The iconic image of January 6 is a protestor sitting with his feet up on Nancy Pelosi’s desk, and another in the Senate Chair. These are reminiscent of Sergei Eisenstein’s 1928 film, October, a documentary of the Russian revolution of November 1917. Attacking the seat of government in Petersburg, the Winter Palace, revolutionary soldiers break into the Czarina’s bedroom: amused by uncovering the jeweled top of her chamber pot, then ripping through her feather-bedding with their bayonets. The same in the French Revolution in its many repetitions between 1789 and 1792, and its replay in 1848, where the crowd took turns sitting on the vacant throne after the guards had collapsed and the royal family had fled.

There are differences, of course. The 1917 and 1792 revolutions were successful in overthrowing the government. The 2021 Capitol assault may have had few such ambitions in the minds of most protestors; and in any case, they occupied the outer steps of the Capitol for five hours and penetrated the corridors and chambers inside for three-and-a-half, with momentum on their side for less than an hour.

The similarities are more in short-term processes: The building guards putting up resistance at first, then losing cohesion, retreating, fading away; some fraternizing with the assaulting crowd, their sympathies wavering. They had weapons but most failed to use them.

Higher up the chain of command, widespread hesitation, confusion, conversations and messages all over the place without immediate results. Reinforcements are called for; reinforcements are promised; reinforcements are coming but they don’t arrive. Recriminations in the aftermath of January 6 have concentrated on this official hesitation and lack of cooperation, and on weakness and collusion among the police.

In fact it is a generic problem. Revolutions and their contemporary analogues all start in an atmosphere of polarization, masses mobilizing themselves, authorities trying to keep them calm and sustain everyday routine. Crowd-control forces, whether soldiers or police, are caught in the middle. At the outset of surging crowds, there is always someplace where the guards are locally outnumbered, pressed not just physically but by the noise and emotional force of the crowd. They usually know that using their superior firepower can provoke the crowds even further. Sometimes they try it; sometimes they try a soft defense; in either case they have a morale problem. If there is a tipping point where they retreat, the crowd surges to its target, and is temporarily in control.

From this point of view, the lesson of January 6 is how protective forces regain control relatively quickly. Comparing the Winter Palace on the night of October 26, 1917* or the Tuileries Palace on August 10, 1792, tells us what makes for tipping points that wobble for a bit but then recover; or not.

* Russia in 1917 was still using the old-style calendar which had been updated by various states of Western Europe during preceding centuries. To convert these dates to the modern international calender, add 13 days to the date. Thus October 26 (old style) becomes November 8 (new style).

The normal exercize of authority is above all a smooth and expectable rhythm. (That doesn’t mean everything goes well, but the hitches are what we are used to.) In revolutions it gets worse and worse until psychological equilibrium is only re-established when one leadership team entirely replaces the other.

The wavering and indecisiveness of the guards and the incoherence of the chain of command higher up are connected. We see this particularly strongly in the Russian and French cases; but the same pattern exists, on a less extreme scale, in the contemporary American crisis. In the weeks and hours leading up to the afternoon of January 6, there are strong splits inside Congress, as well as among the branches of government, not to mention the lineup of states across the federation, and the anomalous local position of the authorities of the District of Columbia. Revolutions and revolts usually begin with prolonged splits at the top, moods which are transmitted to their own security forces. Add to the mix popular crowds which are more than a puppet of elite factions. The energy, enthusiasm, and hostility of crowds has a power of its own (in fact earlier theories of revolution usually focused entirely on this popular force from below). But even granting great causal significance to elite splits, how strong the popular hurricane blows at some point becomes the determining factor of events.

At the tipping point crisis, the two centers of emotional contagion-- the two places the political authority machine can wobble, the crowds-and-cops scene, and the elites quarreling and sending for reinforcements-- are both wobbling at the same time. The outcome depends on which gyroscope rights itself-- if at all.

From this point of view, we will look at the assaults on the Winter Palace in 1917, and the Tuileries in 1792. These were both revolutions from the Left; the Capitol assault of 2021 was from the Right. But the dynamics of crowd confrontation with a center of authority are much the same, regardless of Left or Right ideologies.

Assault on the Winter Palace

The insurgents launched their attempt to take over the capital city on October 25th. The Bolshevik revolutionists had infiltrated and gained the support of most armed forces around Petersburg, units of sailors from ships stationed nearby and soldiers from fortresses and arsenals. Their officers had been arrested or reluctantly came over to the revolution, watched by political committees of their own troops. The Bolsheviks also had a strong base among factory workers and in the railroads and telegraphs, giving them control of communications. Armed workers were now throughout the city carrying rifles and revolutionary flags. Acting together with the troops on the first day of the insurrection, they took over most of the major buildings and installations in the city: the railroad stations, bridges across the river, the electric plant, banks, government offices-- all except the Winter Palace.

It was the former palace of the Czars, now occupied by a coalition government of liberal reformers and former officials, since the Czar had abdicated in February. Here was concentrated what military forces the government still had in the capital city. Here they waited and sent out messages for reinforcements to put down the revolutionaries: recalling troops from the front against the Germans; Cossack cavalry long dreaded as the enforcers of the absolute monarchy; elite military units recruited from the respectable middle class; students from the military schools. The Winter Palace was the military stronghold and political command center; the center of political legitimacy, too, since it housed the Assembly that made the laws and the Ministry that made official decisions. As long as the Winter Palace held out, the revolution hung in the balance.

On the 26th, the Bolsheviks got their forces in a ring around the Winter Palace and began to close in. Both sides proceeded cautiously.

“The court of the palace opening on the square is piled up with logs of firewood like the court of Smolny [the building across town where the Bolsheviks have their meetings]. Rifles are stacked up in several different places. The small guard of the palace clings close to the building... Inside the palace they found a lack of provisions. Some of the military cadets did sentry duty; the rest lay around inactive, uncertain and hungry. In the square before the palace, and on the river quay on the other side, little groups of apparently peaceful passers-by began to appear, and they would snatch the rifles from the sentries, threatening them with revolvers...” [Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, 387-8] Agitators also began to appear among the cadets, internal trouble-makers; they quarrel about who they should take orders from, the civilian ministers or their own school directors. They opt for the latter--severing the chain of command. They take their posts but are forbidden to fire first.

Outside on the river bank, thousands of soldiers and sailors are being disembarked who have gone over to the insurgency. Their remaining officers “are being taken along to fight for a cause which they hate.” The Bolshevik commissar announces: “We do not count upon your sympathy, but we demand that you be at your posts... We will spare you any unnecessary unpleasantness.” The most militant of the troops volunteer for action on their own. “The most resolute in the detachment choose themselves out automatically. These sailors in black blouses with rifles and cartridge belts will go all the way.” [390] The take-over of the city had mostly been by military units acting in regular order, encountering virtually no resistance, the token forces of the government letting themselves be disarmed. A real fight now looms ahead. The militants of armed workers meld with militants of the troops in a crowd-like surge.

