We have a truncated view of what William James is about. Bits and pieces are famous: The James-Lange theory that you feel afraid because you run away, not vice versa. A few famous lines: “the saddle-back of the present”; the world is “a blooming, buzzing confusion” (he meant, for an infant). Witty things he and Gertrude Stein said to each other when she was his student.

Pragmatist philosophy, of course: what is true is what works. This connects with his open-minded interest in religious experiences, including mysticism, even including drugs. James is no religious conservative, defending tradition and dogma. He investigates without prejudgements what religion is like in all its varieties, and what you get out of it-- his pragmatism again.

All this obscures the fact that James was a psychologist, and he became famous for his comprehensive text-book of psychology in the 1890s, before his late-life switch to philosophy and pragmatism. And he was not just a psychologist, but a medical psychologist, grounding psychology in the physiology of the body. When James entered adulthood in the 1860s, psychology as a research field did not yet exist, and his degree was in medicine. Thus his psychology is not just of the mind or the brain, but of the entire body.

James combined existing medical research with the experimental psychology then being developed in German laboratories, and to an extent in England. These 19th century experiments are now largely forgotten. They were launching an empirical study of the human mind, focusing on the senses by which persons experience the world, and on subjective processes such as time, idea-associations, and memory. In short, they were measuring the contents of human consciousness. But this “introspectionist” psychology was what behaviorist psychology, taking off in America around 1915, would reject for the next 60 years. The behaviorists declared the mind was a “black box” that could not be opened scientifically; instead they devised experiments to study overt behavior, for convenience using rats, and to some extent dogs and pigeons. Only when cognitive psychology started making a come-back in the 1970s did James’ topics again become a central focus for research.

What do we get out of James’ psychology of the 1890s? A surprisingly modern view, and on the whole better expressed and more usefully packaged than much of the neurophysiological psychology of today. There is no big break in the kinds of things we know. Contemporary cognitive psychology follows in the wake of the 19th-century work James was drawing upon; sometimes rediscovering what his era already saw but in lesser detail without today’s laboratory instrumentation.

Overview:

a. Three-part model: sensory input -- central channeling -- action output

b. All sensory experience is previously channeled

c. Experience speeds both recognition and misrecognition

d. All mental schemas are fuzzy

e. Conscious / unconscious is a continuum

f. Emotions are simultaneous with action, not prior

g. Habits facilitate action and free up conscious attention

h. To break a habit, put a different habit in its starting place

i. Will power is focusing attention at the beginning of a chain

j. A theory of Alzheimer’s

Three-part model: sensory input -- central channeling -- action output

From a physiological perspective, everything that we call psychological involves a 3-part sequence. It starts with sensory input of some kind: sight, sound, senses in the body or on its surface. Input flows into central process; what we usually call the brain, except this should not be confined within narrow borders, since the central processing involves connections not just among neurons inside the skull but all the other connections throughout the body. I suggest calling it central channeling, on the metaphor of channels becoming deeper and more strongly marked the more times an impulse has flowed through them.

Finally there is output in the form of action. As James views it, every impulse coming in from the senses and through the central channels flows out again, in the action part of the organism. At first glance, this sounds overly behaviorist, as if the organism is inert until something sensory comes in, wakes up the brain, and then the body moves its muscles and does something. But James sees the output action much more broadly: “from a physiological point of view, a gesture, an expression of the brow, or an expulsion of breath are as much movements as an act of locomotion.” [426] It would also include sweating, blushing, eye movements, changes in body temperature and blood flow to different parts of the body, stomach acid, speeding heart rate, saying something to oneself under one’s breath-- a range of things that includes what we would call emotion signs and thinking. For James, an emotion is a form of physical behavior, and so is cognition.

At this point, we don’t have to believe it. Take it as a theoretical generalization, which we can test in every single case of experience. Among other things, James is implying that thinking to oneself always has effects somewhere in the body besides in the brain itself; and also that any sensation that comes in not only goes into the brain system, but comes out somewhere is the body. As we shall see, much of this is in the realm of habitual channels and on the unconscious part of the continuum. The work of the psychologist is to trace it through the body. *

* James was about 20 years older than Sigmund Freud, and his work was earlier. Leaving aside Freud’s famous theories about sexual and aggressive impulses from early childhood onwards, we can say that both of these medical-doctors-turned-psychologist hit on a similar formulation: what is psychological in the narrower sense is also operative throughout the body. Their theories are psycho-somatic.

All experience is previously channeled

There is no such thing as pure experience, independent of filters or preconceptions. That is to say, the brain/processor is wired to see, hear, feel (etc.) certain kinds of things; and those wirings or channels change every time you perceive something. Learning a foreign language, it takes a while to recognize what those sounds are and how to parse them into syllables, words, and meanings. An English-speaker has to learn to hear the difference between vowel-sounds in French that are not significant in English. Someone with a slight knowledge of a language is prone to make what turn out to ridiculous misinterpretations. Successfully learning a language is a gestalt-switich; what was previously quite literally a buzzing confusion resolves itself into comprehensible utterances. An infant is in the same position, since their “native” language is foreign at first until it becomes grooved into the brain/ear/voice pathways of brain and muscle. The same thing happens later on if one learns to recognize tunes and harmonies in particular kinds of music; the first time you hear Stravinsky is a much different listening experience than when you become familiar with it; and the same was true historically when audiences had to learn to hear the sounds of Wagner, or for that matter Beethoven, Bach, or early polyphonic music.

Similarly with sight. Learning to read begins with coming to see certain shapes as letters distinctive from each other. Learning to read a foreign language is another gestalt-switch, as when a Westerner first starts to recognize particular Chinese characters. Sight pervasively structures our experience-- what we think of as “the world” around us is mainly what we looks like to us-- and this too had to be built up in early childhood. And throughout one’s life, as well: houses look different when you are thinking about buying one of them, or if you become interested in architecture. You see a different world each time you pay attention to it, although on autopilot it is only a familiar blur.

