Classic fantasy is a cross-over: children’s literature for adults too. Star examples of the category are the Alice in Wonderland books (1865 and 1871), the Wizard of Oz books (1900-20), the films made of both (1939, 1951), the cartoon films Yellow Submarine (1968) and Miyazaki’s masterpiece, Spirited Away (2001). All are parts of an ongoing sequence, which is how classic fantasy gets created.

How did Lewis Carroll go about writing Through the Looking Glass, after writing Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland? By transforming the earlier book into the later. The materials that made up Alice get used again, with different variants and characters. The first book’s plot action -- to the extent that it has a continuous plot-- is driven by playing cards come to life; the second book makes each chapter a move in a giant chess-game. In Wonderland, Alice grows larger and smaller; in Looking Glass, Alice experiences reversals in space and time; for instance, since she is in a mirror universe, she can never get somewhere by walking straight toward it, but must go in the opposite direction. Other elements, such as Alice’s frustrating conversations with the fantastic characters she meets, continue through both books. The later text is made by reversing and recombining devices from the earlier text.

All books are sequels to something. An author can write another book; new books can be created by new authors using previous authors’ devices. I will proceed on the plan that there is no real difference in the methods of creative recombination used when an author creates a sequel to a successful book, or when an author creates a successful sequel to someone else’s books. There must be millions of readers who started out to imitate a classic book; but we don’t know much about the failures outside the few that succeeded. In self-sequels, we have the advantage that a famous author will have followers who dig up their lesser and failed works as well.

Why care about minor failures when we can focus on the great works? Because both were produced by a similar creative process. Comparisons illuminate causes. We can trace how Lewis Carroll wrote Alice in Wonderland but also Sylvie and Bruno; and why L. Frank Baum was a long-term success at Oz books, not at Oz films, nor his other fantasy books. We hold constant the author and social setting, and isolate the technique of making a success in the fantasy classic niche.

Generic features

The classic crossover fantasy genre uses these devices:

An alternative universe or magic garden, entered by a portal from the ordinary world. Alice goes down a rabbit hole or through the mirror over the mantlepiece; Dorothy’s house is carried away in a tornado; the Beatles are picked up from Liverpool in a yellow submarine; Miyazaki’s child-heroine goes through a tunnel into an abandoned theme park. The Chronicles of Narnia start when a child pushes through the clothes at the back of the closet.

The magic portal is a modern device; traditional fairy tales just start in the enchanted world, and their protagonists live there happily ever after instead of returning to an ordinary home. In the era of religion when magical ritual was practiced daily, there was no banal ordinary world from which to leave. Banality came with the disenchantment of the world by commerce and bureaucracy that defines modernity. It also created a platform for portals to an alternative universe.

A naive child protagonist, especially a little girl. This sets up the possibility of cross-over effects, where the mature reader can see things in the text that the protagonist does not understand. The writer can play around with spacey philosophical concepts, like time speeding up or going backwards.

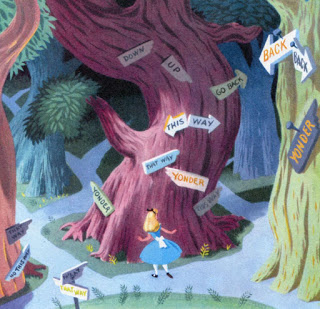

Quasi-meaningful humorous nonsense. Lewis Carroll likes to use verbal misunderstandings, nonsense words or verse. Films can do nonsense in images, like direction signs pointing every way at once (used in both the 1951 Alice and in Yellow Submarine).

A picaresque plot line: a series of discrete adventures strung together by the protagonist on a journey. Picaresque is a very old plot form, going back to the Odyssey and the Voyage of the Argonauts. It is convenient for packaging a collection of older myths and characters. The picaresque structure of classic fantasy makes the genre especially inviting to repackaging earlier classics-- a central method by which each new version is created.

Other major literary forms are not picaresque: tragedies are a compact web of characters tied by strong emotions-- just the opposite of the light and carefree tone of children’s classics.* Situation comedies, too, tend to be in the real world and play on a repeatedly interacting web of characters. Picaresque is especially suited for fantasy; introducing more complex character interaction into it is usually a way to make it fail-- as we shall see from Lewis Carroll’s failed efforts.

* A naive child protagonist also rules out sex in the plot. There is a slight love-interest in Spirited Away, between the heroine and her boy-ally (who is also a dragon, thereby cutting out erotic possibilities, unless you wanted to get really kinky). This isn’t bowdlerizing, but the ingredients of the genre. In Yellow Submarine, all the named characters are male; John’s erotic fantasy “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” is very tame and subject to other interpretations. Spirited Away is set in a pre-modern bathhouse; this is modeled on the luxury brothels of the Yoshiwara district of pre-modern Edo, but there is no hint of prostitution in the film version.

If you lived in 1860, or 1900, or 1965, or 2000+, how would you create a new fantasy classic? By following these generic techniques, adding new materials, and recombining.

Upstream from Lewis Carroll

How did Charles Dodgson, Oxford mathematics lecturer, create the first Alice book? By telling a story to three little girls rowing a boat through the neighbouring countryside. The story must have begun by imagining a rabbit in the nearby meadow, dressed like a human, holding a watch and disappearing into a rabbit-hole that turns into a deep well, with more adventures at the bottom. It took Dodgson almost two-and-a-half years to complete the book, adding episodes later on like the Cheshire Cat and the Mad Tea Party. Presumably he expanded the dialogue, with its double-leveled nonsensical repartee, and wrote verses that parody older children’s rhymes.

Like most successful creators, he was already in a network of important people: the Pre-Raphaelite painters; high-society persons who provided unwitting material and spread his reputation; a writer of children’s fairy-tales who acted as a sounding board; links to a prestigious publisher. * Looking for an illustrator, he enlisted John Tenniel, the political cartoonist for Punch, England’s leading satirical magazine -- guaranteeing an adult cross-over. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was no casual production, but heavily worked-over.

* C.S. Lewis, who wrote the Narnia series (1950-56), and his friend J.R. Tolkien, who wrote The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings series (1937, 1954-5) were, like Dodgson, Oxford Fellows. Cross-over fantasy became something of a local specialty in this network.

What was the literary upstream that Dodgson/Carroll could draw upon in 1862-4?

Most immediately, Edward Lear, whose Book of Nonsense came out in 1846, when Dodgson was 14 years old. The book was very popular, a break-out book for the genre. It contained the kind of materials that young Dodgson would use in family entertainments, and in poems he published in magazines for children in the 1850s. The 1840s were the decade literary nonsense took off in Europe, especially in Germany, considered at the time the center of avant-garde intellectual life. In 1844 Heinrich Heine, Germany’s most popular poet, published “Symbolik des Unsinns” -- “symbolism of non-sense”. In 1848, Ludwig Eichrodt set off a wave of humorous cartoon-illustrated poem sequences; followed in 1865 by Wilhelm Busch, an artist-turned-cartoonist who wrote the wildly popular bad-boy poem-stories Max und Moritz. German philosophy, science and literature were very much in the English eye, and not only because Queen Victoria had married a German prince. The middle-class publishing market was exploding as schooling expanded; children’s literature became simultaneously more child-centered rather than a vehicle for adult moralizing, and more sophisticated, with an ironic tone that appealed also to adults.

This ironic-reflexive turn built on the older generation of children’s poems, which it recycled through parodies, generally much more palatable and amusing than the originals. Lewis Carroll’s technique, in each chapter where Alice meets an odd character, is to have someone recite a poem, which invariably would be familiar verse turned on its head. Carroll mainly does this in chapters where not much physical action is happening (like falling down the rabbit hole or playing croquet); his standard method in the static chapters is conversation at cross-purposes, plus reciting poems. This replicated a popular domestic entertainment in Victorian households, in an era before recordings or electronic media of any kind, when children of Alice’s age were trained to memorize verses for such occasions. Carroll simultaneously makes fun of polite manners (literally making it more fun), and of the contents of older children’s literature.

Thus the caterpillar makes Alice recite “Old Father William” (a poem by Robert Southey originally published in an Evangelical Christian magazine, and full of pious platitudes); Alice’s version comes out garbled, replacing the adult voice with what henceforth could be called “childishness.” The larger movement shared by Edward Lear, Wilhelm Busch, and Lewis Carroll, is part of the modern invention of childhood. *

* Mother Goose Nursery Rhymes were first published in the 1780s. Many of them originated as satirical political poems for adults, before being transformed into purely children's entertainment. Humpty Dumpty, for instance, refers to a battle in the War of the Roses. These rhymes became part of Carroll’s upstream poetic capital.