“Hiding behind their piles of firewood, the cadets followed tensely the cordon forming on Palace Square, meeting every movement of the enemy with rifle and machine gun fire. They answered in kind. Towards night the firing became hotter. The first casualties occurred. The victims, however, were only a few individuals. On the square, on the quays, the besiegers hid behind projections, concealed themselves in hollows, cling along walls. Among the reserves the soldiers and Red Guards warmed themselves around campfires which they had kindled at nightfall, abusing the leaders for going so slow.

“In the palace the cadets were taking up positions in the corridors, on the stairway, at the entrances, and in the court. The outside sentries clung along the fence and walls. The building would hold thousands, now it held hundreds. The vast quarters behind the sphere of defense seemed dead. Most of the servants were scattered, or in hiding. Many of the officers took refuge in the buffet... The garrison of the palace was greatly reduced in number. If at the moment [of greatest reinforcement] it rose to a thousand and a half, or perhaps two thousand, it was now reduced to a thousand, perhaps considerably less... With angry and frowning faces the Cossacks gathered up their saddle bags. No further arguments could move them...The Cossacks were in touch with the besiegers, and they got free passes through an exit till then unknown to the defenders. Only their machine guns they agreed to leave for the defense of a hopeless cause.

“By this same entrance, too, coming from the direction of the street, Bolsheviks before this had gotten into the palace for the purpose of demoralizing the enemy. Oftener and oftener mysterious figures began to appear in the corridors beside the cadets. It was useless to resist; the insurrectionists have captured the city and the railway stations; there are no reinforcements... What are we to do next? asked the cadets. The government refused to issue any direct commands. The ministers themselves would stand by their old decision; the rest could do as they pleased. That meant free egress from the palace for those who wanted it. The ministers passively awaited their fate. One subsequently related: “We wandered through the gigantic mousetrap, meeting occasionally, either all together or in small groups, for brief conversations... Around us vacancy, within us vacancy, and in this grew up the soulless courage of placid indifference.” [394-6, 401]

Artillery from the ships fired sporadically, the gunners unenthusiastic, hoping for an easy victory. Of 35 shells fired in a couple of hours, only 2 hit the palace, injuring the plaster. [400]

“The inner resolution of the workers and sailors is great, but it has not yet become bitter. Lest they call down it on their heads, the besieged, being the incomparably weaker side, dare not deal severely with those agents of the enemy who have penetrated the palace. There are no executions. Uninvited guests now begin to appear no longer one by one, but in groups. The palace is getting more and more like a sieve. When the cadets fall upon these intruders, the latter permit themselves to be disarmed... These men were not cowardly; it required a high courage to make one’s way into that palace crowded with officers and cadets. In the labyrinth of an unknown building, among innumerable doors leading nobody knew where, and threatening nobody knew what, the daredevils had nothing to do but surrender. The number of captives grows. New groups break in. It is no longer quite clear who is surrendering to whom, who is disarming whom. The artillery continues to boom.” [403]

The siege began in earnest about 6 p.m. With periodic excursions and lulls, it went on until 2 a.m. Lenin and the Bolsheviks at their headquarters are getting anxious, sending angry notes for all-out artillery fire. The commander decides to wait another quarter hour “sensing the possibility of a change in circumstances.” Time is almost up when a courier arrives: The palace is taken!

“The palace did not surrender but was taken by storm-- however, at a moment when the power of resistance of the besieged had already completely evaporated. Hundreds of enemies broke into the corridor-- not by the secret entrance this time but through the defended door-- and were taken by the demoralized defenders for a deputation [of supporters]. A considerable group of cadets got away in the confusion. The rest-- at least a number of them-- still continued to stand guard. But the barrier of bayonets and rifle fire between the attackers and the defenders was finally broken down.” They are now confronting face to face-- psychologically the most difficult situation for effective use of weapons.

“Part of the palace is already filled with the enemy. The cadets make an attempt to come at them from the rear. In the corridors phantasmagoric meetings and clashes take place. All are armed to the teeth. Lifted hands hold revolvers. Hand grenades hang from belts. But nobody shoots and nobody throws a grenade. For they and their enemy are so mixed together that they cannot drag themselves apart. Never mind: the fate of the palace is already decided.

“Workers, sailors, soldiers are pushing up from outside in chains and groups, flinging the cadets from the barricades, bursting through the court, stumbling into the cadets on the staircase, crowding them back, toppling them over, driving them upstairs. Another wave comes on behind. The square pours into the court. The court pours into the palace, and floods up and down stairways and through corridors. On the befouled parapets, among mattresses and chunks of bread, people, rifles, hand grenades are wallowing.

“The conquerors find that Kerensky [head of government] is not there, and a momentary pang of disappointment interrupts their furious joy... Where is the government?”

They have long since abandoned the great assembly hall overlooking the river now full of gunboats. They have retreated to an inner room, as far away as possible. “That is the door-- there where the cadets stand frozen in the last pose of resistance. The head sentry rushes to the ministers with a question: Are we commanded to resist to the end? No, no, the ministers do not command that. After all, the palace is taken. There is no need for bloodshed. The ministers desire to surrender with dignity, and sit at the table in imitation of a session of the government.” [403-4]

The last guards are disarmed. The door crashes open. Backed by the crowd, the Bolshevik commissar takes the ministers’ credentials and declares their arrest. The officers and cadets of the defense are allowed to go free. As the ministers are led away through square, there are shouts: “Death to them! Shoot them!” Some soldiers strike at the prisoners. The commissar and the Red Guards stick to the ritual of victory, escorting the overthrown authorities to prison, an act of taking their place.

Physically these scenes at the Winter Palace look a lot like the Capitol in January 2021: Both buildings are labyrinths, huge complexes of assembly chambers, galleries, halls, stairwells, meeting rooms, offices. There are tunnels, secret passages, escape routes, hidden doors. There are main entrances, back entrances, side entrances. Especially when some people are evacuating and others intruding, there are plenty of mix-ups; sometimes crowded clashes, standoffs with barely room to swing about; sometimes guards or protestors, one side or another, find themselves outnumbered; sometimes-- as we see in photos-- lone protestors striding through grand spaces with their flags or booty; sometimes arrestees sprawled on the floor under guard, sometimes a thin line of guards backed up against a door. Both attackers and defenders are swallowed up by the building, forces stretched thin and unable to be everywhere at once. Both sides are uncertain, confused, without chains of command on the spot; unclear what is behind a door, who has what weapons, how our forces are holding out or making inroads; how many are smashing through openings and preparing to rush inside. Members of Congress hunker down in the rows between the seats, and are led away by security forces to subterranean hallways, take refuge in a basement cafeteria like the Russian officers hiding in the buffet. Some attackers wander about in remote corridors; in 2021, getting into Congressional offices, taking selfies, rifling through desks. In 1917, Russian militants and defender cadets alike fill their pockets with expensive knick-knacks from the sprawling palace. Some are fighting; many are not. We will come back to the points of violence.

