The defeat of Hillary Clinton raises the question whether women are leaders in the same way as men. This is not a rhetorical question.

As a sociological theorist, I am inclined to think that men and women operate according to the same social processes. To put it another way: the dynamics of power in politics, social movements, and organizations operate the same way no matter who is in them. The process shapes the person.

Men and women have been different, historically, when and because they lived in different social spheres. Changing forms of state, family, and economy had drastically different ways of using men and women and shaping their possibilities.

But this is just a framework, not a proof. The question of when women are leaders-- and more specifically, charismatic leaders-- is an empirical one.

Four kinds of charisma

Start with a list of ostensibly charismatic leaders who were women. Ostensibly, because historical reputations are not always what they seem.

There are four main ways of becoming a charismatic leader.

[1] Frontstage charisma: moving large numbers of people into action as enthusiastic followers. Sometimes this is done by impressive speech-making (especially in modern times); sometimes by leading from the front (especially in pre-modern times). Dramatic public appearances may also generate the impression of charisma, although we need to sort out whether it is just a spectacle without real power to move people into action.

[2] Backstage charisma: gaining enthusiastic compliance in private, face-to-face encounters. This is the power of emotional domination on the personal level.

[3] Success-magic charisma: being perceived as unbeatable, running off a string of successes even against improbable odds. This kind of charisma is volatile and can vanish when it apparently no longer works. But even the greatest of success-magic leaders (Jesus, Julius Caesar, Alexander, Napoleon) came to bad ends, without losing their charisma. Unbroken success doesn’t exist, but how charismatic leaders manage the gaps is distinctive.

[4] Reputational charisma: being known as charismatic (in any of the above senses) amplifies one’s emotional appeal via a feedback loop. But keep in mind the main criterion: leading enthusiastic followers into action. Merely attracting attention or audience appeal is not the same as power; celebrities and figureheads are trapped by their onlookers more than they lead them. And there is a tendency for any famous names from the distant past to be regarded as charismatic; it requires investigating whether they actually had any of the first three types of charisma. Charisma is not the only mode of leadership.

Charismatic leaders were skilled at one or more social processes 1-2-3. By examining micro-details of how they interacted with people in different kinds of situations, we can assess how strong or weak they were in different areas. Jesus Christ and Julius Caesar were superlatively good at all three-- frontstage, backstage, and success-magic charisma. Steve Jobs was emotionally dominant in backstage encounters, learned to make enthusiasm-generating public appearances, and had a run of success-magic interrupted by a lengthy down period. Alexander was good at 1 and 3 but not 2.

Among the women we will examine, Joan of Arc displayed all three charismas in her brief career. She too came to a bad end, but struggles for power are contentious, and a charismatic leader for one side is not charismatic for the opposition.

We will also look at Cleopatra, probably the most famous woman leader in history. (The Blessed Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus, may be even more widely known; but her fame is derivative, and she was not in any way a charismatic leader.) Just what Cleopatra’s charismatic skills were must be shown, leaving open the possibility that she may be only a case of reputational pseudo-charisma.

Finally, I will consider Jiang Qing, wife of Mao Zedong, and the principal instigator and leader of the Cultural Revolution. Nominating women as charismatic leaders from the present or very recent past has the disadvantage that partisan opinion varies greatly about them. I am hesitant to suggest any women political leaders now living just because they have fervent admirers. Considering Jiang Qing, condemned and vilified as leader of the Gang of Four, has the advantage that we can examine a genuinely mass movement that she set in motion. And as we shall see, she combines some aspects of Cleopatra and Joan of Arc. Is it because of the peculiar circumstances of power in Mao’s China that a charismatic woman leader appears there, more characteristic of pre-modern societies than of modern ones?

As far as pathways to charismatic power, modern democracy may be a game-changer, especially for women, and not in the direction you might expect. Hence the value of looking at charismatic pre-modern women, and such throw-backs that still exist outside of modern democracies.

Joan of Arc

Jeanne d’Arc (ca.1411 to 1431) had all the forms of charisma to an intense degree.

Frontstage charisma: She was not a great public speaker. In an age of dynastic politics, without democratic assemblies, there were few speeches except sermons of itinerant monks. But she moved people, emotionally and physically.

In battle, she led from the front. Although she wore armor and carried a sword, personal violence was not how she led the battle line. She carried a banner with the royal fleur-de-lys of France and the soldiers would charge behind her. This was an era when commanders could line up their troops for battle, but once it started, there was virtually no way they could send orders. What kept troops in formation-- if at all-- was to rally behind their banners. Joan’s military style was to attack; with herself in the front, she was exposed to the utmost danger. Her soldiers had to swarm closely behind her to protect her; otherwise she would be killed or captured. And swarm they did. As the great military historian John Keegan has shown (first when analyzing the battle of Agincourt, which happened when Joan was about 4 years old), troops did not win or lose a battle because of the physical shock when two battle lines clashed; it was a psychological shock, that made defenders waver and pull back. Running away was dangerous: that was how most soldiers were killed, in a posture unable to defend themselves and without the solidarity of their own line to fend off the enemy. Joan provided the emotional domination that broke the enemy line. It was quite literally charismatically led victory.

Her crowd charisma was building up for several months before she commanded the King’s forces. As she traveled from her home to the royal court, and then to the siege of Orleans for her first battle, she was greeted by crowds all the way. Her word of mouth among the common people was terrific; and this eventually was transmitted to the soldiers. Once launched, she traveled everywhere in a mass spectacle.

How did this get started? She acquired the reputation of a woman who heard voices from the highest saints, conveying the will of God, with a political message: defeat the English and crown the Dauphin as King of France. At key points-- talking with aristocrats and officials-- she told them what the voices said. But this was not so much a solo as an aria against the background of a rising chorus, the adulation of her admirers. Joan went to church as often as possible. When traveling, even on an urgent mission, she would stop at churches en route to hear mass. One gets the impression these were not regularly scheduled masses such as exist in Catholic churches today; but that the local priest would say a mass for Joan and her followers.* Joan was always extremely moved, and wept copiously. The audience was not only impressed by her sincerity, but joined in weeping. At the beginning of her charismatic career, it is no exaggeration to say that she led people in contagious weeping.

*This was not unusual at the time. At Agincourt, the English King Henry V heard mass three times in a row while waiting for battle to begin.

We moderns find it hard to get our heads around this; for us weeping is sadness, or at best a private breakdown of being overwhelmed by personal feelings. But the history of emotions has drastically shifted. Throughout the Christian Middle Ages, the climax of public encounters was often weeping: monks would weep as they pled for someone’s salvation or recovery; feuding families would reconcile by throwing themselves at each other’s knees and weeping; defeated burghers would meet their conquerors by kissing their hands and asking for mercy, which was accepted when the conquerors too joined in the weeping. Collective weeping was the main form of high-emotional solidarity, above all newly created solidarity as divisions and conflicts were (temporarily) overcome. Joan’s procession across France was a series of weeping-fests. It happened not only in church. Wherever she stayed, people of all ranks would come to see her; they might arrive as skeptics or political adversaries, but would come away convinced by her genuineness. It was not so much that she told them about her visions, but that they were impressed by her humility and simplicity. She was everything that a saint should be. She brought tears to their eyes.

We have another problem of anachronism. Joan was doing all this when she was 17 or 18 years old, in an era when women were subordinate to men. In our bureaucratic society when no one is allowed to do anything important until they are officially adults and generally quite a lot longer working up through the ranks, this seems impossibly young. But Charles VII, the Dauphin, succeeded his father when he was 19; English Kings like Henry V and Henry VIII were leading troops and actively reigning as early as age 14-to-18. Joan had no hereditary right to anything, but the fact that she was young and female just added to her marvelousness. She called herself Jeanne la Pucelle, Joan the Maid or Virgin. It helped there was cultural resonance with the cult of the Virgin Mary, at its height during those centuries.