The next chapter, a visit to a kitchen where a Duchess is sneezing and nursing a baby, features a lullaby that involves shaking the baby rather than soothing it:

Speak roughly to your little boy,

And beat him when he sneezes:

He only does it to annoy,

Because he knows it teases.

The baby howls and the adults join in the chorus:

Wow! Wow! Wow!

The satire (of a poem called “Speak gently to your little boy”) is certainly on the adults here, although the edge is taken off when the baby is transformed into a little pig that wanders away. The Duchess is the first really negative character in the book; she reappears later, both in person and as the prototype of the Queen of Hearts. This is the formula for the genre: the villains are (more or less human) adults, the protagonists children, their helpers transformed animals or magical creatures, plus silly quasi-adults.

How semi-meaningful nonsense poems are constructed

These examples are made nonsensical by changing some words into their opposites. A more advanced form of nonsense is “Jabberwocky,” which Carroll introduces at the end of the first chapter of Through the Looking Glass. Alice has found a book which she can’t read, until she holds it up to the mirror so the direction of the letters is reversed.

Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

How does one create successful nonsense, that is, nonsense that is enjoyable? By partial transformation, making it semi-meaningful. The first stanza, without the strange words, would read:

Twas [adverb], and the [adjective] [plural noun]

Did [verb] and [verb] in the [noun] :

All [adjective] were the [plural noun],

And the [adjective] [plural noun] [verb].

The poem is obviously English, with conventional grammar; even the nonsense words follow standard forms for plurals, for instance. And the elements of the nonsense words are English syllables-- not Japanese or some other language-- so that the reader can call up word associations for something like “mimsy.” The poem is further structured by its lively four-beat rhythm and its easy rhyme scheme, which the nonsense words strictly follow.

Half the words in the first stanza are nonsense, but it gets easier in the other stanzas. The next stanza, for instance,

Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!

-- has only four nonsense words, and three of them are obviously names of fantasy animals (supported by the accompanying drawing). The fourth, “frumious” is anybody’s guess, but on the whole the rest of the poem is easy to follow, mostly English with a smattering of nonsense words to give a whimsical tone to a rather conventional dragon-slaying story.

A nonsense poem is not something to decipher. It has no intended meaning. The author’s intentional work of constructing it is to make just these kind of substitutions in an otherwise strict poetic frame. Much of its appeal is its word-music. Compare a straight version, Shelley’s To Night:

Swiftly walk over the western wave,

Spirit of Night!

Our of the misty eastern cave

Where all the long and lone daylight

Thou wovest dreams of joy and fear

That make thee terrible and dear

Swift be thy flight!

Shelley makes more sense than Jabberwocky, but it is mostly mood, blended with the word-music. The all-out nonsense poem creates its pleasure out of silly distortions that fit the word-music anyhow.

Nonsense literature depends on using strict forms into which on-the-edge-of-meaning nonsense can be inserted. This implies it is easier to write successful nonsense poems by altering very formal verse than it would be in loose modernist poetry. Would a nonsense version of T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland be appealing to anyone? At most, to a very esoteric audience of specialists. Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, downstream in this technical tradition, tends to prove the point.

Creating episodes

Carroll creates one episode after another using the same formula. Alice encounters an odd character-- a mouse her own size, a caterpillar smoking a hookah, a frog dressed as a footman, a cat that floats in the air, a duchess, a pack of live playing cards; in the sequel, flowers that talk, nursery rhyme characters like Tweedledum and Tweedledee or Humpty Dumpty, chess pieces come alive.

They converse at cross-purposes. Alice always tries to be polite and mind her manners as she has been taught, but it never goes well. To the Mouse she tries to make conversation about her pet cat and gets an outraged response. The Caterpillar answers all her efforts abruptly: “I don’t see.” “It isn’t.” “Who are you?” When Alice tries to explain, “one doesn’t like changing so often, you know.” The caterpillar responds “I don’t know.” Figures of speech are taken literally. When Alice tries to get the attention of the frog footman with “How am I to get in?” he answers, “Are you to get in at all? That’s the first question, you know.”

“It was, no doubt: only Alice did not like to be told so. ‘It’s really dreadful,’ she muttered to herself, ‘the way all these creatures argue. It’s enough to drive one crazy!’

The footman goes on: "‘I shall sit here, on and off, for days and days.’

“ ‘But what am I to do?”’ said Alice.

“ ‘Anything you like,’ said the footman.

“ ‘Oh, there’s no use talking to him,’ said Alice desperately: ‘he’s perfectly idiotic!’ And she opened the door and went in.”

And so it goes. Alice keeps on trying to be polite, gets snappish replies, and loses her temper a bit. The Mad Tea Party ends:

“ ‘Really, now you ask me,” said Alice, very much confused, ‘I don’t think---’

“ ‘Then you shouldn’t talk,’ said the Hatter.

“This piece of rudeness was more than Alice could bear: she got up in great disgust, and walked off.”

It gets worse. She meets the Queen of Hearts, with her constant refrain “Off with their heads!” In Through the Looking Glass, Alice starts off in a beautiful flower garden, where the flowers criticize her manners and appearance. Finally Alice says, “If you don’t hold your tongues, I’ll pick you!” Tweedledee and Tweedledum answer most of her efforts with “Nohow!” and “Contrariwise.” Humpty Dumpty contradicts whatever she says.

“ ‘Don’t stand chattering to yourself like that,” Humpty Dumpty said, ‘but tell me your name and your business.’

“ ‘My name is Alice, but---”

“ ‘It’s a stupid name enough!’ Humpty Dumpty interrupted impatiently. ‘What does it mean?’

“ ‘Must a name mean something?’ Alice asked doubtfully.

“ ‘Of course it must,’ Humpty Dumpty said.”

At the end of the chess game, when Alice reaches the last square and is promoted to Queen, the plot tension of the story is over. Carroll winds up with a final episode: the White Queen and the Red Queen refuse to recognize her as another Queen (“ ‘Speak when you’re spoken to!’ the Red Queen interrupted her.”) until she has passed “the proper examination.” This becomes a parody of school quiz: “ ‘Can you do division? Divide a loaf with a knife-- what’s the answer to that?’ ” Alice gets everything wrong. When the chess Queens invite each other to a dinner-party Alice is giving, Alice objects that she should be the one doing the inviting, and the Red Queen replies “ ‘I daresay you’ve not had many lessons in manners yet!’ ” She finds a door marked “Queen Alice,” but the frog footman (reprising the earlier version) is very unhelpful:

“ ‘To answer the door?’ he said. “What’s it been asking you?’

“ ‘I don’t know what you mean,’ she said.

“ ‘I speaks English, doesn’t I?’ the Frog went on. ‘Or are you deaf? What did it ask you?’

“ ‘Nothing!” Alice said impatiently. ‘I’ve been knocking at it!’

“ ‘Shouldn’t do that--’ the Frog muttered. ‘Wexes it, you know.’ Then he went up and gave the door a kick with one of his great feet. ‘You let it alone,” he panted out, ‘and it’ll let you alone, you know.’ ”

The dinner party is a grand ensemble of animals, birds and flowers. The two Queens flank Alice at the table and shout orders.

“ ‘You look a little shy: let me introduce you to that leg of mutton,’ said the Red Queen. ‘Alice---Mutton: Mutton---Alice.’ The leg of mutton got up in the dish and made a little bow to Alice.

“ ‘May I give you a slice?’ she said, taking up the knife and fork.

“ ‘Certainly not,’ the Red Queen said very decidedly: ‘it isn’t etiquette to cut any one you’ve been introduced to. Remove the joint!’ And the waiters carried if off.”

Alice is hungry and defies the Red Queen by cutting a slice of the pudding.

“ ‘What impertinence!” said the Pudding. ‘I wonder how you’d like it, if I were to cut a slice out of you , you creature!’ *

“ ‘Make a remark,’ said the Red Queen: ‘it’s ridiculous to leave all the conversation to the pudding!’ ”

* This is repeated in Wizard of Oz, when a tree resists having its apples picked, retorting, “How would you like it if someone pulled something off you?”

The dinner turns into a version of the Mad Tea Party, with the guests lying on the table and the food and dishes walking around. So Alice ends the story just as she does at the end of Wonderland, standing up and shaking everything off, and then waking up.