The same again with the physical, palpable world. The gestalt-switch is most apparent in learning to ride a bicycle rather than falling over or to swim rather than sinking in the water; these are a matter of attending to certain sensations in your muscles, your sense of balance, and where you put your attention (you become a skier when you stop focusing on your legs and focus on the spot where you are going). These actions, which are initially tricky and call for re-wiring the central channels from what they did before, show most dramatically that one’s physical sense of the world is a bundle of sensations in your body, the sensations of moving your muscles in a particular way, and its coordination with other senses like vision. A child learning to walk is also constructing a brain-channeled world that is walkable, and a body that fits in that world.

The point is not just of philosophical or theoretical interest. All practical skills are of this sort; the difference between being good at something, passable, or inept are in the packaging of these bundles of experience. Social skills (not much of a concern in James’ psychology, but central for a micro-sociologist) are ways of shaping one’s sensation/central-channel/action pathways. These experiences account for how some persons are talkative or shy; aggressive and violent or victimized; socially connected or alienated (and in what kinds of situations).

Experience speeds both recognition and misrecognition

With greater experience, certain kinds of perceptions are easier and quicker. You see more at a quick glance; you can construct the unseen or blurred part from the part that your brain recognizes. My wife does not have very good eyesight, but she is an excellent driver, including at rather high speeds; she says that she recognizes what other drivers are going to do and steers accordingly. Many successful college quarterbacks fail when they reach the professional league; it can take several years training to “see the field” in fractions of a second; and quarterbacks who manage to do this generally have much longer careers than other players who rely on muscle and quickness. It is a whole-body skill, not just in the vision and hand-eye-(legs) coordination, but in a perceptual gestalt that slows down time where other players see a blur.

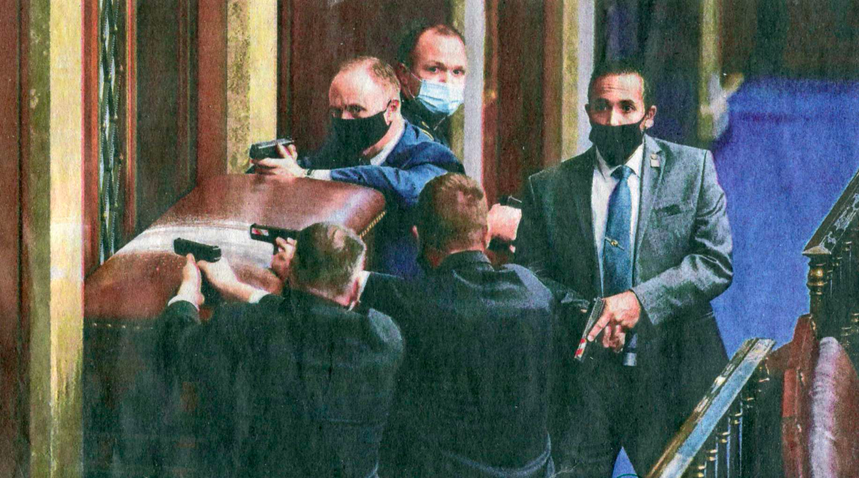

James comments that the same sensory/ channeling process that makes for experienced recognition also is responsible for illusions. At a distance, an erect figure at the side of the road may look like a person but up close turns out to be a road sign. This is the brain filling out a sight on the basis of partial information. If you do speed-reading or glancing through messages, it is easy to mistake what is actually said (expecting bad news, it looks worse than it really is). Eye-witness testimony in crimes is often unreliable; usually the event is blurred because sudden, unexpected, or highly emotional; the victim can pick the wrong person out of a line-up while feeling convinced it was the perpetrator s/he faced. The feeling of certitude comes from forming a gestalt-- not at the time of the crime, but later when you fit one of the faces into your blurred memories.

This does not mean that eye-witness knowledge is always unreliable; if that were the case, no observer would ever learn anything accurately. The difference is in the total eye-brain-body configuration of whoever is doing the observation. Ethnographers train themselves to observe the details-- they are not merely caught up in the action, but focusing on their professional task of observing, commiting key details to memory, and recording them in field notes. A blanket statement-- all personal observation is fallacious-- is inaccurate; we can specify what makes some observers more accurate than others. It is the difference between plunging a non-athlete into a pro football game, and the way the star quarterback sees the field.

James summarizes laboratory research on the question: how long is the present, the “now” as a moment in time? Philosophers are prone to argue that the present moment is so elusive that it is virtually non-existent, if not at actual illusion. Since Xeno, the argument has been made that each little bit of time can be subdivided, and so on to infinitesimal regression. Buddhist philosophers in India argued thus as a proof for the non-existence of the world as it is humanly perceived. James, however, regards these are merely intellectual arguments; instead, look at experience when subjects are asked to compare visual images flashed at different speeds. A useful experiment is to look at something, then close your eyes, and count how long the image remains visible inside your eyelids. Especially when looking at objects which have bright and contrasting colors or light and shade, you see that the image slowly fades and become more blurred. From similar experiments, James estimates that the present moment lasts between 7 and 12 seconds. --Perception is not of an instant in time; it is perception of things that have a deep enough channel in your brain so that you can see them. There is no knife-blade of the present; better put, it is a “saddle-back of the present” as you ride the horse of your senses/brain/body along a course of experience.

This has an important relevance for social interaction. Garfinkel’s ethnomethodology of what he calls the practices of everyday reasoning includes the principle: what is communicated by other people is often ambiguous or meaningless; but we adopt an attitude of wait-and-see, expecting the meaning to emerge. Garfinkel’s famous breaching experiments were designed to show that even in situations deliberately contrived to be meaningless, subjects assumed there was a hidden meaning that would eventually emerge. A more mundane example is the experience of hearing someone say something, which at first you misrecognize-- until a few seconds later the utterance sounds meaningful in retrospect..