To summarize the pattern, so confusing in detail and lived experience, let us invoke the tottering gyroscopes of organization in varying levels of breakdown: first the point of view from below on the front lines, then the view of chains of authority from above. Start with 1917; then 2021.

Wavering among government forces: We have seen the Winter Palace guards, heavily armed but mostly tired, bored and discouraged. Sometimes they let their guns be taken away from them. Sometimes they fire across the courtyard, mostly missing (not unusual in the sociology of combat). Sometimes they are ordered not to fire first-- but who can tell who starts it? Their sympathies are not at all with the revolution; they are elite military cadets, although going into action for the first time. Nevertheless the mood and pressure of the situation determines whether they fire or not. They have moments of hope; the enemy is holding back, maybe they too are experiencing difficulties, maybe help is on its way.

The hardened Cossacks, an alien ethnic group amid the Russian population, used for administering whippings and massacres to uphold authority, are expected to be the bulwark of the defense. But now they hesitate. They will obey orders to support the Winter Palace; but-- first they need assurances they will not be alone, there should also be infantry, artillery, armored cars. The government assures them these will be there. In fact they are not; Cossacks get wind of it, or suspect it. They are preparing to move-- telephone messages go between barracks and Palace-- but they don’t move. A few Cossack units reach the Palace; after assessing the situation, the atmosphere, the lack of chain of command, they negotiate with the besiegers a retreat through a secret exit.

And so it goes with reinforcements from the front. The government wants to send unreliable units out from the capital, and bring back reliable units. But ministers can talk only to officers who are their sympathizers, or at least their yes-men. Chains of command are poor in the army as well; and the railroads are not under their control. Within the military units we know most about, mainly the naval forces who have mutinied to the Bolsheviks or have cowed their officers into going along with them, there remains hesitation about using force. Artillery assault is called for; but the gunners complain their guns are not ready; when they finally fire, it seems they don’t want to hit anything, hoping the situation will resolve itself. They are holding open their options, waiting to see which side is going to lose.

Wavering among government politicians: The government is not set up to act with decisiveness, for it is a coalition of hold-overs from the czarist regime and a variety of parties of differing ideologies and militancy; of those who took part in the February revolution and those who resisted it. This is particularly true in the military side of the administration; the government is now calling on its old enemies to defend it. Meetings in the Winter Palace agree on little except resisting a second revolution, but even here politicians are split between those who demand a vigorous crackdown and those who want a softer policy of conciliation. It all depends on how much of a show of force they can muster, but this boils down to putting up a frontstage of optimism that reinforcements are on their way. They waver between optimism and pessimism. Discussions and arguments take place over the telephone, making demands to military headquarters, to citizens militias, to Cossack regiments, to the military schools.

Moments of optimism come from the confusion of communications, and indeed the confusion of events themselves. To the extent there is any chain of command, the government ministers are talking with high officials whose own authority chains are out of order. Some talk a good show; they are willing to put down the insurrection, if only they can get some coordinated support. Others become increasingly exasperated; I agree with your orders, Minister, but where are the troops to carry them out? Sometimes the revolutionaries can’t seem to get their act together either; with every lull and delay optimism of the defenders goes up a notch. It it not a bandwagon-- yet. How long can the indecisiveness last?

Wavering among the revolutionaries: Generically, their problems are similar, but quantitatively better. Their forces on the ground are a mixed bag; some ideological militants; some newly joined allies in the navy and army; old-line officers of dubious loyalty; many holding back to see what will happen. Politically, too, the left-wing assembly and the local soviets (councils) are coalitions, not just Bolsheviks but other factions and splits left over from 15 years of revolutionary politics. On present policy, the divisions are among those who want to press their advantage right now, and those who are cautious, worried, or hoping for a peaceful transfer of power. Lenin, Trotsky and their faction want to present the waverers with a fait accompli, and that means taking the Winter Palace before it is reinforced. Emotionally, they have a recent bandwagon in their favor, the successful take-over of the city the previous day.

But a bandwagon has to keep moving to new adherents and new successes; if it stalls, the mood starts flowing away. The militants are mobilized; they must be put into action against the final target. But realistically, there are logistical and organizational problems to work out. Plans to use their military supporters to surround the Winter Palace, to bring combined arms into action-- all these are too complicated for a newly improvised structure. And in any case, this is counting too much of organization from the top. Their biggest resource at the moment is the spontaneity of the self-propelling crowd. The Bolshevik network is capable of getting the most militant workers and sailors on the spot, if with enough lags and delays to give hopes to the defenders. At this point a crowd surge develops. Intersecting with the mood inside the Winter Palace, the tipping point tips.

Top-down and bottom-up

Enthusiastic self-mobilizing crowds, and the strategies of political elites, play into each other. Politics in normal times is almost entirely the province of political elites. But when crowds repeatedly mobilize themselves with their own indigenous networks and organizations, they become social movements with momentum and tactics of their own. Such movements can change the career trajectories of politicians, on the whole more than vice versa. The world history of labor movements, or of racial/ethnic movements, give ample evidence of this.

If we need recent examples of how energized crowds carry politicians along pathways with a vehemence they may not have anticipated, consider how Bernie Sanders’ campaign in 2016 ballooned from token opposition to serious challenge to Hillary Clinton; Trump’s discovery that his reality-TV methods generated such crowd enthusiasm that he kept feeding off of rallies throughout his 4 years in office; the Black Lives Matter demonstrations in spring and summer 2020, creating a political bandwagon whose stronghold became the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives. And which became the target for the counter-mobilization culminating in the January 6 assault. Trump’s emotional addiction to rallies took him down the slope of political psychosis, the delusion that the size of his crowds meant he couldn’t possibly have lost the popular vote-- a delusion shared by the rallies themselves.

There is always a danger, as a sociologist, of being emotionally too close to an event to see what is going on, what the patterns are and the relative weight of the various forces. Our ideological labels, Left and Right, don’t help. We have seen enough of Petersburg in 1917 to recognize the most general features of Washington in January 2021. But we have to abstract away from the particular names and issues, to get at the dynamics. If the Presidency is on their side, can the attackers at the Capitol be a revolution, or a counter-revolution, or a coup? Or is it Smolny Institute against the Winter Palace again? Better to invoke the imagery of two spinning gyroscopes, tottering or staying upright. From this perspective, attacker and defender are subject to the same dynamics, differing only quantitatively. Look at who wavers when and how much:

Wavering among official forces at the Capitol:

It needs to be appreciated that many different officials and organizations had a role in the defense of the Capitol, with no command center. Advance intelligence about possible attacks by militant groups and unorganized protestors came from the FBI, military intelligence agencies, and civilian organizations like the Anti-Defamation League. These differed widely on how seriously on-line rhetoric about violence should be taken. Advance estimates of the crowd size to be expected ranged from 2,000 to 80,000.