Each episode combines conversational etiquette that fails through the interlocutors’ rudeness, wordplay, deliberate misunderstandings of figurative expressions and multiple meanings. This would likely become annoying to the reader except that Carroll lightens it with parodies and puzzles.

Here the deeper level of these books comes in. For instance, midway through Looking Glass, Alice goes into a shady woods where nothing has a name. She can’t think of her own name, except “ ‘L, I know it begins with L!’ ” She meets a Fawn but it can’t tell her what it is called either: “ ‘I’ll tell you, if you come a little further on,’ the Fawn said. ‘I can’t remember here.’ ”

Dodgson/Carroll, the Oxford logician, creates his most memorable lines for adult readers in this way. Humpty Dumpty: “ ‘When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean-- neither more nor less.’ ‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’ ‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master-- that’s all.’ ”

Carroll’s formula throughout is to transform familiar things into fantasy objects. This is undoubtedly how he created the first version of his tale to the girls on a picnic. The rabbit they see in the meadow becomes dressed up and acts like a human; when Alice falls down the rabbit hole it is meant to take a long time, so he describes things she sees on the walls as she falls: cupboards, book-shelves, maps and pictures; she takes a jar of Orange Marmalade and puts it back. These are rooms in an upper-middle class home; the beautiful garden that she tries to reach is one of the Fellows’ gardens hidden behind college gates and reserved for College Fellows like Dodgson.

On the whole, these are beautiful settings of a leisure society, with even an aristocratic side when Duchesses and Queens come in. They are the chief villains moving the plot (the upper-middle class looking upwards with a critical eye at the declining monarchy). All the activities are polite middle class pastimes-- tea parties, lawn croquet, conversation, poem recitations, cards and chess games, formal dinners and speeches. It is a very nice world, probably above the social experience of most readers. In reality this familiar world is somewhat boring; the fantasy transformation makes it delightful.

Dodgson/Carroll creates his ideas, episode by episode, by taking things in his own familiar environment-- the meadow, the garden, children reciting poems in family parlors-- and applying his transformations: English-speaking non-humans, failed etiquette, double-meaning conversations, and parodies of past children’s literature.

Alice in Wonderland is more memorable than Through the Looking Glass. He launches his first effort with the device of growing smaller and larger, and then repeats each half a dozen times altogether; this supplies more dramatic action than in the later book; and it leads naturally to the denouement where full-size Alice can declare “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”

The chess game provides little plot tension, and the second book’s episodes tend to recapitulate the devices of the first. But the pair of books were crucial in supporting each other’s reception. Alice in Wonderland was well received, but it didn’t become a children’s classic-- nor an adult cross-over -- until after Through the Looking Glass was published 6 years later. With less action, it focused attention more on the embedded philosophical puzzles. As often happens, one great book makes another great-- the formulation does not beg the question, if one thinks of the feedback processes by which literary reputations are made.

Lewis Carroll’s failures

One sequel was a great success. Lewis Carroll tried for another, and failed. Between Alice (1865) and Looking Glass (1871) he wrote a couple of short stories (1867) about fairy characters called Sylvie and Bruno. But he kept this material separate when he produced Looking Glass as a pure sequel to Alice. By 1874 he was projecting a longer book called Sylvie and Bruno, but was unable to complete it until 1889, by which time it was so long that he had to split it into two volumes, the second appearing in 1894. Alice, which took 2.5 years to write, was a great publishing success; Sylvie and Bruno, which took 20 years, was not. Not surprisingly, since the first flowed better and was carefully crafted, whereas the latter was a struggle. Of course, Rev. Dodgson still had his day job, and published on advanced topics from the world of German mathematics during these years; but that was true in his Alice years as well.

Why did Sylvie and Bruno fail? It violated the rules of the fantasy classic genre listed above.

(1) An alternative universe entered by a portal from the ordinary world. In Sylvie and Bruno, there are at least two alternative worlds: Outland, which resembles an Oxford college; and Fairyland, a true magic garden. There is also a real world, with a plot involving a sick man, a doctor, and an aristocratic lady and the choices she goes through in getting married. The story line switches among these worlds numerous times: when the narrator (the sick man) falls asleep and dreams an alternative world (making explicit the framing device that Carroll used at the end of both Alice books); sometimes he dreams a song, containing a character who knows a portal into a magic garden; sometimes the narrator travels on a train from London to the countryside, where he reaches some fairy-land destination (a device used in the Harry Potter stories.) Favored characters can also enter Fairyland by an Ivory Door in a professor’s study, and by other transformations.

Outland is a place where the head of the College, here called the “Warden”, is overthrown in a plot by subordinate college officials called the “Chancellor” and the “Sub-Warden.” This is a satire on academic politics; C.P. Snow (who was a Fellow of a Cambridge college) wrote a straight version in The Masters (1951). The ousted Warden is the father of Sylvie and Bruno; they all get promoted into fairy characters when they are in Fairyland (where the Warden is the Monarch). This gives a two-layer ranking of imaginary characters who sometimes become fairy characters. Dodgson/Carroll was still squeezing his Alice materials, since the real-life Alice was the daughter of his own College head.

The failure of Sylvie and Bruno points up something that was only implicit when I listed the generic features above. An alternative universe from the ordinary world needs to be a binary; too many different worlds, and too many portals connecting them, is psychologically unsatisfying for the audience. As I argued in the case of Jabberwocky, successful nonsense poetry needs to insert its nonsense into a strict frame.

(2) A naive child protagonist. In Sylvie and Bruno, there is a major child character (Sylvie), although she isn’t very naive; and she only intermittently appears. Much of the story is told from the point of view of the narrator, a real-life adult, who not only dreams part of the story but also travels around in several of the worlds. Without a naive protagonist, the possibility is eliminated of having things happen “over her head” that an outside audience can see in more sophisticated perspective. Instead, there is much more explicit discussing and explaining, which ruins the light touch and eliminates much of the humor.

(3) Quasi-meaningful humorous nonsense. Carroll continues to provide material of this sort; for instance one of the professors has invented a time-travel machine, leading to paradoxes about time reversal. [Carroll wrote this only a few years before H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine (1895) used the same device more successfully by constructing the entire plot around it.] Unlike the Alice books, here the nonsense episodes are not linked to non-human characters, talking animals, birds, insects, flowers, and nursery rhyme characters, but are conveyed by conversations among adult humans.

Some of the clever nonsense is successful: a series of maps of increasing scale, so that a map becomes as big as the land it depicts; a government in which thousands of monarchs rule over a single subject instead of vice versa. The adults’ stories satirize academic reforms then going on in Oxbridge: giving scholarships to outstanding students leads to college competing for them and eventually chasing students in the street to give them money. Another story satirizes a professor whose lectures no one can understand; so his students memorize his lectures and repeat them to their own students when they become professors, ending up with a profession teaching something that no one understands. This sounds like a reaction to German Idealist philosophy, which in the 1870s and 80s dominated Oxford philosophy, notably under T.H. Green and F. H. Bradley.

Parts of Sylvie and Bruno thus resemble the more sophisticated parts of Gulliver’s Travels, but they cease being cross-over fantasy for children and adults.

(4) A picaresque plot line. Some of Sylvie and Bruno is picaresque wanderings, but the book’s failure brings out a hidden point: picaresque strings unrelated episodes together because a single character’s travels holds them on a thread. This is the pattern for Odysseus, Don Quixote, Gulliver, and Alice. But Sylvie and Bruno follows too many lead characters, removing the psychological unity of the picaresque.

(5) The failure of Sylvie and Bruno brings to light another principle of classic cross-over fantasy: avoiding direct or prolonged treatment of serious themes. Sylvie and Bruno intrudes these into both plot and conversations. The real-world characters have marriage engagements, but they break up over serious issues like disagreement over religious beliefs. Fantasy, when it does have love interest, makes the obstacles simple and magical, as in Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella . Fantasy may allow a magic sickness, which ends with a magic cure; Sylvie and Bruno has a real-life epidemic and a heroic doctor who sacrifices his life to treat its victims.

It also features morality tales: a boy caught stealing apples; a drunken workman, reformed by Sylvie who gets him to give up drinking and take home his wages to his wife. She is not a very fun fairy. (Not at all like Peter Pan, a successful sequel in this genre in 1904, about a boy who refuses to grow up.) And there are lengthy discussions, both in the real world and the fantasy worlds, of topics like whether animals have souls, what people will do in the afterlife, how the Sabbath should be celebrated, what circumstances make sins more serious, the morality of charity bazaars, and the flaws of socialism.