The reason you can reinterpret what you heard, eventually getting the words connected with the right set of syllables, is because auditory memory has about the same time-present as visual memory; the words are reverberating in your brain-memory for up to around 7 seconds, and this makes it possible to re-hear their meaning. It is this saddle-back of present hearing that makes it possible for simultaneous translators at international conferences to translate what the speaker has just said a few seconds back, while also listening to what s/he is saying that will have to be translated next. And it is how all of us make our way through a perceptual world that is deeply ambiguous, at least in detail, all the way through. And that is because:

All mental schemas are fuzzy

We think of the world around us as full of physical objects, which mostly remain stable across the hours and days of everyday life. But is this really so? Moving around, we view things from many different angles and distances. Tables, chairs, trees, houses, faces and bodies-- the objects may be the same but we see them from thousands of different angles, in different lights and colorings. Out of all these different mental snapshots, which one is your image of how things look? In the channeling of neural circuits, a table is not just one ideal picture of a rectangle with legs at the corners; it is all the neural circuits that have been grooved by perceiving it in different perspectives.

All of them together is the mental object; it is a fuzzy composite, not a single clear image. They hang together because parts of them overlap. They have a central core, but also a lot of non-overlap. Your mental images have fuzzy edges-- but this is a figure of speech, because images are fuzzy all the way through.

As a practical matter, this causes no problem in navigating our familiar surroundings; especially since deeply grooved circuits tend to complete the gestalt with only partial information. For this reason, James comments, artists have to unlearn their normal, neurally lazy way of perceiving the world, and to train oneself to look at how things actually appear in particular perspectives and lights.

Philosophers in the Platonic tradition have taken such multiplicity of experience as a reason to reject the senses and rely on pure, abstract images in the mind as the source of truth. But James points out there is no reason to believe such images exist in the brain. Experience of objects is stored in fuzzy composites. When you attempt to call to mind a particular image, it is generally fuzzy; if you close your eyes, the hynogogic images that appear to be inside your eyelids are vague and flickering, prone to quickly shift into related shapes. In dreams, images are rarely sharp and clear, and dreamers do not stare fixedly at a sight but move through the dream-- which is why dreams morph into strange visual associations, as one would expect from attention flowing rather randomly among the channels of complicated neural circuits. To the extent that there are mental schemas, they are fuzzy complexes.

Philosophical Platonists argue that their Ideal types are the only way to account for truth and reason. James offers an alternative: there is no sharp divide between a correct image and incorrect ones. They are all approximations, all partial and incomplete. Relying on a small slice of experience and letting neural grooves complete the rest of the gestalt is nevertheless a practical way of getting around in the world; if it turns out to be hasty misrecognition and results in a bad mistake, the gestalt is usually reset by the shock. James’ emphasis on the fuzziness of concepts goes along with his pragmatism: truth is what you call it when the outcomes are the ones that you are aiming at.

This is also the way it works when we engage in reasoning. All of our calculating and decision-making takes place in some period of time, not in abstraction from time and place. Whether a decision turns out to be right or wrong is decided by how it turns out. John Dewey, James’ pragmatist follower, emphasized that we are always moving along trajectories of action; at any particular moment, we aim at some end, and choose means to get there. But as your chain of actions goes along, typically the end-target gets adjusted; means become ends and vice versa. This is true of scientific research as well as business, politics, and everyday life. In science, the initial research question often morphs into something else; if solving it is difficult, it becomes perceived as an ill-posed question. Most breakthroughs are shifts to new ways of conceptualizing what we are concerned with.

It is a philosophical and intellectual prejudice that the world should be clear and exact. To assume that every assertion is either right or wrong, true or false, with no area of overlap, is unrealistic, and an impractical way to proceed. In actual experience, most problems we can pose ourselves fork three ways: probably yes, probably no, and undecidable. None of this is permanent; time and human projects move along; what is undecidable at one time may move into a clearer probability zone later. Being realistic implies we should expect new areas of undecidability will emerge as we go along.

Conscious/unconscious is a continuum

There is no sharp dividing line between conscious and unconscious. What we ordinarily regard as consciousness is concentrating our attention and looking for particular kinds of things that feel significant at that moment. (Such focus is also intensified activity in particular neural circuits in the brain.) At the same time, a strong focus of attention also de-focuses other things. When we are not particularly focusing attention, things run off more or less automatically-- this is true of ordinary habitual actions like walking, or moving your fingers if you know how to type on a keyboard. There are also states of experience when one is not concerned to be attentive to anything, when you are feeling lazy, drowsy, relaxed; and this has a borderline area in which you fall asleep. As usual in James’ worldview, gradations of consciousness exist but they range along a fuzzy continuum, indeed along a fuzzy number of continuums (continua).

This has implications for his theory of emotions, as well as his theory of habits.

Emotions are simultaneous with action, not prior

“All consciousness is motor... Every impression which impinges on the incoming nerves produces some discharge down the outgoing ones, whether we be aware of it or not... We might say that every possible feeling produces a movement, and that the movement is a movement of the entire organism and of each and all its parts.” [372]

James goes on to examine the most characteristic of these bodily movements, i.e. emotions. Here he expounds what is called the James-Lange theory. “My theory... is that the bodily changes follow directly the perception of the exciting fact, and our feeling of the same changes is the emotions.... Common sense says... we meet a bear, we are frightened and run... [But] this order of sequence is incorrect; the one mental state is not immediately induced by the other; bodily manifestations must be interposed between... We feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble.” [377]

James goes on to apply this model to milder emotions, and urges the reader to observe oneself. “When worried by a slight trouble, one may find that the focus of one’s bodily consciousness is the contraction, often quite inconsiderable, of the eyes and brows. When momentarily embarrassed, it is something in the pharynx that compels either a swallow, a clearing of the throat, or a slight cough...” [380] Observing closely the sequence in time, we find “every one of the bodily changes, whatever it be, is FELT, acutely or obscurely, the moment it occurs.” [379]

The thought-content of the emotion comes after the bodily changes, not before. Genuine emotions overtake us via the body. A faked emotion usually does not come across as genuine, although we may mimic the more easily controlled voluntary muscles of face or posture, because it lacks the power of the involuntary changes--- like trying to imitate a sneeze, James comments.