Backstage charisma: Joan’s personal impressiveness had been building up since at least her early teens. She was the youngest of five children, daughter of a prosperous farmer who was headman of little village amid the battlefields of northeastern France. Her father was a man of some importance, who contracted business with local nobles and lawyers. He took over an abandoned castle to serve as a refuge against the raids of mercenary soldiers-- and where Joan might imagine herself a Queen. Joan sometimes joined her siblings in farm work but her mother indulged her indoors; they lived next to the village church, where Joan attended assiduously. She was extremely sensitive to what was going on around her, and had an early desire to be a soldier-- so much so that her father threatened to drown her in the river if she went off with soldiers (marauders in bad repute). George Bernard Shaw was at pains to argue that she was no beautiful romantic heroine but plain and asexual; she was tall and strong, with all the seriousness of the managerial women that Shaw was extolling in the early 20th century women’s movement. (I imagine her as a star soccer goalie.) Having miraculous visions was not unusual among the medieval folk; there were shephard boys exhibiting bleeding stigmata, beggars who started crusades and children who went on them. Joan stood out from her competitors in the miracle field by adding the image of a woman warrior, and bringing a message combining religion and politics at just the moment when France was in its deepest crisis.

It is revealing who her three inspirational saints were: St. Michael, actually archangel, the one with the fiery sword who expelled Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, and the chief of God’s forces in combating the Devil. St. Catherine, an ancient martyr of royal Egyptian descent (the lineage of Cleopatra!) who endured tortures to proclaim Christianity against the Roman Emperor. St. Margaret, a refugee from the Norman conquest of England, who fled to Scotland and married the Scottish King. It is a collection of supernatural military power, exemplary fortitude in martyrdom, and religious Queens-- and anti-English to boot. Joan called them her “Council” as if they were her official advisors. As Shaw pointed out, Joan was the type of person who thinks in visual images; the voices she heard in her head, her internal dialogue, was always politically up-to-date.

Joan’s practical task was to convince supporters who would convey her to the royal court, then in exile from Paris, which was held by the English. She had heard voices for about 5 years before she launched her program; i.e. by the time she was full-grown, but also the moment when it appeared the French dynasty would be extirpated by crowning the English King Henry VI -- then a child of 8-- as King of France.

Her father would not support her initially (Jesus had the same problem of not being a prophet in his own home town), but she convinced her uncle to introduce her to the local military commander. She convinced him by what seemed to him a miracle: she told him of the defeat of French troops trying to raise the siege of Orleans (Feb. 12, 1429) before the commander himself had heard of it. When the news arrived, this seemed like a miraculous prediction. It is characteristic of charismatic persons to be perspicacious. Joan’s village was on the main east-west route from Paris into Germany, and on the north-south road along the Meuse River connecting Flanders with Lorraine and Burgundy, a cross-roads flowing with refugees and soldiers; it was not unusual for a peasant to be more aware of approaching dangers than a ranking nobleman.

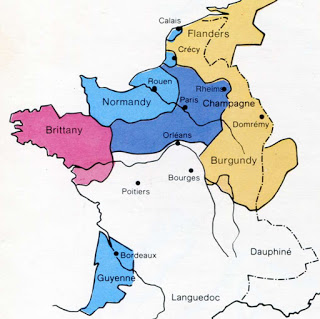

And Domrémy, her village, belonged to the personal domain of the Kings of France-- as distinguished from lands held by feudal lords in the unsteady chain beneath the King. Her location made her a French royalist, at a time when the Duke of Burgundy was far richer and the expanding power, although potentially stymied by the dangerous game he was playing with the English and other feudal contenders. The local commander was convinced enough to give her armour, a horse, and a small military escort, plus an introduction to the Duke of Lorraine-- a relative of the Dauphin’s Queen. So she was launched, picking up reputation along the way, manifesting religious charisma with her combination of national crusade and contagious weeping.*

* It is convenient to think of Paris as the center of a clock, with an hour-hand about 125-150 miles long; Domrémy is at 3 o’clock; the Dauphin’s court at Chinon, 4.30;

Poitiers, where she was examined by a parlement, 7.30; Orleans, where she raised the siege, 6.30; Rheims, the ancient cathedral city where she took the Dauphin to be crowned, back up at 1.30; the remainder of her career spent fighting outside of Paris and where she was captured, 1.00; burned at the stake at Rouen at 11 o’clock in English territory near the Channel. The battle of Agincourt happened further north, at 12 o’clock.

Arriving at the Dauphin’s court at Chinon, Joan entered a political situation of rival factions. Famously, the Dauphin hid himself among the courtiers; but she picked him out immediately despite lack of royal insignia. We are in the realm of miracle stories, or what passed for them; but a person with acute observation, who had no doubt heard gossip of the Dauphin’s immature personality, would have little difficulty in scanning body postures and facial expressions to find the pocket of uneasiness in the crowd where he was pretending. Another incident from the same period is more telling. One of the soldiers swore loudly and made a lewd comment about her. She approached him and said: “A pity that you blaspheme against God, when you are about to die.” Some time thereafter (probably not the same day) the man fell into a river or moat wearing his armour and drowned. Whether accurate or not, it solidified her miraculous reputation. It illustrates her ability (again like Jesus) to pick people out of crowds and confront them individually, shifting the tone to something jarring and unexpected. It is not at all impossible that he was unnerved by the prediction of his imminent death, reinforced by the following that Joan already had, even in the divided court and certainly among the common people. In effect, she gave him the evil eye, like the bone-pointing magic dreaded in primitive tribes.

And so throughout the up-phase of her career. The court politicians being divided, they referred her to a parlement (a conclave of canon lawyers, not a legislative assembly) at Poitiers. The churchmen quizzed her skeptically about her voices and visions-- contrary to modern views, the Catholic church was not a push-over for miracles, and aimed to cull out the many contenders. One learned theologian asked her what language her voices spoke; “Better than yours,” she replied to his provincial accent. Asked to produce a miraculous sign of her authenticity: “My sign will be to raise the siege of Orleans,” she responded. “Give me the soldiers and I will go.” Full of self-confidence, she was not intimidated by authorities. They quoted theology to her. “There is more written in God’s book than in all of yours,” she said. Unabashed-- this was a time when most women, even aristocrats, were illiterate-- she called for paper and ink and dictated a message to the English commanders: “I order you in the name of the Heavenly King to return to England.” Again, the calm confident tone: not angry nor argumentative, but taking the initiative as a matter of course. The judges wrote her message. *

* How did Joan learn to argue with professionals? A clue is that her parents tried to dissuade her from her mission by getting her married. A young man brought a suit that she had been promised to him. She argued the suit herself before an ecclesiastical judge and won. In her early life, most of the time she was silent about her voices; she was learning when to speak and how.

Given a command of soldiers, she quickly changed the tone of the army. Troops were a mixture of nobles with changeable loyalties, upstarts and mercenaries making their way in a time of political chaos; and in any local battle, crowds of peasants who might be attracted to scavenging and revenge on the wounded and dead. Joan gave religious fervour to the peasants, the initial support of her charisma. From the professional soldiers, she demanded that they cease cursing, and to put away the camp-followers who entertained soldiers with sex and drink in the long periods between battles. Shaw remarks on the power of prudery in restoring order and morale in the army-- in this case, one that had gone through a disastrous series of defeats. Probably not prudery per se, but Joan’s focus on purpose and self-control; she converted some of the troops and got the most fervent to follow her in assaults previous commanders were unwilling to attempt. As mentioned, she led more with her banner than her sword; the only instance recorded of her using it was when she used the flat of her sword to drive away prostitutes from the camp -- rather like Jesus driving the money-changers from the temple. And she turned mercenary soldiers, who got most of their income from looting and by taking prisoners for ransom, into fighters for a national cause.