Forces that could be brought into action included: (a) the Metropolitan Police of the District of Columbia, reporting to the Mayor; (b) the Capitol Police, under a Police Chief, as well as a Sergeant-at-Arms for the House of Representatives, and another Sergeant-at-Arms for the Senate; these latter reporting to the Speaker and Majority Leader; (c) the Secret Service, armed plain-clothes officers protecting not only the President but all those in the chain of succession, notably the Vice President and Speaker of the House; (d) other federal officers, including FBI SWAT teams, Dept. of Homeland Security, and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives; (e) US military forces under the Secretary of Defense; the US Army specifically under the Secretary of the Army; (f) the National Guard forces of each state, which can be deployed under orders from each Governor, although coordinated with the Secretary of the Army; (g) the National Guard of the District of Columbia, which not being a state, could only be called out by the President. Altogether these make up at least 15 quasi-autonomous officials and agencies (not counting the 50 state Governors and National Guards). The array gave plenty of room for communication and coordination problems, not to mention differences in policy and partisan splits-- not least with President Trump urging on the protestors and resisting mobilizing Federal forces. Chains of command were sometimes upheld, sometimes breached.

To sample these disagreements: Washington D.C. Mayor on December 31, 2020 (7 days before the Electoral College count) requested calling out the D.C. National Guard, but only to provide unarmed crowd management and traffic control; this was approved by the Acting Secretary of Defense on January 4, calling up 340 troops but no more than 115 at a time. There must have been splits in the Pentagon, since on Jan. 3 some officials offered the National Guard; but Metropolitan Police Chief said later they had no intelligence that the Capitol would be invaded, and Capitol Police Chief said it would be unnecessary. The latter had 2000 uniformed cops, but assigned only normal staffing levels (ordinarily there are 4 40-hours shifts per week, so the number available would be about 500, minus administrative personnel). Accustomed to dealing with tourists and peaceful protests, they counted on a soft, friendly style to keep the crowd in hand. The Capitol Police Chief also said he didn’t like the impression it would give if armed troops were photographed around the Capitol; a sentiment echoed by some military officials.

Once the attack began, disagreements persisted for a while over how severe the breach was. Around 1 p.m., when hundreds of rioters pushed aside barriers and climbed to the higher terraces outside the Capitol, the House Representative chairing the Committee in charge of security called the Capitol Police Chief but couldn’t get through; the House Sergeant-at-Arms, assured her that the doors are locked and no one can get in. Shortly after, Capitol Police Chief (who was not on site but at his headquarters) called the House and Senate Sergeants-at-Arms for emergency declarations from their respective chambers to call the National Guard; they replied they would “run it up the chain” of command. The Democrat-controlled House side got their approval about an hour later, after windows and doors were broken in and rioters entered the building. On the Republican-controlled Senate side, the Sergeant-at-Arms apparently never did notify the leadership. Rioters reached the Senate around 2.15, just after its doors were locked. At the same time, the House recessed briefly when Secret Service escorted the Speaker out; but resumed debate again at 2.25-- apparently thinking the disturbance was minor. They recessed for good at 2.30, as rioters noisily banged on the doors.

By this time the Capitol Police Chief in a conference call urgently requested National Guard “boots on the ground”. The conversation was described as chaotic as everyone asked questions at the same time. The General directing the Army Staff resisted, arguing “I don’t like the visual of the National Guard standing a police line with the Capitol in the background,” and that only the Secretary of the Army (who was in different meeting) had authority to approve the request. Finally at 3 p.m. the Secretary of Defense authorized deploying the 1,100 troops of the D.C. National Guard, but restricted from carrying ammunition and sharing equipment with police without prior approval. Since Trump resisted the order, Pence approved it on his own authority, breaking the chain of command.

In the event, it did not make much difference. Metro police sent 100 reinforcements within 10 minutes after the police line was pushed back at 1 p.m. The D.C. National Guard mobilization would take at least 2 hours for its members to assemble and get equipped at the D.C. Armory. In fact, 150 troops arrived at the Capitol at 5.40, just as the Capitol Police announce the building has been cleared of rioters. Meanwhile, between 2.30 and 2.50, calls from D.C. Mayor to the Virginia State Police promised reinforcements, the first of which began arriving in the city at 3.15; while a request for the Virginia National Guard was authorized by the Governor but not by the Defense Dept. About 3.40 Maryland Governor ordered mobilization in anticipation of a request, which comes from the General in charge of the Pentagon National Guard Bureau about 4 p.m. But Maryland National Guard forces are not expected until next day. At 5 p.m. New Jersey Governor announced he was sending state police at request of D.C. officials; and in the evening New York Governor said he would send 1000 National Guards.

The invasion of the Capitol building itself lasted from about 2.10 to 5.40 p.m., the Senate having been invaded for only a few minutes around 2.30, and the House repelling an attack at 2.45 when one rioter is shot and killed by plain-clothes security. By 3 p.m., many people who entered the House side of the building were leaving. On the Senate side, clashes continued until after 4 p.m.

By this time the mostly unarmed Capitol Police were reinforced by ATF tactical teams, and by SWAT teams of the Metro Police in heavy gear. Other buildings in the Capitol complex, including the Senate Office Building were cleared by FBI and Homeland Security forces in riot gear around 4.30 p.m. At 6.15, the Capitol Police, Metro Police, and DC National Guard had formed a perimeter around the Capitol, although several hundred rioters remained in the vicinity until around 8 p.m.

The promised reinforcements were mostly psychological in effect, building confidence among the victors. On the front line, the Capitol Police had put up a delaying resistance, taking about 60 casualties (15 seriously enough to be hospitalized), with one dead. The Metro Police had 56 injuries. The rioters apparently got off easier, 1 killed by gunfire, 5 rioters known to be hospitalized: out of perhaps 300-500 who breached the Capitol, and the thousands (10,000?) who shouted support outside. Among these latter, 3 died of heart attacks or other emotional effects of extreme excitement. The shooting was done by a Capitol Police lieutenant, which appears to have turned the tide. Heavily armored SWAT teams effectively mopped up die-hard resistance.

[sources: Associated Press; Wall Street Journal; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; published and on-line photos and videos.]

Police lines retreat, violence, and crowd management

Police retreated in two phases on the West (main) front of the Capitol; another sequence at the East (rear) of the building involved a smaller crowd and fewer police. On the East side, a crowd started gathering around 12 noon. On the West side, a larger crowd gathered by 12.30. By 12.53, the crowd began to push back police from barricades of waist-high portable fencing. (My counts from photos indicate about 2500 people visible in the crowd-- with more further back and on the wings; against a single line of about 80 police behind the fencing, with somewhat less than that number spread out in the space behind them.) Over the next 10 minutes, the crowd overran three more rows of barricades, the officers retreating to the base of the Capitol steps. Photos and videos of this phase show what looks like a tug of war, 3-or-4 men on each side of a segment of fencing, which they push to tip over or hold upright. Occasionally someone on either side rushes forward to strike across the barrier with baton or stick. The cops are trying hard, pushing back vigorously.