Next comes: “... the vital point of my whole theory: If we fancy some strong emotion, and then try to abstract from our consciousness of it all the feelings of its bodily symptoms, we find we have nothing left behind, no ‘mind-stuff’ out of which the emotion can be constituted.” [380]

James is not arguing against the existence of the mind or of consciousness. He is observing in detail the full-body process within which “mind” exists, and the up-and-down slopes of feeling and attention that constitute our consciousness.

Habits facilitate action and free up conscious attention

A habit is a deeply grooved chain: an initial perception to set it off; the brain circuits; the physical action. These are chained together in a repeated circuit: in the habit of walking or running, tipping your bodily balance forward and moving your legs so that the other leg catches you before you fall; the sensation of the foot hitting the ground, the sense of where your balance point is, are the perceptual inputs, moving the chain along to another input point, and so on. Once you learn how to walk, this becomes unconscious; no attention has to be directed to these repeated connections, and this leaves you free to attend to other matters, such as changing direction, noticing other people, or looking around. Thus habitual actions at a more basic (and earlier-learned) level are the key to more complex and mindful actions. It is James’ continuum of unconscious/conscious again. As noted, here James converges with Freud; the chief difference being that Freud is concerned with dramatic unconscious action-impulses and their physiology (sex and aggression, along with various strong emotions); James portrays unconscious perception/brain-channel/body-action as constitutive of everything that humans do (and probably other animals as well).

Habits enable you to get yourself going when you don’t feel like it. Putting off writing for one reason or another; putting off exercizing when you don’t have the energy; procrastinating... The tactic is to start the first part of a routine and let the sequence pull you into its rhythm. Don’t start with the hardest; start with something easy or something you like -- your favorite stretch, leave the crunches for later, when they will click in on their own. Overcome writer’s block by correcting your latest text; if you don’t know what comes next, recopy your notes or outline-- this gets you focusing on the sequence of topics (what point to make before what) as well as getting you started writing. Making small changes makes it easier to make bigger changes: a new idea, some wording you can use; soon you are drawn to keyboard and finding one line leads to another.

When you really feel lethargic, get up and do something easy and automatic. I find that walking around the garden with clipping shears in hand, or just picking off dead leaves, becomes pleasantly addictive; the more you do it, the more things you see to do. James’ sequence is set off: perceptual starting points, familiar channels, bodily actions, leaving you cued in to more starting points. Today the terminology would refer to them as “affordances,” the appeal that objects in your environment make for you to do something with them. Except that they are not affordances for everybody; it is your own distinctive habit sequences that give them their action-triggering qualities.

Professional techniques are habits at a higher skill level. What makes an artist or a musician successful are the techniques they have acquired: how to sketch the first lines that set the focus of what you are painting; how to expand a rhythmic motif and put forward-leaning tension into a chord sequence. They find their style when they acquire a fertile combination of techniques, which become engrained to run off automatically. Mozart, who started acquiring such techniques when he was three years old, eventually reached the point where starting with any little bit of tune would set him off creating something new. Because techniques have trajectories, once you launch in, it carries you with it. This is the difference between a banal routine and a habit which is enjoyable, even fun: it has a direction, so that the little details it encompasses are meaningful, part of project’s gestalt. High-level habits of this sort contain their own built-in motivation. Habits of this sort are the opposite of boredom.

To break a habit, put a different habit in its starting place

James discusses “bad habits” as any kind of cue-channel-action sequence that you end up wishing you wouldn’t do. But since habits are so deeply grooved in the nervous system, how can you overcome them? They jump in automatically from the starting point. At the end you may add -- I wish I didn’t do that-- but that only adds something further to the end of the sequence. James’ solution is to break a habit by having some other habit interfere with it. *

* James also discusses instincts-- habitual sequences that are hard-wired into the nervous system. If these could never be overcome, James points out, humans could never have evolved to doing anything new, and history would not exist. The hard-wiring does not disappear; humans have a flight-or-fight arousal in the hypothalamus, but persons can add other channels that shape when and how the physiological response is tripped off. [388]

The substituting habit must start from the same cue, the perception that triggers the undesired habit. If over-eating starts with opening the refrigerator every time you walk past it, the solution is to chain something else to seeing the refrigerator, or the food inside it. One way to do this is to create a habit of focusing attention on the feeling in your stomach: do I feel hungry, or satiated? If the latter, let the chain of thought follow-- I don’t really feel like eating, the desire is just in my head-- and the action of not looking for food. Psychological experiments show that persons who eat too much do not feel hungry all the time, but instead react very impulsively to the sight of food. *

* Anthropologists have pointed out that in some Polynesian cultures, an insult or a mishap that would otherwise make persons angry, is headed off. Instead of expressing anger or taking action, the cultural response is immediately to think, has someone violated a taboo or brought evil mana here? While thinking about this (an anthropologist told me such persons would get a perplexed look on their face), the anger response calms down. They have inserted a cue immediately after the first anger arousal, that leads in a different direction.

Will power is focusing attention at the beginning of a chain

At this point, James raises the question of the existence of will. But his discussion is not about free will as a metaphysical issue; it is a matter of seeing what we are referring to in practice. If there are acts of free will, we must be able to observe what they look like; where they are located in the flow of time and action. Where they are not located is after a habit has run itself off; repenting at the end, telling yourself not to do it again, are failures of will.