Success-magic charisma: Her first success was to be heard.

As she proceded from her family circle to the local commander-- to the Duke of Lorraine-- to the Dauphin’s court-- to the Poitiers parlement-- her supporters grew and stories of her successes in winning over the elites were esteemed as miracles. In two months, she had electrified the populace in a swath across central France. Reaching Orleans at the beginning of May, she entered the city in a paroxysm of public enthusiasm. She rode around the walls followed by the city population, even closely inspecting the silent English fortifications. At vespers in the cathedral, she wept and brought everyone to tears. When French troops arrived, she paraded them back and forth before the English, as if the sheer manifestation of support would drive them away.

The English siege hinged on blocking supplies and reinforcements, while the besiegers themselves occupied a string of forts outside the walls. Rival bodies of French troops squabbled over accepting Joan’s leadership and held back from attacking these bastilles.

Finally they launched an attack without telling Joan; the attack failed but Joan turned around the retreating soldiers and with her crowd of followers, took the first bastille. Joan devoted the next day to prayer, while the English consolidated their scattered forces, and the French plotted to attack again without Joan. Orders were left to keep the city gates closed upon her; but the clamor of her followers overawed the commander of the gates.

When she arrived at the strongest bastille, the attack was flagging; she jumped into the moat and was holding a ladder against the wall, ignoring a shower of arrows when one pierced her through the shoulder. Carried to safety, she insisted on staying nearby. Handing her banner to a trusted follower, she told him: “As soon as the standard touches the wall, you will be able to enter.”

“It is touching now.”

“Then go in, the position is yours.” The attackers went up “as though there had been stairs.”

A crowd of civilians surged behind them; bridges collapsed under cannon fire; English resistance disintegrated inside the bastille and the defenders were all massacred.

The six-month siege was lifted; the remaining English retreated and were beaten again on the road, this time without Joan’s leadership. It had been the high-water mark of English penetration, the last major French city not in English hands.

1422

blue: English;

yellow: Duke of Burgundy;

purple: Anglo-Burgundian;

pink: Duke of Brittany;

white: France

French war-lords now wanted to follow up by liberating their own corners of France, but Joan focused on the political goal: to get the Dauphin crowned. This meant escorting him through hostile territory to Rheims. On the way her army was challenged by a garrison from the fortified city of Troyes. Bringing her banner before the city walls, she was followed by a crowd of common people who rapidly filled the moat with firewood and trash, creating a bridge for the soldiers to cross. The citizens panicked and the occupying troops parlayed to evacuate the place-- a nearly bloodless victory. In a little more than two weeks, she brought the Dauphin to Rheims and had him crowned. She had won the race. She knew the English King could be proclaimed in Paris (and indeed he was, in 1431) but Rheims was the traditional coronation place, and she got Charles there first. In the cathedral she clasped the King’s knees and burst into tears, joined by the entire congregation.

There was a good deal more of France to be reconquered, but the momentum had shifted. Joan’s successes had reversed a string of disastrous defeats: Agincourt in 1415, major losses again in 1421, near-annihilation of the French army in 1424, a bad defeat on the road to Orleans a few weeks before Joan started out in February 1429. After the coronation, Joan wanted to take all possible forces and recapture Paris, but the war-lords had other priorities. King Charles VII took the occasion to make a triumphal procession through the north-eastern territories, receiving the capitulation of cities that had sided formerly with the English.

Meanwhile, a fresh English army arrived to reinforce Paris. When Joan attacked the outer moats in September, she was wounded by an arrow through her thigh while plumbing the depth of the water with her spear and calling for the moat to be filled. Without emotional momentum, the place could not be carried and the French took 1500 casualties. Her victory string was broken; enthusiasm on her side was turning to blame. Joan was reduced to one among other commanders. In minor battles outside of Paris, she took one city, but at another the siege dragged on until the attackers themselves dispersed in an episode of rumour and panic. Joan was still bold but her crowd magic no longer worked. Within a year, in May 1430, she was captured while trying to relieve a Burgundian siege of Compiègne. As soon as she arrived, she led a sortie that almost succeeded, but a counter-attack drove them back. Joan, covering the retreat, was isolated on the wrong side of the moat, surrounded and pulled from her horse.

Sold to the English under the ransom system, she was tried as a witch (the enemy interpretation of her supernatural voices) and executed. None of her former allies tried to rescue her. The King himself no longer needed her. She had rescued him from being treated like a child by his courtiers; but she treated him like a subordinate too, under the voice of God. In fact, Charles VII had grown up and became quite a capable King, reigning for 30 years and overseeing the rebuilding of the French state. Becoming a martyr like St. Catherine must have been in the back of Joan’s mind, if not in her game plan. Her voices failed her, for the first time, by assuring her she would be rescued. When she realized the voices were wrong, she stopped trying to escape (she had jumped from a 60-foot tower and survived), and gave in to her fate. Both the inner and outer sources of her charisma, her voices and her crowds, were gone. Her effective charisma had lasted a little more than a year, most intensely in the first few months.

Reputational charisma: The downstream of history was good to Joan’s reputation. She was burned in 1431 after a lengthy show trial designed to bolster English legitimacy. But the tide had turned: the English gradually lost their gains in the north, accelerating after 1435 when the Duke of Burgundy switched sides and made a treaty with the French King. In 1436 Charles VII was able to enter Paris on his own. By 1453, the English lost their southwest territories in France, a long hold-over from Norman days of patch-work feudalism, and the Hundred Years’ War was over. It was just at this time that the verdict of Joan’s witchcraft trial was reversed by French jurists. After 1455 England was busy with its own civil War of the Roses and unable to intervene abroad.

Joan had not only saved the crown lineage but made a step towards reforming the army. At the time of Agincourt, it was no longer feudal service by retainers who followed their lords in return for grants of land; soldiers were promised pay but seldom received it, and they lived off the people and the war itself by looting and ransom. One reason troops were so unwilling to risk combat was they were only attracted when chances were good for taking lucrative prisoners. The English archers who had slaughtered the French knights at Agincourt were outside the system-- too poor to be worth ransoming; neither were the peasant crowds who aided Joan. The most cynical kind of warfare was being displaced by a more ideological kind. Charles VII followed up in the late 1430s and 40s by decreeing a royal monopoly on raising troops, at the same time prohibiting anyone but the crown from imposing taxes. The reforms met resistance but eventually enough royal companies were raised (paid and equipped by local communities) to expel the English. It was the end of feudalism and the beginning of the modern state; although it took Charles VII’s son, Louis XI (r. 1461-83) to establish more or less the borders of modern France. Lous XI was hardly a hero; his successes came by diplomatic marriages and negotiations, together with grasping for revenue wherever he could. Crooked and spider-like, paranoid over plots and assassinations (he himself had rebelled against his father), Louis XI built France as we know it, but could hardly be adulated for it. All the more opening for the reputation of Joan of Arc, the woman who saved France.

Cleopatra: sexual power in dynastic politics

Cleopatra VII, Queen of Egypt, lived from 69 to 30 BC and reigned from 51 to 30. The dates tell us something: Not only did she come to power when she was 18 years old, but she was 39 when she died by suicide. That means she was an effective politician at a time when her throne was constantly under threat, holding on for 21 years. Although she is legendarily sexy-- the most famous example of sexual power in all history-- that doesn’t explain much, considering that extremely beautiful and erotic woman have generally been prized objects rather than independent actors.* One could make out a case that powerful women have generally been plain-looking.

