What does a dictator look like in action?

There is a distinctive pattern, but it is visible not so much on the dictator’s own face as in the expressions of the persons surrounding him or her. (Since all the dictators that I know about and have photos of are men, I will use the male pronoun.)

The dictator is the center of rapt attention. It is compulsory to look at him, and dangerous to show any emotional expression other than what the dictator is displaying. Faces surrounding a dictator mirror his expressions, but in a strained and artificial way.

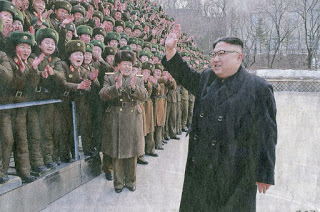

Let us examine a series of photos of Kim Jong Un, the North Korean dictator.

Kim Jong Un smiles a lot for the crowd, but that isn’t the striking thing. His smile is pallid and not very warm, but the people around him are fervently smiling and applauding. They are putting a lot of energy into it, trying to smile as hard as they can.

These are forced smiles. As psychologist Paul Ekman has shown in detailed studies of the facial muscles used in different kinds of emotions, smiles vary a great deal in intensity and spontaneity. (For examples, see my blog Mona Lisa is No Mystery for Micro-Sociology.)

Fake smiles can be easily detected, as can the other emotions they are blended with. As we shall see, faces around a dictator blend the required expression with give-away signs of tension, anxiety, and fear.

It happens with all ranks. In the following photos, Kim Jong Un’s rather perfunctory smiles are amplified by his intently attentive generals, foot soldiers, and military women alike:

Conversely, when Kim Jong Un isn’t smiling, nobody smiles. When he is serious, everyone looks serious. Surrounding faces mirror his expression as best they can.

And mirror his body postures too:

Occasionally we see nervous eyes, like the man directly behind

Kim Jong Un, glancing sideways to monitor what he is supposed to display:

Or the man who bites his lip, peering forward to catch the dictator’s expression as he telephones an order:

The pattern is the same with the previous dictator,

Kim Jong Un’s father, Kim Jong Il:

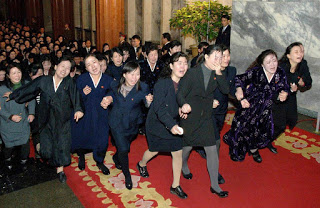

The most exaggerated expression is the safest: Kim Jong Il’s funeral

Photos of Kim Jong Il’s funeral, after his death in December 2011, show extraordinarily demonstrative expressions of grief, among all social groups:

Well, almost all social groups. In the following photo, the well-dressed women of the North Korean elite show the most intense grief, as they reach the top of the red carpet. Further back in the queue, postures are more restrained, and the guards and attendants along the side are stolid and unexpressive.

A notable exception is Kim Jong Un himself, who shows no grief but looks a little worried.

The over-the-top expressions of grief are confined to the North Koreans. Photos of foreign dignitaries at the funeral show them somber and respectful, bowing politely but showing no strong emotions, let alone such ostensibly heart-rending displays. These are not normal behavior at East Asian funerals.

Compulsory Front-stage performance of loyalty

We have seen the pattern. People around the dictator, and particular those of high rank, mirror his expressions and re-broadcast them at even higher intensity. They put a lot of effort into it, so that their expressions look forced and unnatural. They look over-the-top. The dictator himself doesn’t look strained, but the people around him do.

Their expressions are not merely for the eyes of the dictator. He doesn’t, on the whole, appear to be giving them too much attention. Their expressions are for each other, broadcasting the message that they are buying into the show as strongly as possible. They are always on-stage for each other, sending the message of loyalty to the dictator. It is a competitive situation, to show who is most loyal of all.

The competition is strongest among the elite—those closest to the dictator—because these are the persons who pose the greatest potential threat. Quite likely there is an atmosphere of suspicion and denunciation, as jockeying for power and favor takes place by detecting signs of disloyalty among his followers—or even just lack of enthusiasm. *

* A former student of mine, who had been a teenage girl at the time of the Red Guards movement in China, told me that the hardest thing about the omnipresent public demonstrations was keeping up the tone of fervent enthusiasm. It was dangerous not to; it could get you pilloried as one of the counter-revolutionaries. When I introduced this sociology student to Goffman’s concepts of frontstage and backstage, she immediately characterized the most onerous part of the Red Guards movement as the compulsion to express extreme emotions that one didn’t really feel--you were always on stage.