How could Carroll, so careful an author in Alice, write a book so ill-organized and un-pruned? He explains in the preface that he had been collecting materials for many years-- clever ideas, satires, dialogues, strange inventions. He was involved in doctrinal controversies in the Church and political controversies at the University. And he wanted to put it all together into a novel.

Dodgson/Carroll’s own creativeness got him into trouble. He was a continuously inventive person, thinking up new machines and games, writing poems and stories, collecting drawers full of fragments. Many authors collect such material in their notebooks; F. Scott Fitzgerald’s notes became famous when they were published after his death. Dodgson/Carroll was an intellectual hoarder or pack-rat, and his treasury of scraps grew over the years to the point where two substantial volumes could contain them only clumsily. *

* The two volumes of Sylvie and Bruno are four times as long as Alice in Wonderland.

Downstream from Alice: the Oz books

In 1900, L. Frank Baum published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, to big national sales and critical admiration. Four years later, he repeated the success with The Land of Oz. The original Oz book was a one-shot deal and Baum did not plan for it to be a series. He saw the book as a springboard to his lifetime ambition for a theatrical career, by making The Wonderful Wizard of Oz into a musical. It took two years before he got a production, which played first in Chicago and intermittently on Broadway during 1903-04. The play was oriented to adults, dropping the witches and magic, shifting the plot to political struggles around the Wizard, and adding contemporary political parodies. But an outpouring of letters from children convinced Baum to keep the children’s book concept going, no doubt prodded by the relative failure of his other enterprises.

This would be the pattern throughout the remaining 20 years of his life; every time he wanted to quit and concentrate on something else, market pressures kept returning him to his one big source of audience appeal. Baum produced a total of 13 Oz books, and after he died in 1919, his publisher had other writers continue the series, bringing out a new Oz book every year through 1952. It was the archetypal sequel franchise. The question is, not just why the original Wizard of Oz was successful, but why it was perhaps the greatest sequel machine of all time.

The Land of Oz, as the subtitle says-- The Further Adventures of the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman -- featured the most popular characters in the original; the actors who played them in the stage production became famous. Neither the protagonist Dorothy, nor the Wizard, are what drive the sequels. The Wizard is gone at the end of the first volume, exposed as a mountebank who returns to Nebraska in his balloon; the protagonist in the new adventure is a boy named Tip. The generic features remain, of course: an alternative world which transforms features of the ordinary world; a naive child protagonist who has picaresque adventures; plot tension provided by evil adults (in this case Mombi, an old witch who is like a wicked stepmother to Tip at the beginning of the story); adventures always turning out happily because of the timely discovery of magic powers and the aid of new creatures brought to life (of which the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman are the archetypes).

In this first sequel, Tip constructs a pumpkin-head man and brings him to life by stealing Mombi’s magic powder; then brings a wooden saw-horse to life to carry them; then a flying machine cobbled together out of a pair of high-backed sofas, an elk’s head, and some decorative palm fronds for wings. This was very timely in 1904, the year after the Wright Brothers’ first flight in December 1903, although flying machines had been an inventor’s craze for the past decade. The common denominator of the method is to take found objects of everyday life (scarecrow, pumpkin/jack o’lantern, sawhorse, the household furnishings that make up the flying Gump) and bring them to life. Baum combines this with an adventure plot line, essentially a series of crises or cliff-hangers (in this book, literally, when the Gump crashes in a cliffside birds’ nest), from which the growing crew of adventurers escapes by another turn of magic creativity.

Baum (and his successor) would use this formula throughout the later books. For instance, in Ozma of Oz (1907), the child protagonist visits the land of the Wheelers, who are half-human/half bicycle.

The Oz stories have much less of the paradoxical, two-level dialogue by which Lewis Carroll constructs his successive episodes. Carroll’s humanized animals and nursery story creatures do not accompany Alice on her travels, but are largely one-episode appearances in which she has a nonsensical conversation. Baum’s dialogue is mostly about the problems the traveling crew are facing at each juncture, but there are occasional flashes of Alice-like devices. In one predicament, they find a secret compartment with three magic wishing pills, but its formula is to count to 17 by two’s. The characters discuss how this is impossible, since 17 is an odd number; until one of them suggests starting at 1, and going 3-5-7-etc.-until 17. Tip takes one of the pills, but it gives him such bad stomach pains that he wishes he hadn’t taken the pill; so now the three pills are back in the box. This leads to a discussion about whether Tip really could have had a pain, since he didn’t really take one of the three pills. This is essentially a riff on the time-reversal paradoxes in Through the Looking Glass.

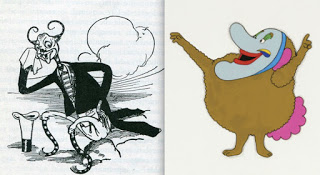

A new character, Mr. H.M. (Highly Magnified) Woggle-Bug, T. E. (Thoroughly Educated) is the precursor to the Yellow Submarine’s Jeremy Hilary Boob, Ph.D. (which Ringo pronounces, phud). Both begin by presenting their card. They are well-educated intellectuals, full of esoteric and pretentious language. The Woggle-Bug is also a version of the original Wizard of Oz, and continues the satire on education at the end of the first book, where the Wizard solves the Scarecrow’s request for a brain by giving him a university diploma. What makes the Woggle-Bug most memorable (in addition to the way he is drawn-- a bug walking upright on its hind legs, dressed in cutaway tailcoat, striped vest, and top hat-- an echo of the White Rabbit) is how he is created: a tiny bug whom a school teacher has magnified and projected onto a screen; when the teacher’s attention is distracted, the bug walks off the screen, in the size of a human child. There is more of this playing with scientific experiments in the Yellow Submarine.

The larger plot-tension of the story is driven by a revolution, carried out by an army of girls, led by General Jinjur. They are a feminist army, declaring that men have ruled things too long while women do all the work at home; and they succeed in overthrowing the King of Oz (who is now the Scarecrow, supported by an Army consisting of one old man with long whiskers and an unloaded gun). The girls are armed with knitting needles, plus their well-founded expectation that no one would hurt a girl. They proceed to carry out a revolution, which consists of prying out the jewels of the Emerald City so they can wear them, while the men now do all the housework. Baum is making literary capital out of current events; he was closely associated with his wife’s mother, a leader of the Women’s Suffrage movement. Although his parody of the movement is none too favorable, his books throughout often show girls doing men’s jobs. General Jinjur’s revolution is overthrown by another army of girls, led by Queen Glinda the Good Witch, this time carrying real weapons.

The book ends up with a discussion of who should have the throne of Oz. The Wizard had gone back to Omaha in his balloon; the previous ruler disappeared. They discover there was a descendent, a girl named Ozma, but the witch Mombi had transformed her into some other shape so she couldn’t be discovered. Eventually, after a trial of rival magic between Glinda and Mombi, the latter confesses that Ozma has been transformed into a boy: in fact it is Tip.

Tip at first is horrified to hear this, since he does not want to be transformed into a girl. His friends assert they will continue to like him just as much, and he undergoes the transformation into a beautiful princess with sparkling jewels (depicted on the last page of the book). This is a rather astounding ending, given that it was 100 years before the transgender movement became popular. It had no political significance; it was just a clever device for ending the book, and with a boffo effect, outdoing all the other magical transformations that moved the plot along. The book is innocently non-sexual; apparently the audience loved it, for the demand for Oz books accelerated. Ozma of Oz would soon have her own book, in 1907.*

* The formula is spelled out pretty clearly in the subtitle: Ozma of Oz Tells More About Dorothy and the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman, also about the New Characters-- the Hungry Tiger, the Nome King, Tiktok and the Yellow Hen.

L. Frank Baum’s failures: what made the difference?

Baum had been writing plays and musicals and acting in them ever since he was a child-- the same era of home entertainment as Lear and Dodgson with household poetry recitations. Baum was born in 1856, and grew up consuming the children’s literature of these predecessors. His father was a successful entrepreneur in many businesses, and Frank also had the entrepreneurial style from an early age; in his teens he ran a stamp collectors’ magazine; a stamp dealership; sold fireworks; in his 20s he published a trade journal for breeders of prize poultry. His father underwrote his theatre, and Frank wrote advertising for his aunt who was both an actress and founder of an Oratory School. None of his enterprises took off; and his father’s oil business went under. At age 32, Baum moved to a frontier town in the Dakota Territory (not yet a state), where he ran an unsuccessful store and edited a newspaper. Moving to Chicago, he became a newspaper reporter, and edited a magazine of ideas for advertising agencies, specializing on store window displays, and published a book about clothing dummies in 1900, the same year as The Wizard of Oz.