An act of will must come at the opening cue, acting quickly to re-route the following habit sequence. Here the saddle-back of the present helps out. Nothing is instantaneous; every psychological process takes some time, even if a short one. James estimates the opening is about a half-second:

“Mental spontaneity... is limited to selecting amongst those [ideas] which the associative machinery introduces. If it can emphasize, reinforce, or protract for half a second either one of these, it can do all that the most eager advocate of free will need demand.” [286]

Modern research on tape-recorded conversation finds that humans can be distinctly aware of periods of 0.2 seconds-- 5 beats per second, like counting one-al-li-ga-tor, two-al-li-ga-tor, three-al-li-ga-tor. We can hear pauses as short as 0.1 second. Thus a half-second is ample time to reverse a course of action, even if it is a deeply channeled habit. The key is to focus one’s attention on that cue, instead of letting it slide by on a low level of the unconscious/conscious continuum. James refers to this as “the effects of interested attention and volition”. Your attention must be interested in what you are focusing on, if it is to turn the sequence into a volition. Will power is a high degree of conscious attention, exercized at moments where you have pre-prepared habit sequences among which you can switch.

Thus putting a new habit in place of a bad habit involves a series of moves, some of them far back in time. Deciding something is a bad habit-- that is usually easy. Figuring out and carefully observing what is the cue that sets it off. Formulating a new habit sequence that can be inserted. And finally, making the substitution in real time.

James is not only a pragmatist. He is the most practical of psychologists.

A theory of Alzheimer’s

James did not discuss Alzheimer’s disease or adult dementia, but his psychology at many points is directly relevant. Alzheimer’s is above all a breakdown of memory, starting with short-term memory; eventually it can proceed to full-scale failure of the nervous system. Thus a William James theory of Alzheimer’s can be constructed from his analysis of memory, habit, and the sensation/channel/action sequence. And being a pragmatist, his theory tells a person what to do about it-- above all the person whose own memory is failing. It is a theory that enables rather than restrains people.

This is what James has to say:

Aging and the speed of time

“... a time filled with varied and interesting experiences seems short in passing, but long as we look back. On the other hand, a tract of time empty of experiences seems long in passing, in retrospect short... Many objects, events, changes, many subdivisions, immediately widen the view as we look back. Emptiness, monotony familiarity, make it shrivel up.

“The same space of time seems shorter as we grow older-- that is, the days, the months, and the years do so; whether the hours do so is doubtful, and the minutes and seconds to all appearances appear about the same... In most men all the events of manhood’s years are of such familiar sorts that the individual impressions do not last. At the same time, more and more of the earlier events get forgotten, the result being that no greater multitude of distinct objects remain in the memory...

“So much for the apparent shortening of tracts of time in retrospect. They shorten in passing whenever we are so fully occupied with their content as not to note the actual time itself. A day full of excitement, with no pause, is said to pass ‘ere we know it.’ On the contrary, a day full of waiting, of unsatisfied desire for change, will seem a small eternity... [Boredom] comes about whenever, from the relative emptiness of content of a tract of time, we grow attentive to the passage of time itself... The odiousness of the whole experience comes from its insipidity; for stimulation is the indispensable requisite for pleasure in an experience.” [290-91]

Active memory circuits and dated memories

James goes on to make a distinction between our feeling of past time as a present feeling, and our reproductive memory, the recall of dated things: “Since we saw a while ago that our maximum distinct perception of duration hardly covers more than a dozen seconds (while our maximum vague perception is probably not more than a minute or so), we must suppose that this amount of duration is pictured fairly steadily in each passing instant of consciousness by virtue of some fairly constant feature in the brain-process to which the consciousness is tied. This feature of the brain-process, whatever it may be, must be the cause of our perceiving the fact of time at all.

“The duration thus steadily perceived is hardly more than the ‘specious present’... Its content is in a constant flux, events dawning into its forward end as fast as they fade out of its rearward one, and each of them changing its time-coefficient from ‘not yet,’ or ‘not quite yet,’ to ‘just gone,’ or ‘gone,’ as it passes by. Meanwhile the specious present, the intuited duration, stands permanent, like the rainbow on the waterfall, with its own quality unchanged by the events that stream through it...”

“Please observe, however, that the reproduction of an event, after it has once completely dropped out of the rearward end of the specious present, is an entirely different psychic fact from its direct perception in the specious present as a thing immediately past... In the next chapter, we will turn to the analysis of what happens to reproductive memory, the recall of dated things.” [292-93]

Ingredients for good memory

“Memory thus being altogether conditioned on brain-paths, its excellence in a given individual will depend partly on the NUMBER and partly on the PERSISTENCE of these paths.” [299]

Innate retentiveness of neural connections

James recognizes individual differences in memory that are physiologically based: “The persistence or permanence of the paths is a physiological property of the brain-tissue of the individual, whilst their number is altogether due to the facts of his mental experience. Let the quality of permanence in the paths be called their native tenacity, or physiological retentiveness. This tenacity differs enormously from infancy to old age, and from one person to another. Some minds are like wax under a seal-- no impression, however disconnected from others, is wiped out. Others, like a jelly, vibrate to every touch, but under usual conditions retain no permanent mark. The latter minds, before they can recollect a fact, must weave it into their permanent stores of knowledge. They have no desultory memory.