* A very beautiful woman of my acquaintance, who has had a career as a political insider, replied to my question about whether being beautiful was an advantage: It’s a disadvantage-- men don’t take you seriously.

In fact, how beautiful was Cleopatra? There are several surviving likenesses. One version shows a woman, no longer young, without any of the trade-mark features like huge coloured eyeliner, and not especially attractive. The other shows her in a stereotyped pose as as Egyptian goddess.

Contemporary busts of Cleopatra VII

Cleopatra VII as temple goddess

Modern image of Cleopatra

No question, she was a political operator of great skill. She was dealt a weak hand and played it far longer than might be expected. She took on three of the most famous men in antiquity, Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, and Octavian/Augustus Caesar and played them, on the whole, to a draw or better. Was she a charismatic leader? Let us examine the criteria.

Frontstage charisma: Cleopatra did not make speeches, but she certainly knew how to attract crowds. She visited Julius Caesar in Rome in 46 BC, 2 years after their affair in Egypt. We don’t know if she resembled Elizabeth Taylor hauled on a huge golden replica of the sphinx, but she made quite a stir. She brought along their son Caesarion (“little Caesar”), and her official husband, her younger brother Ptolemy XIV, plus a large following. Caesar put her up in his country house and had a gold statue of Isis, resembling Cleopatra, erected in his family temple in the Forum. All this scandalized the Romans, especially the conservative republicans, all the more so since Caesar’s own wife was in Rome, and Cleopatra was lobbying to have Caesarion named his heir. Cleopatra’s presence could well have encouraged the rumour that Caesar was planning on making himself King, and thus his assassination. (Talk about femme fatale.) In fact she was still in Rome on the Ides of March 44 BC, and left for Egypt soon after.

She had already shown her boldness at home. Cleopatra was Greek, of the dynasty that had ruled Egypt since 300 BC. Although her ancestors always spoke Greek, Cleopatra was the first to rule her subjects by speaking Egyptian; in fact she could speak 9 languages and negotiated personally with neighbouring powers. She further solidified her power at home by having herself declared a reincarnation of the goddess Isis, and made herself the first female Pharoah.

An even more spectacular incident was in 41 BC during the civil wars. Mark Antony summoned her to Tarsus (southern Turkey) on charges of having supported his rival. As Plutarch describes it:

“She sailed up the river Cydnus in a barge with gilded poop, its sails spread purple, its rowers urging it on with silver oars to the sound of the flute blended with pipes and lutes. She herself reclined beneath a canopy spangled with gold, adorned like Venus in a painting, while boys like Cupids in paintings stood on either side and fanned her. Likewise the fairest of her serving maidens, attired like river sprites and Graces, were stationed, some at the rudder-sweeps, and others at the reefing-ropes. Wondrous odours from countless incense-offerings diffused themselves along the river banks.”

Even more important was the crowd reaction:

“Of the inhabitants, some accompanied her on either bank of the river from its very mouth, while others went down from the city to behold the sight. The throng at the market-place in Tarsus gradually streamed away, until at last Antony himself, seated on his tribunal, was left alone.”

Antony is dominated before he even sees her. He invites Cleopatra to dinner, but she makes him come to her. Of course! on her own turf:

“Antony obeyed and went. He found there a preparation that beggared description, but was most amazed at the multitude of lights. For, as we are told, so many of these were let down and displayed on all sides at once, and they were arranged and ordered with so many inclinations and adjustments to each other in the form of rectangles and circles, that few sights were so beautiful or so worthy to be seen.” (For its day, long before electricity, Lady Gaga’s light show in the Superbowl.)

Cleopatra was surrounded by lavish spectacle, but far from being trapped by it, like Queen Elizabeth in her fancy gowns amid her courtiers, or most Chinese and Japanese Emperors. Antony intended to shake down Cleopatra for money for his campaign against Parthia (the big threat just then expanding from Iran into Syria); he ended up following her to Alexandria for a year and neglecting his wars. Cleopatra knew how to trap others in her spectacles, adjusting them to the victim’s personality. Plutarch comments that Cleopatra observed Antony liked jests and pranks, and adopted the same manner towards him.

“She played dice with him, drank with him, hunted with him, and when by night he would stand at the doors or windows of the common folk and scoff at those within, she would go with him on his round of mad follies, wearing the garb of a serving maiden. Antony also would array himself as a servant. Therefore he always reaped a harvest of abuse, and often of blows, before coming back home; though most people suspected who he was. The Alexandrians liked him, and said that he used the tragic mask with the Romans, but the comic mask with them.”

Antony was quite literally being a playboy, and Cleopatra was egging him on. They created an exclusive club, dedicated to outdoing the other in the profusion of their expenditures. Plutarch’s grandfather, who was a physician in Alexandria at the time, said the royal cooks prepared food for a huge banquet, even though it was an intimate dinner, but cooked at different speeds, so that whenever Antony had a whim for a particular dish, it would be ready immediately.

They would give away all the gold beakers on the table for a clever remark. Cleopatra reportedly bet him she could spend a fabulous sum on one dinner; when it arrived, it was quite plain, but then she called for a chalice of wine, dropped her best pearl into it, and drank it.

Nevertheless, there was method in the madness, or culture in the context. It was a period when Roman generals used wars and foreign conquests as income-making machines, both to pay their soldiers, and to win votes with the populace in Rome. Julius Caesar, although no party-animal himself, was famous for the extravagant games and gladitorial shows he would put on before an election. Cleopatra knew what she was doing. Egypt had the reputation of being the wealthiest part of the ancient world, and she was constantly impressing Antony with this, no doubt instilling the idea it would be better to be ruler of the world from Egypt than from Rome. And extravagant splendour was a public statement. Especially in the East, it was customary to bring mythology to life, in more than half-serious fashion. When they first met at Tarsus, Plutarch says: “A rumour spread on every hand that Venus was come to revel with Bacchus for the good of Asia.” *

* After years of playing Bacchus in Alexandria, Antony’s story was about to end in 30 BC by being crushed by Octavian’s army. Plutarch reports the rumour that went around the city: “During the middle of the night, when the city was quiet and depressed through fear and expectation of what was coming, suddenly harmonious sounds from all sorts of musical instruments were heard, and the shouting of a throng, accompanied by cries of Bacchis revelry and satyric leapings, as if a troop of revellers, making a great tumult, were going forth from the city; and their course seemed to be toward the outer gate which faced the enemy, where the tumult became loudest and then dashed out. Those who sought the meaning of the sign were of the opinion that the god to whom Antony was always most likened was now deserting him.”

Cleopatra played the frontstage charisma of spectacle in her own key. Her leadership style in other areas had ambiguous results. Except when Caesar or Antony were present, she played the man’s role. Her most important geopolitical weapon was the Egyptian fleet. It had been traditionally the strongest in the Mediterranean. Its strength kept the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt the most durable of the three successor states that divided up Alexander’s empire. During the wars of the Hellenistic period, there had been an arms race in naval power; the banks of oars that gave ships speed and power to ram the enemy had gone from triremes (three decks of rowers) to enormous battleships with six banks of oars. By Cleopatra’s time, the Romans were catching up, but the Egyptian navy still had a big reputation-- something of a paper tiger, but it was Antony’s civil war that would find that out. In the same way, Alexandria towered over Rome in its monumental architecture (Octavian would fix that when he became Augustus). Cleopatra’s task was to keep up appearances.