Baum’s first venture into children’s books came in 1897, with Mother Goose in Prose. Retelling meant elaborating the original rhymes into narrative and dialogue; in effect, this was what Lewis Carroll did when he constructed the culminating action of Alice in Wonderland from a few stanzas about the Knave of Hearts who stole the tarts from the Queen. Baum was 41 years old at the time of his first success, after a lifetime of eclectic projects. Following the groove, in 1899 Baum brought out Father Goose, consisting of nonsense poems in the Edward Lear/ Lewis Carroll tradition. It topped the sales charts for children’s books, so in 1900 Baum and his illustrator launched his own version of a trip to Wonderland, starting in Kansas and resembling the western United States.

Alice becomes Dorothy; the Red Queen becomes the Wicked Witch of the West with an army of flying monkeys instead of playing cards. The most innovative character, the Wizard of Oz, is Baum satirizing his own professional life of huckstering. Dorothy arrives in Oz via a tornado, receives magic shoes to protect her, recruits three clownish companions, and proceeds on a series of picaresque adventures. High points are the Emerald City itself, green and glittering with jewels; and the geography of Oz, divided into four kingdoms each with its own omnipresent color and reigning good or evil Witch. The geography would become a principle dimension for further sequels; although Baum never provides a map (as Tolkien did for his enchanted lands), the Oz alternative universe acquired a familiar shape for its readers, as each book added new places to its borders. For the first Oz book, Baum borrows a device from classic hero tales: an ordeal that Dorothy and her companions must undertake-- to steal the magic power of the Wicked Witch of the West-- before the Wizard will tell Dorothy the secret of how to return home to Kansas. After many adventures, she does; with a presumably final note that there’s no place like home.

The book again topped the best-seller list for children, but Baum did not sense what market niche he was in. He persisted in trying to produce plays. Tired of Oz, or not recognizing its appeal, he wrote a number of other children’s fantasy books: Dot and Tot of Merryland (already in 1901 on the heels of the Wizard of Oz success), Queen Zixi of Ix, Adventures of Santa Claus (another effort at a spin-off on the formula of his Father Goose), and others, none of which sold well. Sheer market demand for more about Oz-- above all its geography and tradition-- pulled him into sequels. The musicals he financed-- both follow-ups to his one big Wizard of Oz hit, and other ventures as a Broadway producer-- lost money. (One of the flops was meant to be a musical starring the Woggle-Bug.) In 1908, his traveling show simulating a trip to Oz combining short film clips, live actors, and his own Chattauqua-style lecture, almost bankrupted him. True enough, the period around 1908-1914 was when the film industry was shaping up, and it was unclear how short soundless films were going to develop; Baum was combining existing modes of entertainment he had grown up with, but which would be supplanted by movie theatre chains he had not foreseen.

In 1914 (when Baum was 58), he started his own film studio; but even its name-- The Oz Film Manufacturing Company-- did not make it successful and it folded after a few years. The early film industry appealed mainly to adults, with its dialogue boards and relatively slow-moving action. It would take the advent of talkies, background music, and animated cartoons in the late 1920s to create a sustainable children’s film market. By 1939, of course, The Wizard of Oz became an epoch-making film, using switches between black-and-white and color to highlight the transition between the ordinary world and the marvelous alternative universe; and being one of the first full-length features in garish Technicolor was a perfect match for the color-laden land of Oz. Already in 1906 Baum attempted to set up an Oz amusement park; this precursor to Disneyland (which opened 50 years later, in 1955) never got off the ground, hampered by his many failing business ventures. Baum was a promoter and entrepreneur in many areas; but having the concept was not enough to pull it off. Only in the Oz books, where his ideas could be quickly and inexpensively realized in print, and where collaboration involved only a favorite illustrator, could Baum make his skills pay off.

Altogether L. Frank Baum wrote 55 novels, hundreds of poems, and numerous film scripts. He had no shortage of inventive ideas. It takes more than inventiveness to create a beloved classic. The Oz books enterprise, if not Baum himself, recognized this; his publishers (who had acquired the royalty rights during one of Baum’s periodic financial crises) made sure that the winning formula kept being applied, for 30 years after his death.

Film Era Cross-over Sequels

The switch from books to films was no drastic change. From Alice onwards, successful cross-over novels had illustrations so that fantasy creatures did not have to be left to the imagination. The 1951 Alice eliminated the talkier episodes, verbal conundrums, and poem parodies and played up the most colourful scenes. All the classic fantasy films were the brightest and most vivid of their time. Film-making and sound-production technologies got better over time, one element in creating new effects within the genre. But new technologies succeed only in combination with the basic devices for constructing cross-over fantasy.

Song lyrics into film script: The Yellow Submarine

Immediately upstream from the 1968 film were the Beatles. Neither film script nor production was their doing; even their voices were those of professional actors. The Beatles’ input consisted of four new songs, plus some voiceless sound tracks by their studio music producer, George Martin, who was responsible for the innovative electronic effects of the Beatles’ sound. Otherwise the film writers chose existing Beatles hits, and scripted the film around the “We all live in a Yellow Submarine” song of 1966 and the nostalgic "Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band" (1967). The film is a sequel, an adaptation of what could be constructed from the Beatles’ music and image, and above all, from their lyrics.

In their generation, the Beatles were the most literary of pop song writers, and had the broadest range of musical knowledge. This was the era of transition from 45 rpm singles to LP albums with 6 or more songs per side. The Beatles’ breadth of musical styles came out gradually, as their immense popularity and two albums per year gave them opportunity to mix in new styles. *

* They were also one of the first groups to write their own songs and lyrics. Professional Tin Pan Alley song-writers since the record business developed in the early 1900s were rarely the performers, and the separation held up through most 1950s rock n’ roll. The Beatles began by adapting existing rock n’ roll songs to their electric instrument-playing quartet, but their popularity took off when they wrote their own material. This rapidly became the pattern for rock musicians.

Early Beatles hits had minimalist lyrics, the songs mainly carried by the all-electric-guitar sound, replacing the saxophones and horns of 1950s American rock n’ roll. American lyrics were mostly hyperbole or sheer hopped-up jitterbugging; (Little Richard: Gonna have some fun tonight, Everything’ll be alright, Gonna have some fun, Have some fun toni-i-i-i-ght [held through 5 beats]; Jerry Lee Lewis: Come on over baby, Whole lot a shakin’ going on [repeat, repeat...].

I Want to Hold Your Hand (1962), the Beatles’ first hit, is an upbeat screamer of teeny-bopper love; but Please Please Me (the same year) and Love Me Do (also 1962) have the flippant conciseness of Lennon and McCarthy’s lyrics. Their titles give a hint of verbal cleverness that straight-forward American songs lacked: A Hard Day’s Night (1964), Eight Days a Week (1964), The Night Before (1965), Got to Get You Into My Life (1966), Hello Goodbye (1967).*

* This is on display in Lennon’s two books of cynical nonsense stories, In His Own Write (1964) and A Spaniard in the Works (1965) -- British equivalent of the American expression, to throw a monkey wrench [spanner] in the machine.

Lennon and McCartney were finding a stream of material by casting an ironic eye on the daily lives of teens. I’m Looking Through You (1965), Ticket to Ride (1965), She Said She Said (1965), and You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away (1966) are songs about teenage complaints and break-ups, hardly original topics but treated with a irony and the bouncy music that makes them trademark Beatles songs.

They were also adding a serious vein: Poignant short stories are compressed into lyrics like She’s Leaving Home (1967):

Wednesday morning at five o’clock, as the day begins,

Silently closing her bedroom door,

Leaving the note that she hoped would say more.

She goes downstairs to the kitchen, clutching her handkerchief.

Quietly turning the back door key,

Stepping outside she is free.

Father snores as his wife gets into her dressing gown.

Picks up the letter that’s lying there.

Standing alone at the top of the stairs.

She cries and breaks down to her husband,

“Daddy, our baby’s gone!”

“Why would she treat us so thoughtlessly?

How could she do this to me?”

-- all this over the strumming chord changes and the band repeating softly in the background

We gave her most of our lives... Bye, bye..

Already in 1964 there was that great departure for rock music, Eleanor Rigby, where the jaunty bluesy music is played by a string quartet:

Eleanor Rigby,

Picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been,

Lives in a dream---

Waits at the window,

Wearing a face that she keeps in a jar by the door,

Who is it for?