“Those persons, on the contrary, who retain names, dates and addresses, anecdotes, gossip, poetry, quotations, and all sorts of miscellaneous facts, without an effort, have desultory memory in a high degree, and certainly owe it to the unusual tenacity of their brain-substance for any path formed therein. No one probably was ever effective on a voluminous scale without a high degree of this physiological retentiveness. In the practical as in the theoretic life, the man whose acquisitions stick is the man who is always achieving and advancing, while his neighbors, spending most of their time in relearning what they once knew but have forgotten, simply hold their own.” [299-300]

Adding and losing connections; aging

Even so, everyone ages: “But there comes a time of life for all of us when we can do no more than hold our own in the way of acquisitions, when the old paths fade as fast as the new ones form in our brain, and when we forget in a week quite as much as we can learn in the same space of time. This equilibrium may last many, many years. In extreme old age it is upset in the reverse direction, and forgetting prevails over acquisition, or rather there is no acquisition. Brain-paths are [now] so transient that in the course of a few minutes of conversation the same question is asked and its answer forgotten half a dozen times. Then the superior tenacity of the paths formed in childhood becomes manifest: the dotard will retrace the facts of his earlier years after he has lost all of those of later date.” --Without using the term “Alzheimer’s”, James describes some of its symptoms.

More paths, more memory

“So much for the permanence of the paths. Now for their number. It is obvious that the more there are of such [neural paths in the brain, associated with a particular event], and the more such possible cues or occasions for the recall of [that event] to the mind, the more frequently one will be reminded of it, the more avenues of approach to it one will possess. In mental terms, the more other facts a fact is associated with in the mind, the better possession of it our memory retains. Each of its associates becomes a hook to which it hangs, a means to fish it up by when sunk beneath the surface.”

Thinking keeps the circuits flowing

“The ‘secret of a good memory’ is the secret of forming diverse and multiple associations with every fact we care to retain. But this forming of associations with a fact, what is it but thinking about the fact as much as possible? Briefly, then, of two men with the same outward experiences and the same amount of mere native tenacity, the one who THINKS over his experiences most, and weaves them into systematic relations with each other, will be the one with the best memory.

“Most men have a good memory for facts connected with their own pursuits. The college athlete who remains a dunce at his books will astonish you with his knowledge of men’s records in various feats and games, and will be a walking dictionary of sporting statistics. The reason is that he is constantly going over these things in his mind, and comparing and making series of them. They form for him not so many odd facts, but a concept system-- so they stick. So the merchant remembers prices, the politician other politicians’ speeches and votes, with a copiousness that amazes outsiders, but which the amount of thinking they bestow on these subjects easily explains.

Intellectual projects bond numerous fact-memories

“The great memory for facts which a Darwin and a Spencer reveal in their books is not incompatible with the possession on their part of a brain with only a middling degree of physiological retentiveness. Let a man early in his life set himself the task of verifying such a theory as that of evolution, and the facts will soon cluster and cling to him like grapes to their stem. Their relations to the theory will hold them fast; and the more of these the mind is able to discern, the greater the erudition will be.” On the other hand: “Unutilizable facts may be unnoticed by him and forgotten as soon as heard. An ignorance almost as encyclopaedic as his erudition may co-exist... Those who have much to do with scholars will readily think of examples.” [301-302] -- James comes down after all on mental habits more than the genetics of brain capacity.

Rote learning is onerous and ephemeral

“The reason why cramming is such a bad mode of study is now made clear. I mean by cramming that way of preparing for examinations by committing points to memory during a few hours or days of intense application immediately preceding the final ordeal, little or no work having been performed during the previous course of the term. Things learned thus in a few hours, on one occasion, for one purpose, cannot possibly have formed many associations with other things in the mind. Their brain-processes are led into by few paths, and are relatively little liable to be awakened again. Speedy oblivion is the almost inevitable fate of all that is committed to memory in this simple way. ... On the contrary, the same materials taken in gradually, day after day, recurring in different contexts... and repeatedly reflected upon, lie open to so many paths of approach, that they remain permanent possessions.

“One’s native retentativeness is unchangeable. It will now appear clear that all improvement of the memory lies in the line of ELABORATING THE ASSOCIATES of each of the several things to be remembered.” [302]

In other words, connecting facts with a theory, or with some larger purpose, is the best way to remember them, and that means understanding how they are used. It is the difference between trying to learn a foreign language by memorizing tables of verb forms, and hearing them in all sorts of real-life contexts.

Now to put James to work on the problem of Alzheimer’s. It affects both short-term memory and long-term memory (what James refers to as reproductive memory). Both deteriorate over time, while short-term memory appears to deteriorate first, or at least it becomes seen as a problem earlier.

Typical short-term memory problems include: losing track of practical things you are trying to do; repeating yourself in conversation without being aware of it; losing things by being unable to remember where they are. Long-term memory problems range from forgetting names of acquaintances; not recognizing familiar people; losing memory of personal experiences; losing general knowledge you once had; losing the ability to understand or speak a language; at the extreme, neural degeneration destroys motor skills and bodily functions and can be a cause of death. What does James offer by way of explanation of these phenomena? Where does his analysis suggest amelioration, and for what ranges of severity?

Forgetting particular names

Short-term memory has fewer neural connections than long-term memory, so we would expect it to deteriorate first. I will discuss the various kinds of memory failure starting with those that set in earliest, and these are mostly short-term memory. But one kind of long-term memory-forgetting affects people even in their 50s or earlier, forgetting particular names.

James says: “We recognize but do not remember it-- its associates form too confused a cloud... We then feel we have seen the object already, but when and where we cannot say, though we may seem to be on the brink of saying it... what happens when we seek to remember a name. It tingles, it trembles on the verge, but it does not come. Just such a tingling and trembling of unrecovered associates is the penumbra of recognition that may surround any experience and make it seem familiar, though we know not why.” [305-06]

Because they are particular, names of people or places have fewer occasions for use than more generic words-- unless it is a place-name you are constantly writing or referring to (like your address), or a name of someone you constantly invoke. But if you have had hundreds or thousands of professional or social acquaintances in your life, it is not surprising that you should forget most of them after a while-- even though it is embarrassing to meet someone suddenly and be unable to connect a name to the face. It should be considered bad manners to accost an old acquaintance with a question like “You remember me, don’t you?” Today’s informal manners, which includes introducing yourself by your first name only, doesn’t help much. On the whole, forgetting particular names is trivial and ought to be recognized as such. If you feel insulted because your name isn’t on the tip of someone’s tongue, it is probably because you aren’t as important as you think you are.