She commanded the fleet herself on at least two important occasions. In 43 BC, as the Antony/Octavian alliance was still battling it out with Brutus’ faction, Cleopatra took her fleet out into the Mediterranean in an effort to bring supplies to Caesar’s successors. The fleet was badly damaged by a storm, Cleopatra was sick, and they returned to Egypt. A more famous failure was in 31 BC, at the battle of Actium (on the Aegean coast of Turkey), where Antony’s and Octavian’s fleets lined up for a showdown. Cleopatra again personally commanded the Egyptian fleet, which was in reserve at the rear of Antony’s ships. As the battle mounted, a wind came up-- filling their sails and making rowing unnecessary for speed; and Cleopatra suddenly took off with her fleet. Antony impulsively followed her in a single ship, and was taken on board. His fleet remained to fight, unaware their commander had gone; eventually as the battle subsided, most of Antony’s ships were captured, and when news of his desertion was confirmed, went over to Octavian’s side. Antony himself quickly regretted his impulse; for 3 days he sulked on the prow of Cleopatra’s ship, angry or ashamed to see her, Plutarch says; until Cleopatra’s women prevailed on them to reconcile and to eat and sleep together.

Clearly Cleopatra was no charismatic battle-leader. The reason for her flight has never been explained; the surviving accounts are all from the Roman point of view. Her strength was manipulating men, and here it proved too strong for her own good.

Backstage charisma: Back-track to 48 BC. Julius Caesar arrives in Egypt, chasing Pompey, the other famous Roman general, whom he has defeated in the first round of civil wars. Cleopatra is 21, exiled by supporters of her 13-year-old brother and co-ruler. Pompey had shown up seeking asylum, but Ptolemy XIII decided to curry favor with Caesar by having him executed and sending his head as a present. Julius, however, is offended-- possibly by a foreigner executing a Roman; possibly because this offered a good excuse to annex Egypt, much the same way that he had annexed Gaul. At this moment,

Cleopatra has herself smuggled into Caesar’s presence, rolled up in a rug. Exactly what happened is not known, but the result is a tremendous diplomatic reversal of fortune. Instead of annexing Egypt, Caesar puts Cleopatra back on the throne. Ptolemy XIII is killed in battle, and Cleopatra formally marries yet another brother, Ptolemy XIV. Julius, who is usually fast-moving and had plenty of mopping up to do in the aftermath of the civil war, stays some months in Egypt with Cleopatra, who has a son 9 months later.

How does she do it? Both Plutarch and Cassius Dio comment on her voice and her conversation. “For her beauty, as we are told, was in itself not altogether incomparable, nor such as to strike those who saw her, but converse with her had an irresistible charm... There was sweetness in the tones of her voice; and her tongue, like an instrument of many strings, she could readily turn to whatever language she pleased.” (Plutarch) *

* Shakespeare catches some of this, in Antony and Cleopatra:

Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale

Her infinite variety. Other women cloy

The appetite they feed, but she makes hungry

Where most she satisfies.

But Shakespeare depicts her as flighty and moody, and misses Cleopatra’s political astuteness and ruthlessness. George Bernard Shaw, who liked surprising reversals and usually took issue with Shakespeare, presents her in Caesar and Cleopatra as a frightened child. Incidentally, Shakespeare invents Antony’s famous “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears!” funeral address in Julius Caesar; it is the turning point of the play, but not mentioned in Plutarch. When Julius Caesar himself writes about his wars, he mentions Antony as someone who is good at delivering logistics and recruiting troops, and who can be relied upon to reinforce him at crucial moments. When Cleopatra first meets Antony, that is what he is doing: raising money from conquered cities. On the whole, Plutarch seems closest to the truth, except that he cannot see the politics from Cleopatra’s point of view.

Cleopatra’s emotional domination over others was a combination of sex and political awareness. She had a blithely pragmatic attitude about sex; she was married or shacked up four times (including twice to her brothers). This was an era of dynastic marriage politics; particularly in elite Roman families during the social wars and other feuds of the last century of the Republic, leaders would marry off their daughters or sisters in order to make an alliance; and divorce when alliances were broken. Julius, Pompey, Octavian, and Antony alike did this with each other. Love had nothing to do with it. Cleopatra was different in that she chose her own partners; and her most important liasons were for love. (Marrying her brothers was a matter of Egyptian royal custom, and she got rid of them as soon as possible.)

Cleopatra’s initiation into the great world had less to do with sex than with politics. Royal family politics in Egypt may have been closely-held, but it was anything but harmonious. Her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes, was overthrown in 58 BC in a coup that made his two eldest daughters co-rulers. Auletes went into exile in Rome, taking Cleopatra with him, until Roman military support put Auletes back on the throne in 55 BC. One of the daughters being already dead (probably murdered), Aultes had the other usurping daughted killed, and named Cleopatra and her next younger brother co-regents with himself. From age 11 she had an inside view of Roman politics while Caesar was conquering Gaul and forming the first triumvirate including Pompey. By 14 she was co-ruler of Egypt with her father; by 18 when her father died, ruler with her ten-year-old brother, whom she soon stopped mentioning in royal documents and depicting on coins. By 21, she had been pushed out in a coup, avoided assassination, and hooked up with Caesar (could they have talked Roman politics while having sex?)

Her rule in Egypt was never threatened domestically again. Her 18-year run itself was some kind of record, set against innumerable political murders of the previous half-century. Among her immediate ancestors, there were a dozen changes of ruler, only two of whom died a natural death. Kings killed their mothers, step-mothers, and children; sisters killed each other. Cleopatra used the same methods, but she lasted longer because she always found a Roman protector. Her brother Ptolemy XIII was killed in battle with Caesar’s troops; and Cleopatra apparently poisoned her next brother/husband, Ptolemy XIV during the period when Julius’s death left her vulnerable. And her visit to Antony at Tarsus was not just about sex; her younger sister Arsinoe had taken refuge in Ephesus, where Cleopatra arranged for Antony to have her killed.*

* Why was Egyptian family politics so treacherous? Marriages that elsewhere would be considered incestuous-- siblings, step-parents-- plus their cold-bloodedness, meant they were without love or personal attraction. This was normal in inter-family political marriages, but here the family itself contained the biggest threats to one’s rule. Cleopatra herself was prolonging the system while also trying to break out of it, sexual politics as alternative to deadly-incestuous family politics. See my post, Really Bad Family Values --- for the origins of murderous family politics among the Ptolemies’ Macedonian ancestors at the time of Alexander. Before the Ptolemies, Egypt had conventional incest taboos, and few royal murders.

Snaring Antony gave Cleopatra safe harbor for a while. He spent a year with her in Alexandria, during which she gave birth to twins. But it was not all non-stop partying for ten years. Tensions between Octavian and Antony were emerging; and Pompey’s forces were still to be reckoned with, especially the warships of his son, Sextus Pompeius, in Sicily and the western Mediterranean. Eventually Antony had to go back to war. He had been allotted the eastern part of Roman possessions, which included Greece, Syria, Palestine, and Iraq, and needed new conquests to keep up prestige and income. Antony was gone four years, returning to Egypt in 36 BC. From then on, Alexandria was his home base, although he was intermittently away on campaigns. Politically speaking, Antony was now leading a double life. In Rome, he was one of the triumvirs controlling the state; but he left his wife Fulvia in charge-- keeping up alliances, raising money and troops for his side. (Cleopatra wasn’t the only woman empowered by a husband’s absences.) In Egypt, Antony and Cleopatra ruled as husband and wife, having married in an Egyptian rite-- even though, after Fulvia’s death, he was also married to Octavian’s sister, in one more effort to patch up their alliance.