All the lonely people, where do they all come from?

All the lonely people, where do they all belong?

Eleanor Rigby

Died in the church and was buried along with her name.

Nobody came.

Father McKenzie,

Wiping the dirt from his hands as he walks from the grave,

No one was saved.

All the lonely people...

This existentialist bleakness, echoing Samuel Beckett plays but relieved by the tenderness of the tone, is chosen for background music when the Yellow Submarine first arrives in Liverpool, a blip of colour across gray photographic stills of the industrial city. A basic ingredient of putting together the movie, surely.

Childhood fantasy now teeters on the portal to the alternative universe, half held back in the ordinary world. Downstream from Lewis Carroll, a riff on Mother Goose is in Cry Baby Cry (1968):

The King of Marigold was in the kitchen

Cooking breakfast for the Queen.

The Queen was in the parlour

Playing piano for the children of the King.

Cry, baby, cry, make your mother sigh,

She’s old enough to know better,

So cry baby cry.

The Duchess of Kirkaldy, always smiling

And arriving late for tea.

The Duke was having problems,

With a message at the local Bird and Bee.

Although it is not in the film, this song expresses the Beatles’ mentality at the time. Another echo of the nursery, from the mother’s point of view, is Lady Madonna (1968), sung above a piano boogie-woogie, with a Thirties dance band for the breaks:

Lady Madonna, children at your feet,

Wonder how you manage to make ends meet.

Who finds the money when you pay the rent?

Did you think that money was heaven sent?

Friday night arrives without a suitcase,

Sunday morning, creeping like a nun.

Monday’s child has learned to tie his bootlace.

See how they run----

Lady Madonna, lying on the bed,

Listen to the music playing in your head.

Tuesday afternoon is never-ending,

Wednesday morning papers didn’t come.

Thursday night your stockings needed mending,

See how they run---

(echoing the nursery rhyme, Three Blind Mice)

Such were the ingredients; now the movie:

Yellow Submarine is a trip to an alternative universe of sounds as well as visuals. It begins with classical music, played as orchestral background during the Blue Meanies’ attack on Pepperland, featuring a string quarter that gets bonked into grey cardboard silence. The Yellow Submarine makes its escape while we hear the title song played by a traditional brass band (sketching music history here, early jazz having come from syncopated marching bands). Reaching Liverpool, we are still in the classical string quartet of Eleanor Rigby. Not until we get inside the Beatles’ fabulous mansion-- outwardly a bleak-looking warehouse-- does full colour take over.

The opening sequence expands on the opening of the 1939 Wizard of Oz, where the scenes in Kansas are in black-and-white, and Dorothy lands in Oz in a blaze of Technicolor. Inside, contemporary pop music comes on only in snatches, as the Beatles marshal themselves to the rescue. It is more than 20 minutes into the film before, the Yellow Submarine under way, the Beatles’ up-beat sound takes over. And of course, when they reach Pepperland, what little plot is left consists of recovering their instruments and destroying the Blue Meanies’ spell simply by playing their irresistible music (“Nothing is Beatle-proof,” John says).

The Blue Meanies hate music, just as the older generation of musical taste attacked the new rock n’ roll music of the mid-1950s. (It emerged in the U.S. on independent radio stations, as the networks abandoned radio for TV; a favorite item of consumption in the rise of a modern youth culture during the push to keep working-class teenagers in high school instead of going to work; and the concomitant appearance of youth gangs (for whom the term “juvenile delinquents” was coined), who flaunted jive music and sometimes had their own singers.) The battle for rock n’ roll was finally won by the Beatles, who won over the older generation (not incidentally because they were white, clean-cut, clever and literate, and quoted older music-- in contrast to the black and hillbilly/ rural white singers of American rock n’ roll). The struggle of taste-generations is softened in the film: the Blue Meanies hate all music, even classical, although it is rock music that vanquishes them.

The Beatles stretch the formula for cross-over children’s fantasy, since they are not little girls, nor naive. John Lennon even remarks on similarities to their experience in Einstein’s relativity and Joyce’s Ulysses. The lack is remedied by adding the Nowhere Man, a satirical portrait of an Oxford intellectual, who knows everything but is inept in real life. The Boob becomes the most lovable character in the film, along with Ringo, who is always pulling levers and pushing the wrong buttons, creating the mini-crises that enliven the plot. Not having a naive protagonist eliminates the two-level humor and irony of the Alice novels, but an equivalent is in the new cartoon effects.

Yellow Submarine was a big shift from prior animated films, both visually and musically. The most ambitious full-length cartoon Fantasia (1940) featured Mickey Mouse characters accompanying a classical orchestra repertoire. Disney’s children’s films up through the 1950s-- including Alice-- have a sweet, syrupy orchestral background and feature songs that sound like Broadway musicals. These were explicitly children’s films, done at a time when youth music did not yet exist.

The Yellow Submarine was produced 15 years before desk-top computers, but a huge crew of 200 animation artists pioneered what would later become computer-animation effects. Sleeping Beauty (1959), the most lavishly and colorfully drawn of its predecessors, took 6 years to produce with a then unprecedented staff of artists; Yellow Submarine took 11 months. The sea the submarine travels through is made up of background stills, assembled out of collages of multi-colored strips, with fish-collages moving across the foreground.

The limited animation of the characters is made into a virtue. When the Beatles arrive in Nowhere Land and meet Jeremy Boob, they walk forward leaving a shadow-collage of flowers and fanciful psychedelic shapes behind them; and at the windup of the sequence, the film is played backwards so that the Beatles absorb their own shadow-trail.

Psychedelic art (initially in posters for San Francisco rock concerts) was a revival of Paris advertising posters like Mucha at the turn of the 20th century. Another ingredient in the Yellow Submarine is surrealist art of the 1920s and 30s. When Captain Fred first arrives at the Beatles’ mansion, he finds himself inside a vast hall of doors-- a reprise of Alice at the bottom of the rabbit hole. When a character enters a door, we see what happens in the vacant hall left behind:* strange objects scoot from one room to another, a circus strongman with barbells, an arm, an umbrella, a giant snail, Toulouse-Lautrec spinning a top with an elephant.

* This mini-sequence plays with a long-standing philosophical question: what does the world look like when no one is looking at it? John Lennon’s “It’s all in the mind” comment is George Berkeley’s idealist philosophy. Another philosophical sight-joke is Ringo’s car, which keeps changing the colors of its body and wheels when George asks him to identify it; the contemporary philosopher Strawson raised similar questions about the identity of objects: if a car has most or all of its parts replaced, is it still the same car?

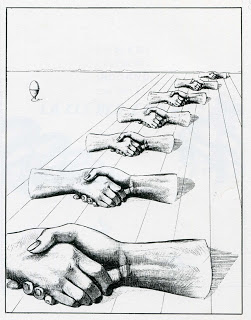

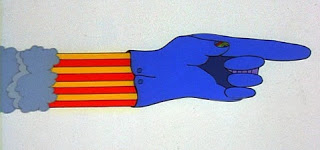

These are essentially surrealist images, especially Max Ernst’s collages made in the 1930s from 19th century magazine advertisements. We will see them again in the Sea of Monsters and in Pepperland, where the emblematic clasped hands of LOVE are right out of Max Ernst, and the guided missile-like glove is a sinister version of an old-fashioned advertising hand-pointer.**

** Surrealists assembled art from existing images or found objects, taking the collage technique of the cubists a step further. Surrealists rediscovered L. Frank Baum’s technique of creating an alternative universe by bringing everyday objects to life, except surrealists were aiming at a hyper-sophisticated audience of Paris intellectuals.

Surrealist art provides the model for the animated creatures of the under-sea voyage, such as brightly colored fish swimming with human arms.

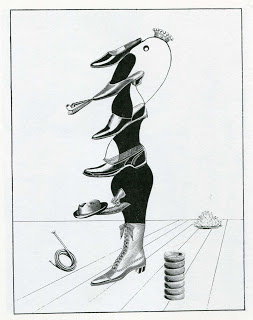

In the Sea of Monsters, the submarine gets into a stomping contest with a pair of Kinky Boot Beasts-- another Max Ernst conception:

Like Alice, the plunge into the alternative universe comes with repeated transformations of self. Clocks start going backwards and the Beatles shrink as they grow younger.