Around 1.30, a large crowd arrives from listening to the Trump rally 14 blocks away. This increases the density of the crowd pushing the police up the steps to the Capitol terraces. But on the whole, there is an hour-long standoff, lasting from 1 to 2 p.m., until the break-in to the building itself.

Meanwhile on the East side, a smaller police line loses control of the last barrier at 2 p.m. Information is lacking on when this crowd got inside, but they must have added to the chaotic situation of intruders in the corridors and tunnels of the Capitol building complex. They probably also were those who entered other nearby buildings including the Senate office building, and breaking into and ransacking offices inside the Capitol complex that went on for several hours after the main assault crowd from the West front was dispersed.

Shortly after police lines of the East side collapsed, on the West front about 2.10 p.m., police are pushed up the grand steps. The emotional momentum is with the crowd, who break through a side door and window at 2.12 and are inside. Within a few minutes they on the second floor outside the Senate chamber. Videos show a lone cop rather coolly engaging a dozen intruders, gesturing at them, turning to climb a stairwell, looking back to make sure they are following; he has a pistol in his holster but never reaches for it. The intruders advance surprisingly slowly, hardly more than brisk walking pace; the cop misleads them away from the doors of the Senate. Alerted security locked the Senate doors at 2.15, a minute before intruders reached the gallery outside the chamber. The Senate was evacuated by 2.30, before some attackers briefly got into the viewer’s gallery, and few climbed down to sit in the presider’s chair and pose for photos.

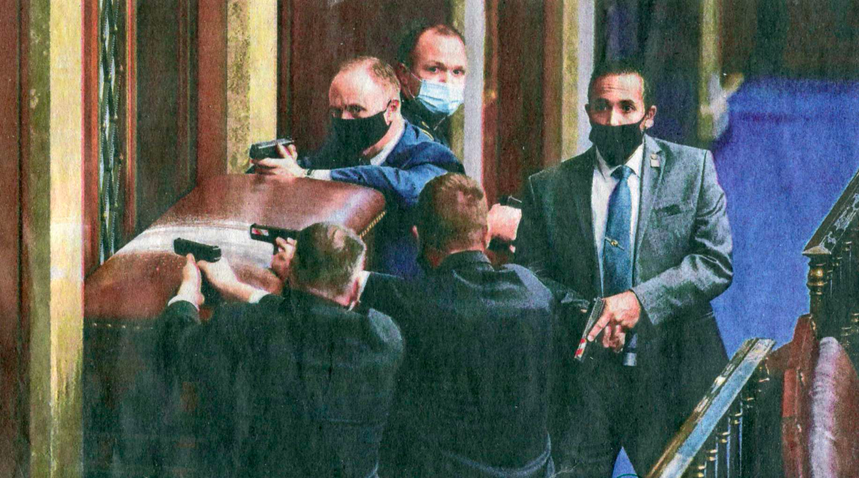

Meanwhile, most of the crowd moved through the Rotunda into the House wing around 2.30 (the Representatives started evacuating after 2.20). As they pounded on the doors shouting to find Pelosi, a group of about a dozen followed a side corridor to reach a windowed door into the Speaker’s lobby, near a staircase used just before to complete the evacuation. Videos show them arguing with three police who rather calmly guard the door; they wear no helmets or riot gear, and pass the word they are being relieved by a heavily armored tactical squad. In the two minutes when the police withdraw to make room for their reinforcements, the mob pounds on the door, shouting and breaking the windows in the upper doors with a helmet, fists and stick. Meanwhile, photos taken from the inside of the House chamber itself show five plain-clothes officers in suits, behind an improvised barricade of furniture, aiming handguns at the main doors where the crowd is clamoring to get in. These are not the same as the officer in the lobby at the rear of the House, who shot and killed Air Force veteran Ashli Babbitt, climbing through the broken door window at 2.44 pm. It was the last peak of momentum of the attackers.

Calm cop, gun holstered

On the whole, there is little evidence of panic among the police; they put up a strong resistance at each barricade outside the building until pushed back by crowd pressure. Inside, photos and videos show the police largely calm. The greatest tension is in the faces and body postures of the police getting ready to fire if the House door is breached.

Capitol police point guns at House door

Other photos show the most intense emotions at moments when the Rotunda is crowded with both sides mixed together: police in riot gear--helmets with plastic visors-- rioters in MAGA hats, hockey helmets, stocking caps, bare-headed, a few flags visible and more than a few mobile phones taking pictures. My count gives about 150 persons pushed together at close quarters, approximately equal numbers of both sides. In the distance along the far wall, we can see about 50 cops lined up in riot gear; the impression is they are held in reserve, as the tide has turned and the rioters are being driven into retreat. There are more cops than rioters in the foreground.

Melee in the rotunda

How violent was it? Although news reports noted that rioters had guns and explosives, this seems to be based mainly on discoveries away from the Capitol: home-made pipe bombs at the Republican National Committee and Democratic National Committee headquarters. A street search found a parked vehicle with a handgun, assault rifle, ammunition, and homemade napalm bombs.* These reports raised alarm in the Capitol, and spread the belief that the rioters, including the one who was shot and killed in the House lobby, were an armed threat. Except for that shooting, the weaponry used on both sides was surprisingly low-level. The Capitol police had a considerable arsenal at their disposal, but initially the officers inside the building were in regular uniform; those at the barricades outside were in riot gear, with helmets, shields and batons. Within an hour after the breach, photos show forces inside mostly in riot gear.

* This home-made arsenal is similar to those accumulated by school rampage shooters obsessed with a private cult of accumulating weapons, few of which they actually use. Collins, Clues to Mass Rampage Killers.

Some rioters wore a version of riot gear, helmets, military-style vests. These were prominent among the dozen or so who scaled the West front of the Capitol to reach the top terrace. This appears to have been showing off, since photos show the crowd was already up the side steps and behind the police lines. It may well be that the most heavily equipped rioters were either police or military personnel (current or former), including ideological militias. In fact they seemed to believe they were taking part in a legitimate police mission of their own, carrying plastic handcuffs to arrest “traitors”. But their “weapons” were more in the nature of accoutrements; handcuffs are not offensive weapons, although strongly identified with cops; similarly with the two-way radios some carried; and with reports of “stun grenades”, what SWAT teams call “flash-bangs” used to confuse a hostage-taker, which is to say a device to avoid using lethal violence if possible.

The rioters’ main high-tech offensive weapon was “bear spray”-- high-intensity pepper spray used as protection against wild animals by outdoor campers and hikers. It is unclear how often or in what situations it was used.* What is most in evidence are flag poles (doubling as emblems), and sticks, chiefly used to break windows.

* The only photo I have seen among several hundred posted is of a young man in helmet and gas mask, outside at the base of the Capitol, who sprays a brown liquid across an empty space in the crowd while running with his head turned the other way. This was probably around 12.50 p.m. when the crowd first surged against police lines. There are several photos of police spraying a clear liquid at protestors, in these external scenes.