Antony’s war against the Parthians in Iraq did not go well; but there were enough victories in Armenia so that he could celebrate a

Roman-style triumph in 34 BC. This in itself was a breach; a triumph was a victory parade through the streets of Rome showing off captives and booty from foreign victories, but Antony celebrated it in Alexandria. It was Cleopatra’s high-water mark. Cleopatra and her son by Caesar-- Caesarion-- were named co-rulers of Egypt. The daughter and two sons of Antony and Cleopatra received titles reigning over possessions respectively in Libya, Armenia and Parthia, the Levant and Asia Minor. This was playing fast and loose with Roman conquests (also some that were iffy, such as Parthia). Antony himself took no titles, but named Cleopatra “Queen of Kings.” Caesarion was being set up for something bigger, as Julius’s son, presumably if Octavian could only be gotten out of the way.

The rest we know. Octavian broke with Antony and defeated him in 31 BC. Octavian pursued him to Alexandria; Antony’s last loyal troops began to switch sides; the rest is suicide. But even at the end-game, there are indications Cleopatra was still maneuvering. Octavian sent feelers to Cleopatra promising good treatment if she would betray Antony; he found out about it and it took some patching up to get them back on loving terms. And there is a suggestion, in Appian’s history of the civil wars, that Sextus Pompeius, having been defeated by Octavian in Sicily, was negotiating for refuge and alliance simultaneously with the Parthian king, with Antony, and even with Cleopatra. Who knows-- a little more room in the timing and Cleopatra might have found herself another protector.

Success-magic charisma: Obviously Cleopatra had no reputation like Caesar or Joan of Arc for always being victorious. But consider her string of recovering from losing her kingdom. She did it twice; first with her father, when he fled to Rome; and again with Julius; preemptively enlisting Antony as her protector was the third time. And she didn’t just rest with getting back to even. She saw the opportunities for much bigger aggrandizement: getting her son Ceasarion named heir to Julius, always an ace in the hole until the very end; getting Antony to crown his own children as kings, not only of former territories of the old Ptolemaic empire, but of Roman conquests in the East. She almost split the Roman empire, making herself Queen of Kings, as Antony proclaimed her. It is one of the world’s great records of almost.

Reputational charisma: She did not exactly have a reputation for being charismatic, except as a personal charmer of the first order. But she certainly was famous. Already around 40 BC, Cleopatra must have been one of the three most famous persons in the western world (along with Antony and Octavian). Even her death added to the fame that made her, almost continuously, the most famous woman leader in history.

Fame per se is not charisma. It has its own causes. To note one here: very famous persons tend to cluster, in networks of acquaintance and antagonism. All four big names of the late Roman republic (we can add Pompey here) were connected, both directly and by 2-link intermediate ties (usually sexual and familial). * They made each other famous. The drama of Antony and Octavian revenging Julius; the drama of Antony against Octavian; the drama of Cleopatra and everybody. Fame multiplies fame, especially since it comes from interaction.

* Pompey was married to Julius’ daughter, while Julius married Pompeia, a relative of Pompey. Octavian was son of Julius’ niece, and adopted by him as his son and heir. Antony was related to Julius on his mother’s side.

Was Cleopatra charismatic?

Yes, in a unique combination of sexual backstage charisma, frontstage spectacle, and political astuteness. She knew how to use spectacle to keep her own freedom of action, since she directed it herself and did not let it turn into an entrapping ceremonial routine.

Is Cleopatra the archetype of distinctively female power? Or an anomaly of special historical circumstances? She seems a premodern figure, of the era of hereditary family rule, with enhanced chances for sexual maneuver while the conservative Roman Republic of elite families was distintegrating into dictatorships.

Could anyone do this in the era of modern democracies-- that is, win power by sexual charm? No doubt we could find examples of the charm, but who could a woman turn it onto? She might captivate a political or corporate leader, but their positions are temporary, not hereditary; and once captivated, what could they do for her? --certainly not give her a kingdom.*

* Ironically, the best opportunities for hereditary charisma today come inside political movements, especially of the left or populist brands. A movement may operate in a democracy (or for creating a democracy from an autocracy), but a leader like Martin Luther King’s wife and children, Nelson Mandela’s wife, or Aung San Suu Kyi or Indira Ghandi or Benazir Bhutto stepping into her father’s or husband’s shoes, is not democratically chosen by the movement. It is the power of reflected charisma or fame, plus having a head start in the magic circle of political visibility, that makes them automatic contenders for the top.

Perhaps surprisingly, women’s access to top power is greatest in conservative and autocratic regimes. In early modern Europe, the best example is Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia. Not a great beauty when she arrived as a German princess, she had the advantage-cum-disadvantage of being married to an incompetent young heir to the throne. The joker in the deck of hereditary rule is that the skills and energies of leadership are not automatically passed on. Weakness is an opportunity for whoever is in position to seize the machinery of organization; and Catherine expanded the modernizing bureaucracy started by her husband’s grandfather, Peter the Great. The danger was assassination and palace coup, which Catherine guarded against via a succession of court lovers, who murdered her opponents, starting with her husband.

Future Catherine the Great at her betrothal, 1746

Women do as well in autocracies as anybody, except generals. When political rulers are careful to keep generals from taking over, the woman closest to the male dictator has a unique opportunity.

And this bring us to:

Jiang Qing, Mao Zedong’s voice

Dozens of Chinese teenagers crowd into a room. They have trapped an official and are demanding that he admit his errors. He is a bourgeois counter-revolutionary, a capitalist roader, a revisionist black-liner, a deviant from the Red line spelled out by the Great Leader, Chairman Mao. They wave the Little Red Book in his face; they tear his shirt; they slap his face. They pressure him relentlessly. It goes on for hours, sometimes day and night, in new shifts. Finally he has confessed, been cross-examined, accused of insincerity, brought out to make his public self-criticism. He is paraded in the streets as the crowd watches, chants in unison, waving their Little Red Books of Mao’s sayings.

It is the Cultural Revolution and this is a struggle session. It happens in dozens of places, then in thousands-- first at universities in Beijing, then government offices, schools, factories, newspapers and radio stations, spreading across the country. Demonstrators split, accuse and attack each other. They have gone too far, they have attacked the wrong person. They are counter-revolutionaries, anti-party groups. No, the accusers themselves are the counter-revolutionaries, bourgeois road-takers, fake leftists. They clash in the streets, invade each other’s schools and dormitories, fortify themselves with barricades. They take prisoners and torture them into making confessions. Such are the scenes in China from 1966 to 1969.

Frontage/backstage merged: It is group charisma, enthusiastic energy that will not be denied. It is based on unity, and casting out disunity. It is done in the name of our great comrade leader Mao Zedong. But he is not here. Struggle sessions proliferate as student Red Guards form spontaneously. Mao is the guiding spirit, but he gives little or no instructions, only slogans, from a distance. There is no chain of command. It is a movement outside all chains of command, designed to purge and purify and eliminate all command.

Everything is done in groups, in moveable public gatherings. Frontstage and backstage are merged; there is to be no backstage where anyone can hide.

Jiang Qing (Chiang Ch’ing) is in at the beginning of the turmoil. In 1965, she and a young newspaper editor criticize a play written by a Beijing official as a veiled attack on Mao. He has been under fire within the communist leadership since 1959, for the failure of the Great Leap Forward, an attempt to spring China into an industrial giant rivaling the Soviet Union, and to abolish all remnants of bourgeois private property. But the communes failed, agriculture fell, famine followed. Mao retired from the government, gave up all offices, retaining only one: Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. He became surrounded by reformers who want trade rather than self-sufficiency and isolation, pragmatism rather than communist perfection.

