" became a movement, stretching across two generations, with a self-conscious program to create a distinctive non-Western music-- initially Russian nationalist, but soon the leading edge of modernist music.

Against all this, Tchaikovsky was a hold-out. In the network, we see the heavy two-headed arrow between him and Mussorgsky: they criticized and insulted each other's music. Tchaikovsky continued to hold to the European path, lush romantic music with full touches of Russian orchestration, but still in the melody-and-chord tradition; he also creates the modern ballet repertoire, which had been stifled in old forms. Tchaikovsky was the one important Russian composer who had good contacts to the West during his career; he travelled widely in Europe in the 1880s, conducting his own works, meeting von Bulow in the Wagner network, and bringing back the latest European techniques to Russia. He and Mussorgsky had opposing niches. Here we see that niches in the music world are not merely vertical, not just the old generation against the new, but opposing ways to innovate. Tchaikovsky's niche is continued by his protégé Rachmaninoff (who also has network links to Rimsky-Korsakov and to the virtuoso pianist Liszt); the resulting combination in Rachmaninoff brings together spectacular piano technique, beautiful romantic melodies, and lush orchestration with overtones of Russian church bells.

To summarize: the networks contain more musicians than innovators. Many of them imitate their masters; Beethoven had many pupils, but chiefly they were flashy piano players rather than innovators. I have argued that creativity begins by internalizing a sense of the field, of what has already been done and who are the rival positions. Mozart had a tremendous memory for music that he had heard; he got this from so many different sources, as his father paraded the child around Europe, that he was able to blend many elements into his distinctly fluid style. And persons who internalize the field and sense the combinations can compose swiftly; they develop huge emotional energy, the sense of initiative and trajectory that enables them to produce large amounts of new work. Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven are all energy demons, workaholics, one might say, except that the modern cliché does not capture the delight they feel in their work.

And innovators tend to be closely tied to innovations in instruments: Bach began his career as a teenager repairing and building organs, becoming a virtuoso of what could be played on the big new instrument with both hands and feet. He grew up at the time when the grand organ was perfected, and this grandeur pervades his work. Beethoven from an early age spent much time with piano-makers, pushing the field of what can be done as pianos became stronger, louder and more resonant—creating his distinctive brand of dramatic music which he later transferred to the symphony. Musicians, like laboratory scientists, develop in a hybrid network of humans and their instruments, experimenting with the technical possibilities to find what can be discovered—in this case in the realm of sound.

Let me close with an example of innovative technique in the career of Descartes. Medieval mathematicians understood many of the concepts and operations of algebra, but they had to work them out verbally. Some abbreviations were developed, but solving a problem was still mind-fatiguing, until Descartes mechanized the process. He set up basic procedures: Organize every mathematical statement of knowns and unknowns by lining them up to the left and right of an equals sign. If more than one equation applies, line them up one above the other. Rearrange the terms by performing the same operations, such as adding or multiplying, to both sides of the equation. Substitute terms from one equation into another, until we get an equation for the term we are looking for. Rearranging the equations on paper becomes a mechanical process.

Today any school-child can do what the greatest minds before Descartes found difficult. And it opened up the path to seeking new techniques in mathematics: Descartes himself did it again with analytical geometry, and in applying the axiomatic method to philosophy.

Sophistication in math and philosophy came with the recognition that innovations in technique are the path to further discoveries. This also happened in music. Unlike amateurs who merely enjoy the music, creative composers look for the techniques previously used in their network, and construct new music by innovating in technique. Similarly, creativity in philosophy comes from acquiring the techniques—or should we say meta-techniques—of constructing new philosophies.