One of the most violent incidents of which we have a description took place during the peak moment of conflict outside the West front, when the crowd found a relatively lightly guarded side door where they eventually broke in. Three cops were pulled out of the defensive line (to make room for the attackers), and shoved down the steps. Cut off from support and surrounded by a large crowd, they were beaten with “hockey sticks, crutches, flags, poles, and stolen police shields”-- on the whole, improvised weapons. In the sociology of violence, this is called a “forward panic,” where a group that has been in an intense confrontation suddenly finds the balance has broken, one side is suddenly at the mercy of the other, and an emotional surge of adrenaline takes over and results in a beating characterized by piling on and overkill. [Collins, Violent Conflict] Unlike in most military and police-chase situations, here the victims escaped alive-- the difference being, no one had guns.

The most serious casualties caused by the attackers were from improvised weapons found on the spot: fire extinguishers. One incident happened, again at the flashpoint on the West front, after 2 p.m. as the police line was breached. [Wall St. Journal Jan. 15, 2021 A6] The attacker, retired from a Philadelphia-area fire department, threw a fire extinguisher at the police line, hitting three officers in the head (one of them not wearing a helmet). That officer was evaluated at a hospital and returned to duty. This was a separate incident from the one inside the Capitol where a police officer was killed. Apparently during a struggle in a crowded corridor, Officer Brian Sicknick was knocked down or hit from behind on the head by a fire extinguisher. Although details are lacking, this is in keeping with the typical pattern in deadly violence: no eye contact when the attack is made. The same is the case with Ashli Babbitt, who was unarmed, but the officer who shot her was at the climax of a tense situation, the House Chamber about to be invaded, a noisy threat outside the door, then a sudden intrusion right at the gun tensely held by both hands pointed at the entry window. In the sociology of violence, close face-to-face confrontations are emotionally stressful on both sides, pumping adrenaline to the level where most participants are incompetent with their weapons, unable to fire accurately; perceptually, it becomes a blur. A minority of highly trained soldiers and police control their adrenaline enough to pull the trigger under such situations; an even smaller minority hit their target.

The most striking thing about the violence at the Capitol is that so little of it came from gunfire. Many hundreds of police on the scene had guns; except at the climax of the attack on the House, none were fired, and few were drawn or aimed. A rare photo of 5 captive rioters shows them lying prone on the floor, guarded by 3 cops with a baton but guns holstered. On the side of the protestors, 5 guns were seized, although it unclear if these were inside the Capitol-- if so, they were never used. Sociologically, this is neither amazing, nor is it a point in anyone’s favor or fault: it is the most typical pattern of armed confrontations. Whether by police, gangs, robbers, or military in combat, in the vast majority of confrontations with guns, they are not used.

Victory or defeat, advancing or retreating, is far more emotional and psychological than physical violence itself. This pattern holds too at the Capitol, as it does in 1917 and 1792.

Fraternization

Fraternization between protestors and regime forces has played a major part in any successful revolution. In Russia in 1917, agitation by Bolshevik sympathizers inside the army and navy prepared the way by bringing them over to their side; and it was these militants and the most convinced sailors who made the attack on the Winter Palace. And in the early hours of the attack, agitators inside created confusion and promoted the defection of most of the defending troops. There are numerous examples of this pattern. The downfall of the Soviet Union was consummated in August 1991 when tanks sent to take over the parliament building were surrounded by crowds, and Boris Yeltsin climbed on top of a tank to take command from its stunned and demoralized crew. In the most famous of the Arab Spring revolts in 2011, crowds in Cairo’s Tahrir Square chanted “the army and the people are one hand” as security forces first refused to expel the protestors, then changed sides to protect them against last-ditch attacks by Mubarak’s militia enforcers.

Armed forces swinging over in a tidal wave happens when two conditions hold: when rebellion appears right and just to a vast majority of people (maybe just those who are most visible in the capital city); and when it seems inevitable, making it dangerous to hold back. The first of these conditions existed to a degree at the Capitol; the second hardly at all.

The attackers certainly made efforts at solidarity with the police. Reportedly some rioters showed police badges or military IDs as if expecting to be allowed inside. A Capitol police officer said one rioter displayed a badge and said “we’re doing this for you.” Some intruders wore the “thin blue line” emblem of support for the police. Some videos showed police standing back and allowing rioters into the building; one officer was seen in a “selfie” with a rioter inside the building. Especially inside, where during the initial phases the police were not in riot gear, police tended to maintain normal demeanor and to talk quietly with the intruders. Afterwards, some Representatives accused the police of complicity, including giving them directions to specific offices, or giving them preliminary tours of the layout. Two Capitol police were suspended and ten or more were under investigation. One officer committed suicide.

The police were also criticized for making very few arrests (about 30 on the Capitol grounds, mostly outside), and for letting the hundreds of intruders get away once control was regained after 3 p.m. In fact, it appears the police were most concerned to clear the Capitol, and the most expeditious way to do it was to push or lead them out the doors. Making arrests is like taking prisoners in a battle; it is the most honorific protocol, but prisoners take up manpower to guard them. Bear in mind that all this happened before reinforcements started arriving at the Capitol about 6 p.m. Most of the arrests that did happen were apparently outside in the evening, when a large number of police chased down the die-hards from the demonstration.

Most of this behavior was ambiguous. One gets the impression from watching videos made inside the building that the officers not in battle dress tried to maintain as much of an atmosphere of normalcy as possible. In the initial phase of entry, the intruders once inside walked rather tentatively, not rushing about in a frenzy but even staying inside velvet guide ropes set up for tourists. Photos in this phase generally showed thin numbers spread out in a lot of space; police presence in the halls and Rotunda was sparse or non-existent.

Thin numbers in the East Wing

Riot-equipped forces were concentrated outside, while tactical squads in riot gear, visible in later photos, had not yet mustered inside. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising the cops were not interested in putting up violent resistance. The exception, of course, was when the intruders reached their goal-- the legislative chambers themselves; above all at the doors of the House, the only place where guns were drawn, and used. And these were the places where the crowds grew most agitated, shouting threats and slogans and trying to smash their way in.

Current or former police officers and military personnel were prominent in the front lines pushing back the barricades, and among those who got inside. Later investigations concentrated on persons identified by photos and videos or their own on-line posts; among these about one-fifth of the hundred or so investigations were police or military. Most prominent of all was Ashli Babbitt, veteran of many deployments in Iraq, who was a security officer (i.e., military police) in the Air Force.

Two comments: first, it is typical in riots that the great majority of the crowd are onlookers and noise-making supporters; only about 10 percent or less of the persons seen in riot photos are actually doing something violent, engaging the other side. It may well be the case that those who carry the battle are specialists in violence, as Charles Tilly calls them, tough guys, athletes and weapons specialists on either side of the law. (One of those charged at the Capitol was an Olympic gold-medalist swimmer.)