In 1965 and into spring 1966, Jiang Qing and her allies strike back on behalf of Mao. She had been his wife since 1938 (Mao’s fourth), while communists were protecting their enclave in northwest China, avoiding the Japanese and waiting their time to overthrow the Nationalists. Before that, Jiang Qing (this was her party name assumed at this time), had been a young movie star, until the Japanese overran Shanghai. She had risen from the bottom, her mother a concubine, cast out from her family, degraded to a servant and prostitute; the future Jiang Qing made her way by her beauty and her acting talent, marrying and divorcing a string of men who she met in her progress through school and theatre. Mao soon took up with her, although other Party leaders objected-- Mao was already married to a long-serving Party member who had made the Long March with him. Mao did not yet have the absolute authority of later on; he agreed to marry Jiang Qing secretly, keep her out of public eye, allow her no place in Party affairs for 30 years. Jiang Qing became his private secretary, as backstage as one could be in the CCP.

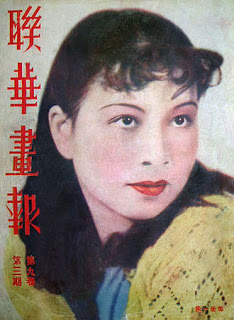

Jiang Qing as film star, 1935

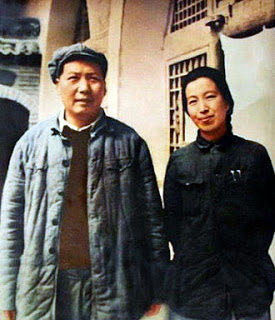

Mao and Jiang Qing, 1946

Now, with Mao 73 years old and fading, Jiang Qing and her followers went on the attack in his behalf. The play, they declared in the press, set in the past about an evil emperor who dismisses a loyal official, was really about a high-ranking communist who has criticized Mao. The play’s official supporters struck back, decreeing the dispute merely an academic matter apart from politics. In May 1966, Jiang Qing renewed the attack: academic matters are no place to hide from political issues of life or death for the Great Proletarian Revolution; such writers and their supporters must be reformed and purged. Mao got the Politburo (central committee of the Chinese Communist Party) to agree. Shortly after, a Beijing University teacher put up the first wall poster attacking the older professors as “black anti-party gangsters.”

So-called “work teams” were quickly sent out by government ministries to investigate and purge the schools and universities, but they served mainly to shatter authority. By mid-summer, student Red Guards exploded into the power vacuum, launching their own struggle sessions. The Cultural Revolution was under way.

Jiang Qing’s position in the regime was merely as head of film and theatre (including the Beijing opera), but a revolution

in culture was being demanded. The material foundations of communism existed but the ideological superstructure remained to be reformed. Young students, born since the 1949 revolution, who had no memory or taint of the old ways, were the best troops for this assault on their recalcitrant elders. Thought reform (what American prisoners during the Korean War had called brain-washing) was their task.

To direct the campaign, the Politburo set up a new committee, the Central Cultural Revolution Group. Jiang Qing was only a Vice-chairman but soon became its real power behind the scenes, since everyone assumed she spoke for Mao-- she certainly acted as if she did. She and three of her protégés came to be known as the Gang of Four.

Mao spoke out only intermittently. At first he mostly praised the actions of the Red Guards. Police were forbidden to interfere with the Red Guards, even when they used violence; the army was forbidden to interfere, then required to cooperate; all students were to be allowed to travel to Beijing, all officials to help by providing free train travel and accommodations. It was at this time that the personality cult of Mao began, with demonstrators carrying pictures of Chairman Mao everywhere, brandishing his Little Red Book (published when he was under criticism in 1964). People’s Liberation Army general Lin Biao came aboard, vying with Jiang Qing as the greatest of Mao’s public adulators, declaring in a speech: “everything the Chairman says is truly great; one of the Chairman’s words will override the meaning of tens of thousands of ours.” As the Cultural Revolution burgeoned into violence and destruction of old temples and religious monuments in the summer of 1966, Mao urged all Red Guards to come to Beijing, where 11 million of them paraded through Tienanmen Square to cheer Mao and Lin Biao standing beside him. Eventually the two names were always used in conjunction in public announcements, “Chairman Mao and Vice-Chairman Lin.”

Jiang Qing and Lin Biao were now allies, initiating fresh attacks on recalcitrant targets. In January 1967, they crushed resistance from China’s second major city, Shanghai, by encouraging Red Guard assaults against all municipal officials, and setting one of the Gang of Four in charge of the city. Next month, Jiang Qing and Lin Biao demanded purges and “class struggles” in the military. Army generals pushed back, but again Mao backed Jiang Qing’s initiative. Jiang Qing was flying from one city to another, addressing mass meetings and denouncing opponents as “counter-revolutionaries.” In July, she went so far as to order Red Guards to replace the army.

The Cultural Revolution spiraled out of control. Local officials mobilized their own Red Guards to combat others, workers took various sides, and the Red Guards based in different schools tended to split and fight against each other. In cities with armaments factories and military installations, fighting was particularly violent, seizing military weapons or embroiling the soldiers. Altogether 1.5 million persons were killed during these years. Many of those who were purged and humiliated committed suicide.

Eventually Mao, realizing the administrative apparatus of the country was being destroyed, ordered the military to stop the Red Guard purges, and sent 18 million youth to work in the remote countryside. Schools and universities were closed. They went off ritualistically at the railroad stations, singing about their new task. It turned out to be farm labor, living in sheds and caves and subsisting on poor people’s food like mushrooms, an exile that would last almost ten years.

Political struggle at the top went into a new phase. In 1969, Jiang Qing was promoted to the Poliburo; Lin Biao moved up to be second-in-command and Mao’s successor. But the Red Guard weapon was gone, and the army had reasserted its indispensability. Zhou Enlai (Chou En-lai), the other famous communist hero from the early days of revolution, was viewed increasingly as a threat. Jiang Qing treated him as a personal enemy; although she could not remove him from his official position as Premier, she made Zhou sign an order to arrest his own brother, and had his son and daughter tortured and murdered, even cremating the body to forestall an autopsy. Meanwhile, Lin Biao was provoking jealousies, including from Mao himself, and probably from Jiang Qing, who was rumoured to be aiming to make herself Chairman of the CCP. By 1971, Lin Biao was being pushed out, and his supporters (notably Lin’s son) launched a military coup. Over a period of six days in early September 1971, there were attacks on Mao’s private train, fended off by guards posted for hundreds of miles along the tracks. Lin Biao with his family fled by plane to Russia. They never made it, the plane crashing in Mongolia in circumstances that have never been explained.

With Mao’s health declining, Jiang Qing’s prominence was at its peak. But political opposition and public hatred of her were building. She and the Gang of Four controlled all news reporting and cultural performances. Pivoting on Lin Biao’s downfall, she launched a campaign called “Criticize Lin, criticize Confucius” which tried to link her former ally with cultural reactionaries, and implicitly with Zhou Enlai.* But the public was exhausted with campaigns of militant communism; exhausted too with forced rituals of pretending to show frontstage enthusiasm for whatever was the campaign of the moment-- and knowing the target could change abruptly.

* Done with typical Chinese innuendo and punning on names, since Zhou had the same name as the Duke of Chou, hero of ancient Confucian texts.

The campaign against Zhou Enlai turned into the downfall of Jiang Qing. When Zhou Enlai died in January 1976, his state funeral spilled over into spontaneous commemorations all over China. The Gang of Four issued instructions in the press against wearing mourning emblems for Zhou, but as a test of control it signalled the wrong result. Deng Xiaoping, soon to take over as the great market reformer, delivered the funeral oration in front of all the Communist leaders except Mao, who was already dying. Again in April, at a traditional festival for the dead, crowds put up posters in Tienanmen Square praising Zhou Enlai, and-- for the first time-- publically criticizing Jiang Qing. One person would read the poster aloud, while the people behind him would form a “human microphone”-- repeating the words in loud voices so that it carried back into the crowd. [Guobin Yang, 148] Security forces made arrests and Deng Xiaoping was put under house arrest. But it was a nervous equilibrium. Mao died on September 9, Jiang Qing at his side. Within a month, she and the Gang of Four were arrested by a special military unit. There were celebrations all over China.