“What a curious feeling!” said Alice. “I must be shutting up like a telescope.” ... she waited a few minutes to see if she was going to shrink any further: she felt a little nervous about this; “for it might end, you know,” said Alice to herself, “in my going out altogether, like a candle. I wonder what I should be like then?” And she tried to fancy what the flame of a candle looks like after the candle is blown out, for she could not remember ever having seen such a thing.”

Captain Fred comments, "If we keep going backwards at this rate, we’ll disappear up our own existence." Managing to reverse the arms of the clock so that time speeds up, the Beatles find themselves with cascading beards visibly aging into “senile delinquents”. As usual, the Beatles apply their music-magic, singing about aging, a virtually unprecedented topic for anyone but themselves:

When I’m Sixty Four (1967), treats a topic that earlier love songs had rarely approached more closely than Gershwin's (1938) Our Love is Here to Stay “Not for a year, But forever and a day...”

When I get older, losing my hair,

Many years from now,

Will you still be sending me a valentine,

Birthday greetings, bottle of wine?

If I’d been out till quarter to three,

Would you lock the door?

Will you still need me, will you still feed me,

When I’m sixty-four?

This is used in the film as the Beatles pass through the Sea of Time, ending up with a sequence of images played at exactly one per second, introduced by the title board: “SIXTY-FOUR YEARS is 33,661,440 minutes, and ONE MINUTE is a long time”-- and the numbers count themselves on the screen in bright cartoony caricatures of 1, 2, 3 through 64 which shows two old people kissing. This is the phenomenology of experienced time vis-à-vis clock time in as visceral a demonstration as Bergson could wish. The hip audience could connect it with Timothy Leary and Baba Ram Dass on tripping out into the here-and-now.

Now we are in spacey-land, the humorous semi-meaningful nonsense of Alice and Oz mutated into visual-philosophical trips. The next scene is nothing but images of the Beatles’ heads against a black space, while we hear “Only a Northern Song” (newly written for the film by George Harrison):

If you’re listening to this song

You may think the chords are going wrong.

But they’re not,

He just wrote it like that.

When you’re listening late at night,

You may think the band are not quite right.

But they are,

They just play it like that.

It doesn’t really matter what chords I play,

What words I say,

Or time of day it is,

‘Cause it’s only a Northern Song.

If you think the harmony

Is a little dark and out of key.

You’re correct,

There’s nobody there.

Northern Songs was the company that copyrighted Beatles songs. This was in-group knowledge, but that is hardly the point. The music is electronically distorted, not just the chord changes but wavering organ strains and deliberately inserted static; meanwhile the screen shows images of the sound waves from an oscilloscope, bright flashes spanning the black space between the ears of the four Beatles’ heads; then the oscilloscope waves rotate sideways, in an early version of computer-assisted design, to create forms never seen on the screen before. (A similar technique-- slit-screen photography-- was seen the same year in the spacey climax of 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film that hip audiences liked to watch while on LSD.) George’s lyrics may sound weird but they tell us straightforwardly what the Beatles are doing at this phase in their musical career: trying new musical variants and verbal combinations to see what they sound like. This is Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll’s nonsense poetry, transferred into a new medium with vivid sensory dimensions, a literal cross-over of sight and sound.

The Sea of Monsters includes sight gags and melodrama, but is most notable for a further philosophical twist. Among the various monsters the most deadly is the Vacuum Monster (a combination of man, cat, and vacuum cleaner), who sucks up other creatures through his long tube-snout. After a chase, the Yellow Submarine itself is sucked in. End of film? No-- the Vacuum Monster, having sucked in all the other monsters, breaks frame by grabbing a corner of the picture and sucking the entire visual screen into itself. Alone in empty space, he sees his own tail wagging, turns and sucks it in-- thereby placing his whole body inside himself. Whereupon, pop!-- the Yellow Submarine is released back into reality. Mathematical logician Lewis Carroll would have appreciated the visual play on the theory of sets containing sets (here, the equivalent of putting a computer file into itself).

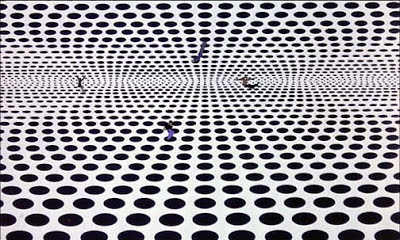

More spaciness. The Beatles reach the Head Lands, consisting of human heads with the brain cavity exposed, showing their thoughts in bright-colored images. John, who thinks about sex, then sings Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, a head trip of LSD-like images melting into each other. Then the Sea of Holes, a surrealist design in black-and-white, with computer-design-like effects of shifting and self-mirroring planes of perspective, the whole thing vibrating along with the crescendoing sound, until, pop! again-- they have precipitated out of this metaphysical warp and find themselves on their feet in Pepperland.

The battle with the Blue Meanies brings the level down a notch. Since nothing can resist the Beatles, they can’t lose the battle. A little suspense is provided by sneaking into the bandshell to find musical instruments. In a scene reminiscent of the 1939 Wizard of Oz, the Beatles join a marching file of enemy soldiers (in this case, Apple Bonkers) by disguising themselves as one of them. The battle is mostly notable for its political resonance. The anti-war movement against the Vietnam War was at its height; the Blue Meanies have Nazi overtones, but their weapons are clown-shaped nuclear bombs. The homing-missile glove is virtually an American flag, red-white-and-blue modified into a sleeve of red-and-yellow stripes.

An anti-war movement winning a violent battle is self-contradictory (although that is a real-life conundrum in the demonstrations and riots of 1967-68), but the film has the perfect answer. “All You Need is Love” is the slogan, sung during this part of the film, plus the power of music: Blue Meanies’ machine guns start shooting flowers, and the chief Blue Meanie ends up with a rose on his nose. Flower power, all right, unmistakably a version of demonstrations at the Pentagon and elsewhere in 1967 when hippie girls put flowers in the barrels of soldiers’ guns. But too much seriousness is poison for a cross-over fantasy, and it is kept low key as the film ends in a psychedelic poster-tableau of former enemies entwined in reconciliation.

Recombining Classics, Japanese-style

Hayao Miyazaki rode the Japanese wave of world-popular manga comic books and anime film in the 1980s. His apprenticeship, starting in the 1960s, was in cheap-labor Japanese animation for American children’s TV cartoons, moving on to publish manga such as a comic book Puss in Boots. (His early path is like L. Frank Baum re-doing Mother Goose and Santa Claus in a new medium.) After 20 years of absorbing Western popular culture and the rapidly improving Japanese film techniques, Miyazaki began turning his manga into full-length feature anime. After another 20 years of weaving between sentimental children’s films, retro-European historical adventures and science-fiction settings, always visually dazzling, Miyazaki at age 60 produced a fairly explicit sequel to Alice in Wonderland in Japanese guise.

The alternative world in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away is a pre-modern bathhouse, where the gods of ancient Japan come to relax. It is luxurious on a scale reminiscent of the Yoshiwara pleasure district of Edo, with a certain amount of historical anachronisms such as a boiler room, train tracks, and telephone. Most of all it is a trip to the past-- for the audience; for its protagonist, a ten-year-old girl of the 1990s, it is sudden immersion in old-fashioned manners. She starts out as a spoiled, bored, mopey, impolite child in sloppy-casual Western clothes, indulged by her parents; to survive, she must perform old-fashioned etiquette and obedience to superiors.

Driving the plot tension, Chihiro’s parents have been transformed into pigs (Circe-like) while over-eating in an abandoned theme park inhabited by ghosts. She can only rescue them by getting a job at the bathhouse, where all the creatures are hostile to humans. At first everything is frightening. The guests look like monsters, strange cloak-shaped blobs with ancient Japanese masks for faces; some look like animals-- giant chicks, an enormous walking walrus that shares an elevator with Chihiro; the kitchen staff and male attendants are frogs and fishes standing upright (a combination of Alice and surrealist images). The waitresses are women in geisha robes, presumably ghosts, since they object to Chihiro’s human smell. Chihiro’s place is assigned among the cleaning-maids, a rough-talking bunch. She is given the hardest tasks, like scrubbing floors with a wet rag, and finds she can’t keep up with other maids scurrying in tandem across the floor.

In the magic-helper tradition, she acquires friends. At the outset, a handsome teenage boy, Haku, tells her what she must do to rescue her parents, and gives her a pill that stops her from becoming transparent like a ghost. She seeks a job from the boiler-room engineer, an old man with spider-like multiple arms that stretch like rubber to reach anything in the room; he is gruff at first but eventually takes her side after she has shown she can work. She is assigned to one of the cleaning-maids, who treats her with slangy working-class brusqueness, but shows her the ropes on the most onerous tasks, cleaning out a huge, filthy bathtub full of slime. The ordeals on her picaresque path are less the conversational conundrums of Alice or the life-threatening witches and monsters of Oz and Yellow Submarine, but the grubbiest aspects of ordinary working life.