Second: in the overall context of recent years and months, it is not surprising that some substantial portion of American police, as well as military, are disgruntled. Among veterans and active-duty military, the suicide rate has been at a peak; the psychological toll of fighting for almost 20 years in seemingly endless wars in the Middle East; a professional (non-draftee) force repeatedly deployed, isolated from the majority of the home population; wars where victories repeatedly proved temporary and reversible; and where news publicity concentrated more on atrocities against the enemy than on American accomplishments. Since a substantial portion of police are veterans (the job where their training is most relevant), there is a bond of sympathy between the two occupations.

The police themselves have experienced the historically strongest wave of criticism in the media and from liberal politicians. Starting in the 1990s when amateur video of violent police arrests became publicized, protest has accelerated with the proliferation of mobile-phone cameras, CCTV, and near-instantaneous propagation through the Internet. Police shootings and violent arrests have resulted in a series of protest demonstrations nationwide periodically dominating the news cycle since Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, Baltimore in 2015, and others. The most intense protests were those starting in late May 2020, in the midst of dissention over the COVID shut-down; these were the most widespread and long-lasting ever, extending into September and beyond in hot spots such as Seattle and Portland. More than in any previous protests, most news media supported these Black Lives Matter protests and related actions; publicizing and endorsing their calls to defund the police; blaming local police for racism; blaming violence on Federal intervention by the Trump administration; downplaying arson and attacks on police stations, courthouses, and government buildings. Many police felt they were being unfairly blamed for the actions of a few, with little understanding for doing a tough job in a period of sharply rising homicide in minority neighbourhoods.

In the context of an election campaign, both parties rallied to the issue: Democrat politicians on the whole endorsed BLM demands for whole-sale revision not only of policing but the historical legacy of slavery and racism. A wave of tearing down Civil War statues of Confederates expanded into renaming and expunging almost anyone in US history who could be implicated in slave-holding, words or deeds detrimental to Native Americans, or European settlement of North America in general. These included Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses Grant, and Teddy Roosevelt. In June 2020, in the midst of the protests over the death of George Floyd, the Democrat controlled House of Representatives voted to change the District of Columbia into a state renamed Douglass Commonwealth, replacing Christopher Columbus with the abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Corporations were pressured into re-education programs at which employees were told to avow their guilt in being white.

Conflict moves by escalation and counter-escalation. Social movements on both sides mobilized from below; politicians attached themselves to the emotional momentum. An attack, both verbal and physical, on the police led to counter-mobilization. Some of it built upon existing right-wing militias and conspiracy-publicists, gaining recruits to the Proud Boys and others who took the defense of the police installations into their own hands. A strange coalition of extremists and police was created, at least in goals and sympathies, which only became manifest in the assault on the Capitol.

This was the atmosphere in which Trump supporters, polarized against the BLM protests, the left-dominated media, and the congressional Democrats, acquired the emotional conviction that their country was being taken from them. The slogan of the stolen vote was a symbol of this larger feeling. Trump fed it with his rallies, ritualistic emotional-energy generators that swing belief into line with a surge of collective feeling. The Durkheimian collectivity always feels like we are Society, we are the People; it is not quantitative but embodied and totalistic. Riding this emotional wave, they swarmed the Capitol. The effort to fraternize with the Capitol police came out of this conviction.

But a Durkheimian political groundswell must be overwhelming; it reaches its nemesis when there is a counter-mobilization on the other side. Two wavering bodies, with their usual disorientation and lack of smooth coordination at moments of crisis, do not create the ingredient that sways the behavior of security forces at the hinge of events: the feeling that revolution is inevitable, better to join it than be left in the minority opposing it. The Capitol police, whatever twinges of sympathy or moments of soft demeanour they displayed, for the most part stayed firm.

Looting and ritual destruction

By ritual destruction I mean behavior that is seemingly purposeless, to outsiders and opponents. But it is meaningful, or at least deeply impulsive, for those who do it: a collective, social emotion for those involved.

Looting is generally of this sort. It rarely takes anything of value. In riots, including those that take place in electrical black-outs, the early looters tend to be professional thieves, but the crowds that come out to look and see broken-in store fronts are often caught with goods that they have no use for; they just join in the collective mood, a holiday from moral restraints when everything seems available for free. (This is also visible in photos taken during the looting phase of riots.)

In political protests and uprisings, looting does something else. Usually in the first phase of riot, especially a neighbourhood riot, after the first confrontation with the police, there is a lull while the police withdraw from the outnumbering crowd to regroup and bring reinforcements. In this lull, the emotional mood will drain away unless there is something for the crowd to do. Looting is a way to keep the riot going-- sometimes along with arson, even if it means burning your own neighbourhood; the smoke and flames in the sky carry a visual message of how serious the situation is. And looting is made possible, and easy, because police are visibly absent. Without opposition, the atmosphere is like a holiday; and at least temporarily it is a victory over the absent enemy. Looting is emotionally easy; there is no face-to-face confrontation. It provides a kind of pseudo-victory over the symbols of the enemy.

This was the situation in the Capitol after about 3 p.m. The attackers had been driven back from their political targets. Heavily equipped and menacing-looking tactical police squads are now pushing back the crowd, chiefly in the dense areas of the Capitol around the Rotunda. But it is a building with several wings and multiple floors, numerous stairs, a labyrinth of offices. This is the period when rioters spread out, penetrating far-flung corners where the last would not be dislodged until after 5 p.m. This is when the looting and ritual destruction mostly took place.

A prime target was House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office. Looters flipped over tables, ripped photos off the walls, damaged her name plate on the door. One of her laptops was stolen, as were those in other offices. The office of the Senate Parliamentarian was ransacked, as were other offices. Some places had graffiti: “Murder the media” was one of them, at Press rooms with damaged recording and broadcast equipment. These we can interpret as specific political targets.

Broken doors and cracked or smashed windows were throughout the building, leaving the floors littered with glass and debris. Some of this happened in the process of breaking into locked areas. But it continued in remote office spaces; presumably this was ritualistic destruction, just prolonging the attack-- precisely in places where guards were not present, while their main force was concentrated elsewhere.

Photos taken in the aftermath do not show a great deal of trash or destruction in the main corridors. Some of the furniture piled up was from improvised barricades by the defenders. Art works in the main galleries and display areas were not attacked-- presumably these had little meaning as enemy targets for the intruders. Some statues and portraits were covered with “corrosive gas agent residue”-- this would include tear gas and smoke bombs set off by the defenders, and (perhaps a small amount of) bear spray used by the attackers. In other words, this damage was an unintended by-product of the fighting that took place. Note too that these were “non-violent” weapons, designed to drive away opponents and avoiding lethal force.

If the looting and ritual destruction was intended to be a symbolic attack upon the Capitol, it succeeded in frightening and angering its officials. It was a ritualistic exercise on both sides-- which is to say, a war of emotions.

A far more destructive instance is the last comparison we will consider.

Paris, August 10, 1792

It was the day the French Revolution turned radical. Up till now it was a Constitutional Monarchy, the King ruling together with the Assembly. But tension had grown as the King vetoed punitive laws against nobles who fled the country and priests who refused to become civil servants. Tension grew worse as foreign troops threatened French territory to restore the old monarchy.