Jiang Qing was imprisoned for 5 years while Deng Xiaoping consolidated power, then put on trial in 1981. Refusing to recant, she had maintained a stoic silence. At the nationally televised trial, she was the only one of the Gang of Four who spoke up. “I was Chairman Mao’s dog,” she said. “I bit whoever he asked me to bite.” Sentenced to death, commuted to life imprisonment, she committed suicide in 1991.

Success-magic charisma

did not cling to Jiang Ching, except during her years of upward ascent between 1966 and 1971 when it was dangerous to challenge her. Being feared is not real charisma, if we define it as the power to move people spontaneously. We could call the entire movement group magic charisma, enthusiastic believers in the infallibility of their collective will. In fact Mao’s policies failed repeatedly, but his Little Red Book was treated like a magic talisman, providing all the answers. And it was dangerous to disregard it. Call it the magic of hope, the magic of a movement armed with an embodied ideology-- they had it in their hands, thousands of hands, visible wherever one went. Their mass mobilization was proof of their magic, the palpable proof of their power over whoever resisted.

In the not-very-long run, it was self-undermining. The movement so certain of its path repeatedly split, each faction lashing out in fear of being labelled on the wrong side of history, until it must have become apparent there was no magic path to success. It was the self-destruction of the egalitarian revolution, like the Reign of Terror in Paris during 1793-94, when the French revolution cannibalized itself.

Reputational charisma: Jiang Qing was only secondarily famous during the Cultural Revolution, since she always portrayed herself as the conduit of Mao’s wishes. She took the most radical initiatives and Mao backed them up, at least for a while; and even when he had to pull back and send the Red Guards into exile, she quietly enhanced her official position and her backstage power. As Mao weakened and his opponents returned, Jiang Qing became increasingly prominent on her own-- all the more so as her main rival in riding on Mao’s image, Lin Biao, became the new target for attack. But now fully in the public eye, Jiang Qing acquired what might be termed negative charisma, as the most hated person in China. Certainly she played the part of arch-villain at the trial of the Gang of Four, defiant to the end. She had once played the lead in Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House, the feminist heroine who walks out and slams the door. This is how she went out in real life: one person who could not be thought-reformed, who would never give in to performing self-criticism.

Jiang Qing and Lin Biao had reflected charisma, in the halo of Mao Zedong. But Mao’s charisma, too, was being created simultaneously during the Cultural Revolution; and they were the stage-managers of his reputation. If the puppet-master was calling the plays, Jiang Qing found she could not entirely control what Mao would do, especially when he had to clean up the destruction she encouraged. What was happening was the joint construction of each other’s charisma, in all its degrees of unreality and the emotional power of collective belief.

Was there any distinctively feminine aspect to Jiang Qing’s charisma? Her early career was made by sexual attraction and the ability to choose partners and change them as a better one came along. Some men attempted suicide when she left them. This may have been a reason why the early communist leaders were unwilling to let Mao marry her. Late in life, Mao had a quasi-harem of younger women, no doubt downgrading Jiang Qing’s strictly erotic position. * But she had been his private secrtary, keeper of his closest secrets, and the most politically adept of Mao’s wives and lovers. In this respect, Jiang Qing resembles Cleopatra.

* It was rumoured that Mao and Jiang Qing had separated in 1973, although it was never announced, and she continued to play on her reputation as Mao’s wife.

Better than anyone, Jiang Qing was able to ride on Mao’s image and manipulate it to her own ends. She lasted longer and did better than the famous general, Lin Biao. This must have come from her intimate tie with Mao. Sex, love, a long career of living closely together-- nothing could put someone in a better position to claim to channel a great leader’s wishes.

The question once again: when are women charismatic leaders?

Jiang Qing was not the only prominent woman in the Cultural Revolution. Nie Yuanzi, a young philosophy instructor at Beijing University, put up the first wall poster that sparked the movement. She became leader of one of the biggest Red Guard groups in the city, chaired a Red Guard unity congress, and attempted to take over Beijing the way Red Guards had overthrown the municipal goverenment in Shanghai. [Walder, 279] But her group was badly split by violence inside her own university, some of which she ruthlessly ordered herself. She was criticized for being dictatorial, and Jiang Qing had to intervene to save her. The communists were pursuing a unisex policy at this time, men and women dressing alike -- and taking identical, non-gender-marked names. There were a number of women among Red Guards leaders, although men predominated. The radical revolutionary atmosphere favored some gender equality in the leadership, but Jiang Qing did better than other women, with her double sources of power.

Joan of Arc lived at the cusp of a big structural transformation, the end of feudalism and the rise of the modern state. It is in just such locations in history where the biggest names are made.

It was also virtually the last time battles were won by charging the enemy with hand-arms. Cannon were beginning to come in, and would be used not just in sieges to batter walls but to sweep battlefields, along with musquet fire. Castles were being replaced by organization and logistics. Joan, the leader with a sword-- really, the leader with the banner followed by the swords-- was near the end of the time when anyone could lead by sheer inspiration from the very front of the troops.

Cleopatra, too, lived at a time of structural transformation. This may be the underlying logic in the fact that the other candidate for the most famous woman of all time-- Mary, mother of Jesus-- was born in the next generation after Cleopatra, and within a few hundred miles of each other; Judea being one of the satellite kingdoms in the Ptolemaic empire, taken over in the Roman conquest. Super-fame comes from being in on the action of important people, however that is read by following generations. Cleopatra is the end of something, Mary and her son the beginning of a more universal movement, facilitated by a universal empire. Being a charismatic leader means taking a very active part in the action. Cleopatra did that, in a spectacular way that makes her particularly memorable as a political woman. If her political skills are veiled in her erotic reputation, that is appropriate, since that was how she presented herself. Sex is probably a universal resource, but also a liability.

Cleopatra knew how to use the political iron hand in the sexual glove, a move that was more structurally available to women in a time of hereditary family dynasties.

Where does that leave us? The conditions that made Joan of Arc and Cleopatra possible no longer exist. Jiang Qing, who has some resemblance to Cleopatra’s methods but wrapped in a Mao jacket, shows what remains-- at least in the vehement form of charisma in the midst of dangerous and radical movements. As I noted, stable democracies do not seem to be very good for women’s dramatic domination on the political stage. If it is to be found, look for periods of turmoil where backstage politics meshes with turmoil in the streets.

“Collins has channeled his deep knowledge of human violence and the intricacies of combat into a taut and compelling what if fantasy that takes the cultural fissures of our nation to full scale rupture."

– Alice Goffman, author of On The Run: Fugitive Life in an American City

CIVIL WAR TWO Available now at Amazon

References

Jules Michelet. 1853/1957. Joan of Arc.

George Bernard Shaw. 1924. Saint Joan: Preface.

John Keegan. 1976. The Face of Battle.

Cambridge Modern History. Vol. I. 1907.

Chambers Biographical Dictionary.

Randall Collins. “Jesus in Interaction: the Micro-sociology of Charisma”

Plutarch. Life of Caesar; Life of Antony.

Julius Caesar. Gallic Wars; Civil Wars.

Appian. The Civil Wars.

Robert Morkot. 1996. Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Greece.

Randall Collins. "Really Bad Family Values."

Wikipedia. Cleopatra VII.

Andrew Walder. 2009. Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement.

Guobin Yang. 2016. The Red Guard Generation and Political Activism in China.

Wikipedia. Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution; Jiang Qing.