This is why we see such extreme expressions of grief at the dictator’s funeral—a time of most intense jockeying for power in the succession.

The succession crisis of dictators

Even when there is a family succession, a de facto hereditary dictatorship, there is tension. The oldest son does not necessarily succeed (Kim Jong Un was the third son of Kim Jong Il), since the father may weigh who is most competent at wielding power. Photos of father and heir show a distinctive pattern:

Here we see Kim Il-sung, founder of the North Korean regime, and his son Kim Jong Il. The son is mirroring the smile and body posture of his father, although older man looks confident and at ease, the son more tense. We see the same again in a photo of Kim Jong Il as dictator, with Kim Jong Un as heir apparent:

The following photo, taken in the last year of Kim Jong Il’s life, is revealing because of the elite audience watching the interaction between father and son.

Kim Jong Un is leaning deferentially towards his father, showing the uncertainty and touch of anxiety he often showed in his father’s presence.

Faces of the onlookers who can see both of them most clearly have a wary look. One man is pursing his lips to one side, giving a distorted look to his face (Ekman notes that an asymmetrical face, showing different expressions on different sides, is a sign of mixed or conflicting emotions.)

The onlookers don’t quite know who they should be mirroring here:

Why close is dangerous

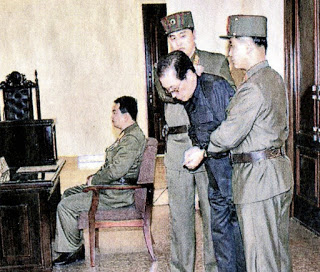

In a dictatorship where loyalty is always suspect and must be constantly demonstrated, those nearest to power are the most dangerous. This was illustrated within two years of Kim Jong Un’s formal succession. His uncle, Jang Song-thaek, 40 years older than the young heir, acted as informal regent. The following picture, taken during that early period, suggests guarded suspicion between the two:

By September 2013, however, Kim Jong Un was leading the public smiles, and his uncle was following along:

By December 2013, the uncle was arrested, tried, and executed. Reportedly, he had plotted a coup. Or perhaps he just aroused suspicion, by not giving off the right emotional displays. Soon after, the rest of the uncle’s family apparently were executed too.

Since then, an older brother was killed.

And the dictator is back to smiling, surrounded by the wary, mirroring faces that characterize the dictatorship:

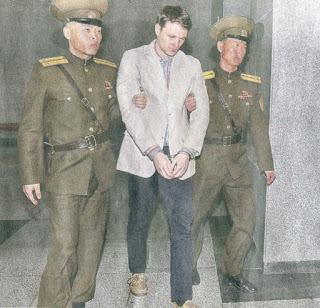

American tourists, too

The photo of American tourist Otto Warmbier being brought into court for sentencing in March 2016, after two months in captivity, closely resembles the photo above of Kim Jong Un's uncle

Jang Song-thaek

being led into the same court in 2013, just before he was executed.

In both cases, the arrestee shows the same posture: hopeless downcast eyes, body slumping in extreme depression. Undoubtedly they had been put under relentless psychological pressure to confess, and probably physical torture.

Their offenses, at least initially, were different: Jang Song-thaek was charged with staging a coup d'etat; Otto Warmbier with defacing or attempting to steal a government propaganda poster from his hotel just before he got on the plane. After Warmbier was released in a coma from which he never recovered, a North Korean official said his punishment was for trying to overthrow the regime.

Most likely, Otto Warmbier, acting like an American college student on vacation, was trying to collect a souvenir poster (the way we used to take bullfight posters or beer coasters).

But youthful pranks are not recognized in the official culture of the North Korean dictatorship. Every expression is deadly serious in its consequence, and every individual is under suspicion.

In such regimes, there is no private life and no backstage fun and games.

Disrespecting a symbol is taken as an attack on the regime it symbolizes.

What can be done? That is a complicated political and military problem. It would be an enormous step for the regime to loosen up, just to allow a space for trivial matters.