Having trouble bringing to mind the names of persons who are professionally important when you talk about topics in your field-- like a sociologist unable to recall the name of Weber or Bourdieu-- is a more significant sign of loss of neural connections. But the fact that one can usually ferret out the desired name by thinking of their books or controversies indicates most of the important connections are still in working order. This is a better search method than trying to remember what letters of the alphabet are in the missing name, since letter combinations are more arbitrary, and the search field is hard to narrow down by that route.

Forgetting your intention

In the realm of short-term memory, among the earliest failures are forgetting what you set out to do. These are typically minor practical tasks: going downstairs to the kitchen to get a glass of water, but getting side-tracked along the way (picking up the newspaper and reading it; putting away dishes from the drain; etc). The original intention gets lost. This is called being absent-minded or scattered, but can also be a sign of memory loss. The explanation is in James’ model: habits are set off by initial cues. If you are in the habit of keeping the kitchen cleared up, the sight of dishes now dried in the drain or the dishwasher invokes the habit of picking them up and putting them away. They are “affordances” -- objects are occasions for the actions you can do with them. But it is their link to habits that creates problems for short-term memory. James suggests putting a different habit in the place of an undesired habit. In this case, what is undesired is not the habit itself (putting away dishes), but letting it interfere with your intention (getting a glass of water). A solution would be to keep a cue with you of what you set out to do-- such as carrying an empty glass with you downstairs, and paying attention to it even as you walk past the habit-triggering dishes and other side-tracks.

Can’t remember whether you did something or not

Another type of short-term memory problem has less to do with remembering what you set out to do, than remembering whether you have already done it. (Do I need to brush my teeth now, or did I just do it?) The action is a familiar habit; you haven’t lost the neural-and-muscle memory of how to do it; and the sight of the toothbrush by the sink cues it off. The problem is the opposite of getting side-tracked. This is not exclusively a problem of aging. Many people go back to check whether they locked the door behind them as they leave the house; it is a form of Freudian anxiety more than memory loss per se (something similar could be said about certain kinds of name-forgetting, like names of people you have bad feelings about).

What is relevant here is the distinction between remembering what (some thing or action) and remembering when (you encountered the thing or did the action). Very familiar things/actions are towards the unconscious end of the continuum anyway; you have been through them so many times it is impossible to remember every time. James wrote: “If we remembered everything, we should on most occasions be as ill off as if we remembered nothing. It would take as long for us to recall a space of time as it took the original time to elapse, and we should never get ahead with our thinking.” [306] It is useful to forget most of the time-dating so you can get on with your life.

But in short-term memory, remembering-when is important since it keeps you from repeating the same thing over and over. This is an aspect of consciousness over and above the content of the short-term memory itself: not what it was, but also that it is marked in a span of time. Remembering-when, for banal everyday activities with no particular demand on attention and no emotional significance, is perhaps the least-connected in neural circuits of any experience. On the whole, it is destined to be left behind in the rear-view mirror of memory rather quickly. How quickly? James says the specious present is about 12 seconds and “our maximum vague perception is probably not more than a minute or so”. When you can’t remember whether you just brushed your teeth or not, how long does it take before that thought-process sets in? I don’t know if anyone has tried to measure this; a James-based conjecture would be-- certainly not within 12 seconds. Would it be in the “vague perception” range between 12 seconds and about 60 seconds? Beyond a minute, you have no sense of immediacy at all, and it is in the realm of past memories, which supposedly get drained out when you next sleep and dream.

I raise the point mainly as a practical suggestion for persons who have the problem of remembering whether or not you did something recently. The strength of short-term memory is affected by how much focused attention is placed on it: James argued that will-power consists in adding a half-second of sharply focused attention to any cue/action sequence. If you set off a stop-watch every time you finished brushing your teeth, this might furnish information about where your zone of remembering-when-failure is located in time. But aside from any contribution to psychology, it might add intensity to the remembering-when process-- it would be a practical antidote.

And as an antidote, it may well have a future history. Would the stop-watch routine start fading out as an antidote to the remembering-when failure? At some point, would you forget what the purpose of the stop-watch was? Would it extend the befuddlement-free zone for x minutes at first, then a shorter x-minus and so forth? This would be a measure of deterioration as well as a self-monitoring technique.

Repeating yourself in conversation

Similar analysis would apply to repeating yourself in conversation. Since this is a matter of degree, it is not clear whether forgetting whether you just brushed your teeth happens earlier than forgetting what you just said. But repeating in conversation is more socially disruptive and therefore more noticable; forgetting in little personal tasks is more private, and not on a whole a serious practical problem unless one spends all one’s time brushing one’s teeth.

Before setting it down to Alzheimer’s, we should note there are circumstances in which people of all ages repeat themselves. In arguments, especially as they grow heated, antagonists tend to interrupt each other, trying to talk each other down-- struggling over controlling the speaking turn as well as the content of what is said. Recorded conversational analysis shows that as opponents talk at same time, it becomes useless to make any connected argument, and the determined arguer repeats the words they most insist upon. Arguments that escalate to violence typically reach the phase of extended verbal repetition of insults. [data and references in Collins 2008] On a larger scale of contention, participants in protest demonstrations usually chant the same slogans over and over. Repetition here is a combination of emotional and strategic.