The villain of the story is Yubaba, the old crone who owns the bathhouse, a witch who transforms herself into a crow to fly off during the day when the bathhouse is asleep (vampire theme). Yubaba makes Chihiro sign a contract of utter servitude, under the threat of being transformed into a pig and served up in the kitchen. Yubaba’s chief magic power is the ability to take away people’s names. In one of the spaciest scenes of the film, she sweeps her hand over Chihiro’s signature-- written as a column of Japanese characters-- leaving only a single syllable, so that she is now called Sen. Later Haku explains that if you forget your real name, you are totally in the witch’s power. Haku himself does not know his real name, and is under contract to Yubaba as an assistant with some magic powers. At the conclusion of the story, Chihiro/Sen finds Haku’s real name and releases him from the spell.

Yubaba is the Wicked Witch of Oz and the fairy tales, and visiting her is frightening at first. But whenever she is about to do something horrible to Sen, she is distracted by her crying baby. This baby is a giant, who looks like a sumo wrestler, inhabits a luxurious nursery, and is even more spoiled that Chihiro was by her parents. The baby is completely self-centered and demanding, and not only wails but is capable of destroying his surroundings. (These scenes look like a outgrowth of the Alice episode with the Duchess and crying baby who turns into a pig.) Yubaba shows another side, the ultra-indulgent grandmother. This is a psychologically more realistic way of solving a major problem of fantasy adventure-- the evil character must be powerful, but must have some weakness so that the hero can escape its dangers.

This is Miyazaki’s new twist: making the fantasy world psychologically real, and thereby producing less violent solutions than most action-adventure (or pre-modern fairy tales). The action of Spirited Away is thus much less violent than his other films like Princess Mononoke or Porco Rosso.

Sen gets through each episode by making friends out of unpropitious starts. In the boiler room, the furnace is fed by a crew of insect-like creatures who carry coal lumps bigger than themselves; when one of them falls down, squashed by its load, she manages to haul it to the furnace herself. This makes the rest of the coal-carriers all fall down and pretend to be squashed, leaving the work to Sen. They are driven back to work by the engineer, who threatens to magically turn them back into soot; but in future episodes they become her helpers.

In her work as cleaning-maid, Sen is thrown into the middle of two successive crises that threaten the bathhouse. A huge shapeless guest, dripping brown slime, wallows its way into the bathhouse and fouls its halls. It is a stink-spirit, and all the attendants hold their noses and fruitlessly try to keep it out. Sen is given the job of bathing it in a huge tub. Under the bathwater she manages to find a thorn stuck in the monster’s side; then the entire team of bathhouse workers, directed by Yubaba as cheer-leader, pull on a rope and finally extricate the contents of the bloated monster: a huge accumulation of trash and debris found at the bottom of a river. The stink-spirit transforms into a beautiful silver dragon, writhes dazzlingly making dragon-shapes in the air, and zooms out of the bathhouse, having left Sen a magic pill as a reward. This would be more familiar in East-Asian mythology, where dragons are supposed to be water-spirits, who manifest themselves as rivers and clouds. The ecological pollution theme is one of Miyazaki’s favorites, used in his previous films (above all Nausicaä, 1984), here combined with traditional dragon lore. Since Sen has already seen that Haku, when he flies off on mysterious errands, also takes a dragon form, there is a hint of what we are going to find out about Haku.

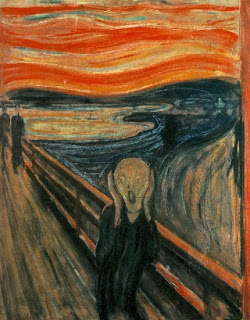

The second crisis revolves around a character called No-Face. This is a tall cloaked humanoid, all black except for a black-and-white mask face frozen in a sorrowful expression. When we first see No-Face, he is alone of the bridge outside the bathhouse, in a pose reminiscent of Munch’s The Scream.

As a spirit of sadness, he is banned from admittance. Sen takes pity on him and lets him in through a sliding screen. No-Face is the ultimate geek; he holds out his hand pathetically and can make no conversation other than feeble grunts. But he has magic powers; when the frog-official refuses to let Sen have the token needed to order scented water from the boiler-room, No-Face turns invisible and steals a handful of them for her. This provides a bit a magic-induced help that gets her started on cleaning the filthy tub, and solving the stink-spirit crisis.

Once inside the bathhouse, No-Face uses his magic to make himself popular: he creates gold nuggets for the attendants, who rush eagerly to feed him delicacies. This turns into a reprise of the opening scene where Chihiro’s parents cram themselves with goodies and turn into pigs. Now No-Face develops a huge mouth-- not in his face mask but in his belly (like the Snapping Turks in Yellow Submarine); he grows bloated with food, and eats any of the attendants whose service is not abject enough. He has also acquired a voice, a bullying and demanding one-- except when he talks to Sen, reverting to his halting pathetic grunts. No-Face has now become gigantic and is making more or less the same mess in the bathhouse as the stink-spirit; Yubaba and the others urgently call for Sen to help again. He offers Sen piles of gold, but she refuses. As a last resort, she gives No-Face part of the magic pill she had gotten from the stink-spirit-- she was saving it to rescue her parents, but this seems more urgent. Can’t Buy Me Love is the theme here; No-Face shrinks back down to his original form and leaves the bathhouse in peace, even regurgitating the frog/people he has swallowed.

The plot starts to tie up. Haku has returned in his dragon-shape, injured and bleeding, from some mysterious struggle; and she rushes to rescue him. Sen, seeking for Haku in Yubaba’s penthouse apartment, is caught by the baby who threatens to break her apart if she won’t play with him; Yubaba appears, but turns out to be another witch, Yubaba’s identical sister and rival Zeniba, who transforms the baby into a tiny mouse (who henceforward accompanies Sen), while leaving a fake baby in the nursery. Sen goes on a ghostly train-ride to Zeniba’s house, where she expects to make amends for Haku’s magic thefts; No-Face pathetically follows her, and she uses up her magical tickets to get him on the train. It is plain everyday life in early 20th century Japan, with a late 20th century girl sitting beside her sad tag-along friend. At Zeniba’s hut (a Grimm fairy-tale cottage), her apology is accepted, and she learns that the spell on Haku has already been lifted-- Sen’s love triumphs over magic (All You Need is Love). As she flies back on the Haku-dragon, she recognizes him as a river she fell into as a child, and tells him his river name. He transforms back into a boy, and they fall marvelously through a beautiful blue sky, hand in hand, to the bathhouse. No-Face even gets a home with Zeniba.

The film is about what it is like to be Japanese: all-out, high-effort but meticulous work; repetitive politeness-- bowing, chanting out welcomes, ritually apologizing for failures. (We also see the backstage, beneath the hierarchy, where workers among themselves are abrupt rather than polite.) Above all, dedication to the work-team, all efforts together for the common task. By the end of the film, Sen is popular with everyone. The bathhouse staff cheers her as Yubaba puts her through a last ordeal to save her parents from being slaughtered as pigs. In the end, the only bad guy is Yubaba, but Sen calls her Granny. It is a film of redemption, like Yellow Submarine, except there it only applies to the Blue Meanies-- under the power of the Beatles’ music, and not too convincingly.

Spirited Away, like Yellow Submarine, is a nostalgia trip: to the pre-war period, with deeper roots in Japan’s mythological past. (Pepperland, before the Meanie conquest, is Edwardian England, depicted idyllically in graceful, stylishly dressed cut-outs.) By the 1990s, Japan was not only the technological marvel of the global world, but losing its social forms to American-style casualness. No wonder Sen’s self-transformation and rediscovery of Japan made it the highest-grossing Japanese film of all time.

Spirited Away builds on all its predecessors. Sen falls down a long rickety flight of stairs to the boiler room, a more frightening version of down the rabbit hole; she walks through interludes with the cartoon-beautiful Haku in brilliant flower fields reminiscent of the 1951 Alice. On a deeper level, both No-Face (who might well be called No-Name), and the central metaphysical magic of bondage by being deprived of one’s true name, are sophisticated spin-offs of Lewis Carroll’s playing with the logical meaning of names, and the murkiness of passing through the No Name Woods.