The royal palace had already been invaded 7 weeks before. On June 20, the third anniversary of the Tennis Court Oath in 1789, when reforming aristocrats had gone over to the National Assembly, a memorial demonstration of 10,000-to-20,000 surrounded the Tuileries. Carlyle summed up: “Immense procession, peaceable but dangerous, finds the Tuileries gates closed, and no access to his Majesty; squeezes, crushes, and is squeezed, crushed against the Tuileries gates and doors till they give way.” [p. xl] The King held them off, declaring his loyalty to the constitution, even wearing a popular “liberty cap” (the emotional force of a MAGA cap), and drinking a toast with them. Finally the Mayor of Paris arrived and persuaded the demonstrators to leave. In the aftermath, a wave of sympathy for the King split the Assembly. But efforts to swing back to moderation stalled, and news from the front raised further alarm as the enemy advanced. In Paris, everyone expected another assault on the palace, this time for keeps.

Security was beefed up. Courtiers in the palace went around armed and prepared barriers. The National Guard-- an official militia-- were urged to defend the crown against the sansculotte mob, but their loyalty was questionable, and a force of Swiss Guard was relied upon. On the other side, contingents of volunteers poured into Paris on their way to reinforce the front. The coming assault was an open secret. The “patriots... were now openly talking of storming the Tuileries as the Bastille had been stormed, and establishing a Republic.” [Doyle, Oxford History of the French Revolution, p. 187]

The organizational center of power was slipping away from the Assembly. The radical political clubs of Paris, the Jacobins and others, agitated in the neighbourhood sections to coordinate action in a revolutionary commune. Distrusting the National Guard drawn from the wealthier citizens, they called out the sansculottes (those without fashionable knee breeches) of small shopkeepers and artisans. In late July, panic over the invading Prussian and Austrian armies moved the Assembly to distribute arms to all citizens-- even though the arms could and would be used against themselves.

In the small hours of the night before August 10, the continuous ringing of the tocsin bell proclaimed emergency. The central committee of the Paris sections declared an insurrection and ordered all forces to march on the Tuileries. “Arriving there at nine the next morning, they found that the King and his family had fled to the safety of the Assembly across the road.” Defending the palace were about 2000 National Guards, but these immediately defected to the Commune’s side, a crowd of about 20,000. Courtiers had put up a brave show before the attack, but now withdrew. This left the 900 Swiss Guards, professional mercenaries, who began the action by opening fire. Their initial volley did not deter the huge crowd, and their allies melting away no doubt eroded their confidence. After about an hour, “the Swiss began to retreat, pursued by mobs of bystanders without firearms who hacked them to pieces with knives, pikes, and hatchets, and tore their uniforms to pieces to make trophies... crowds rampaged through Paris destroying all symbols and images of royalty down to the very word “king” in street names.” [Doyle, 189]

Carlyle summarized contemporary accounts in his own rhetoric of the 1830s: “Till two in the afternoon the massacring, the breaking and the burning has not ended... How deluges of frantic Sansculottism roared through all passages of the Tuileries, ruthless in vengeance; how the valets were butchered, hewn down... how in the cellars wine-bottles were broken, wine-butts staved in and drunk; and upwards to the very garrets, all windows tumbled out their precious royal furnitures: and with gold mirrors, velvet curtains, down of ripped feather-beds, and dead bodies of men, the Tuileries was like no garden of the earth... bodies of Swiss lie piled there; naked, unremoved until the second day. Patriotism has torn their red coats into snips; and marches with them at the pike’s point.” [Thomas Carlyle, The French Revolution, 1837/ 2002: 499]

Paris was now in the super-dangerous situation of rival centers of power, the Assembly and the Commune. Both of them commanding armed forces; both internally split among mutually distrustful factions, fearful of what their rivals would do, and motivated to strike first out of fear of what would happen if they didn’t. But the initiative had passed to the Commune, and its radical political clubs; they had won the big victory, and demonstrated the awesome force of the mobilized crowds of Paris. Awesome because of its emotional pressure, its all-encompassing noise, its sheer size, and its ferociousness, now several times demonstrated, when opponents wavered and it had them at their mercy. Guillotines were being set up. In future months, the King and Queen would be executed, along with thousands of others, aristocrats, priests, and just plain political rivals, anyone who aroused suspicion of whatever faction was temporarily dominant. This would go on for two years, until Robespierre was executed and a reaction began to swing back towards unitary authority and eventually dictatorship.

During these two years there was a veritable mania of renaming. Forms of address, Monsieur and Madame, were forbidden; everyone was to be called Citizen. Churches were declared temples of Reason. The old Christian calendar was abolished, its A.D. (anno domini) and B.C. (before Christ) replaced by Year One, starting with the declaration of the Republic in September 1792 (oops, old-style!) While we’re at it, all the names of the months have to go too, for instance the month of July is now called Thermidor. Symbolic politics glorifies the hopes and projects of the most radical intellectuals. These changes would remain in place until Napoleon brought back the church and reinstated the old calendar in 1801.

Lessons learned?

What was unusual about the Capitol assault of January 6, 2021 was how quickly and easily it was defeated. Yes, it had factional splits and dispersed centers of command, wavering and dissenting about sending reinforcements; it had police retreating before an aggressive crowd; reluctance to shoot; some fraternization between attackers and guards; some ritualistic looting at the end. It had a background of long-standing and accumulating tension between two sides, counter-escalating social movements, politicians jumping on and off of bandwagons. But in historical comparison, it had no overwhelming consensus that the regime was toppling, much less that it ought to topple. The assault was defeated, in a momentum swing of about an hour, and with an historical minimum of serious casualties. That it could be put down so easily is a testiment to American institutions. A federal democracy, with powers shared and divided at many levels among executives, legislatures, and courts, there is no place to turn the switch that controls everything. Decentralized democracies like the USA can have civil wars-- if geographical splits are severe enough and include the armed forces; but it cannot have coups at the top or revolutions in the Capitol.

REFERENCES

Leon Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution. 1930.

John Reed, Ten Days that Shook the World. 1919.

Thomas Carlyle, The French Revolution. 1837.

William Doyle, Oxford History of the French Revolution. 2002.

Alexis de Tocqueville, Recollections: The French Revolution of 1848. 1850.

Randall Collins, Violence: A Micro-sociological Theory.2008. [data sources on forward panic; firing and non-firing in violent confrontations; layers of participants in riots; looting]

Charles Tilly, The Politics of Collective Violence. 2003.

Anne Nassauer, Situational Breakdowns: Understanding Protest Violence and Other Surprising Outcomes. 2019.

Neil Ketchley, “The Army and the People are One Hand! Fraternisation and the 25th January Egyptian Revolution.” Comparative Studies in Society and History. 2014.

Randall Collins, Civil War Two. 2019. [thought experiment of what a replay of the Civil War of 1861-65 would be like with modern weapons]