Drunks also tend to become very repetitive as they get more intoxicated (which is why being around drunks is boring if you are not drunk yourself). But in a bleary way drunks epitomize the central quality of sociable talk (phatic talk), where the main concern is just to keep the conversation going. Conviviality visibly fails when there is nothing to say, or just when there are embarrassing pauses; hence banal small talk about the weather. If it is a party or reception where many people are present, often the same things are said over and over in different conversations. Thus it is not just people with Alzheimer’s who repeat themselves.

What is distinctive must be the lack of conscious awareness that one is being repetitive; together with repetition in a short period of time. Couples or friends who have had many sociable conversations will often bring out the same reminiscences, stories and jokes; usually there is a sense that we have heard this before, but it is enjoyable to tell it again, like singing a song. This is phatic repetition. In leisure chatting, it is not unusual for the same topics, even the same phrases, to repeat. Such talk is deeply grooved verbal habits; it is a chatting routine. Lack of conscious awareness of repeating oneself is not necessarily a sign of neural deterioration. The best criterion, I suggest, is the length of time between one repetition and the next.

Here again there is a lack of data with the necessary detail. My impression is that very repetitive old people do not repeat themselves within 12 seconds-- the stretch of the Jamesian present. My guess it is more in the realm of 5 minutes or so. For people not yet at that advanced stage, it can be half an hour or more, even a day. Measuring the gap between repetitions would be an indicator of the extent of deterioration.

On the practical side, if a person repeats something once, there is no way of knowing when to start the stop-watch-- of knowing what phrase is going to be repeated. But if they typically repeat multiple times, one could note the second instance and measure subsequent repetition gaps. Doing this yourself may raise self-consciousness about repetitions, and thus improve neural connection. This is not the same as the other person saying, “You already said that,” -- which does not seem to have any effect. The heightened consciousness would have to be forward-looking: not so much looking out to avoid repetitions, but just to pay attention to the time-span itself.

Loss of long-term memory

There is a certain amount of long-term memory loss in the normal course of life. As James says, you need to forget a lot of detail, especially about memory sequences, if you are to have your brain free to do something else. Much of forgetting particular names falls into this category. Losing long-term memory includes the following, roughly in the order in which they happen: losing general knowledge; getting lost by not recognizing your familiar environment; not recognizing persons you know well or forgetting their names; losing language; losing muscle memory for motor skills.

On the whole, this is a process of losing neural connections; at first by lack of current activity and interest; further undermined by deterioration through aging. An example: My grandmother lived to be 103. Her husband for 53 years died when she was 75; a few years later her daughter (her only child) moved her out of the house she had lived in for 30 years, and near where her relatives were located, to a distant city. My mother insisted that her mother stay out of the kitchen and just sit down. Since in my memory (having lived with my grandparents for considerable periods growing up) Granny spent most of her life in the kitchen, this was tantamount to taking away most of her interests, her routines, and her neural circuits. A few years later, mother moved Granny into a nursing home. By the time she was in her late 80s, when I would visit Granny, she did not recognize me. At times, she would call me by the name of her nephew in Germany. She stopped being able to speak English (which she had spoken since age 22). When she did speak, she was still able to speak German; when her nephew did come for a visit, they were able to converse. In her nursing home years, she spent all her time in bed, barely able to move. This continued for about 20 years until she died. Apparently she could still recognize her daughter, who visited her from time to time. When mother died of cancer, no one told Granny, assuming she could not understand what was said. Granny died a few weeks after mother no longer came to see her.

These are typical patterns. Brain-circuits stay alive to the extent they are activated; if not, they fade out.

The main counteractive (if not cure) to long-term memory loss is to do things frequently that increase neural connections. As James emphasizes, this means paying attention with a sense of interest; and this happens when doing things not as a flat routine but with a trajectory. In his view, persons like Darwin were not unusually intelligent nor had especially retentive brains; it is having a project that connects things into a sought-for pattern that increases memory. His advice would be: if you have any intellectual interests, cultivate them even more as you get older. The same would be true for any interest that involves poring over a lot of information (sports statistics or stock market, whatever). If one is concerned about losing memory of life events, a counter would be to collect old photos and materials and compose your autobiography. If that is overly self-centered, you could make a project out of the biographies of other people.

In advanced stages of Alzheimer’s, people have difficulty following a conversation. Learning to focus on the non-verbal signs other speakers are giving off would be a project that provides interest and increases attention; probably it would reduce one’s sense of isolation and may add to a more comfortable feeling for the others. These are the self-reinforcing spirals. Isolation and passivity reduces neural connections and breeds more of the same. Active participation, on whatever level, has the opposite results.

Ending

It is conventional to regard Alzheimer’s as a disease, and therefore something for which there is a specific medical cure. But it may be that there is no such thing as “Alzheimer’s disease” or “dementia”; these are merely labels for summaries of observed symptoms. No one gets antibodies to Alzheimer’s; there is no physiological equilibrium-maintaining mechanism like fever as the body’s response to invasive micro-organisms. All this suggests these medical labels are just names we put on the normal process of aging.

All physical things eventually decay; this is an empirical generalization that appears to have no exceptions. When the Buddha lay dying at the age of 80 around 460 B.C., he said that his body was falling apart like an old wooden cart. It has been observed that humans are like automobiles in the following respect: medical expenditures in the last year of life are typically about equal to all previous medical expense; and repair costs of cars ramp up sharply just before they give out entirely. This implies deterioration of the nervous system, like any other deterioration of a living body, is a process wider than life itself.

It may be that the extreme stages of Alzheimer’s are the way that very healthy people die; they live longer because they have not died from cancer, stroke, or heart disease. As cures for common illnesses have improved, there is an increasing residue of persons who live long enough to die of Alzheimer’s.

The medical metaphor of Alzheimer’s as a disease has the further disadvantage of promoting an externally imposed, disease-control policy. What is more relevant is to discover practical methods for living with a fading memory. No doubt everything deteriorates sooner or later, but how long it takes is to some extent under our personal control.

From the grandson of Randall Collins: