The Mona Lisa is considered the world’s most famous painting, chiefly because of its mysterious smile. What is so mysterious about it? Art critics have projected all sorts of interpretations onto it, and these are endless. There is a more objective way to analyze the Mona Lisa smile, using the social psychology (or micro-sociology) of facial expressions.

As the psychologist Paul Ekman has found, analyzing emotions in photos all over the world, emotions are shown on three zones of the face: the mouth and lower face; the eyes; and the forehead. Our folk knowledge about emotions concerns only the mouth: the smiley face with lips curled up, the frowning face with lips turned down. These intuitions also make possible fake expressions. The mouth is the easiest part of the face to control. You can easily turn up the corners of your mouth, and this is what we do on social occasions where the expected thing is happiness or geniality. Arlie Hochschild, in The Managed Heart, calls this emotion work. In the contemporary fashion of political campaigning, politicians are required to be professional producers of fake smiles.

The muscles around the eyes and eyelids are much more difficult to control, and along with the forehead these are usually outside one’s conscious awareness. So a fake smile—or any other fake emotional expression—is easy for viewers to catch, because we are unconsciously attuned to the entire emotional signal all over the face. One reason we like photos of small children is that they haven’t yet learned how to fake emotional expressions.

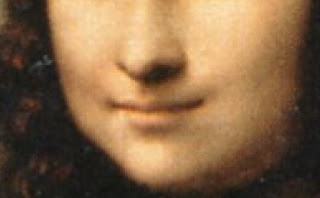

If we examine the Mona Lisa face, zone by zone, the reason for its mysteriousness becomes clear: there are different emotions expressed in different facial zones.

Her mouth, as everyone has noticed, has a slight smile.

Her eyes are a little sad.

Her forehead is blank and unexpressive.

We will see further peculiarities as we examine each in detail.

Mouth and lower face.

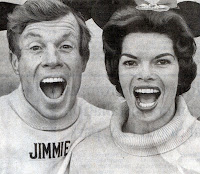

Smiles come in different degrees. As Ekman shows, stronger smiles—stronger happiness—pull the corners of the mouth further back (from the front of the face). Corners of the mouth may tilt up but they don’t have to; very strong smiles, which pull the mouth open and expose the teeth, often have the line of the upper lip more or less horizontal. What makes the smiley mouth is more the rounded-bow shape of the lower lip, and especially the wrinkle (naso-labial fold) that runs from the corners of the nose diagonally down to the beyond the corners of the lips. In very strong smiles, these triangle-looking folds become deeper, and are matched by a flipped-over triangle of skin folds from the chin to the outer corners of the lips, giving the lower face a diamond-shaped look.

Compare the Mona Lisa. This is a pretty pallid smile. Yes, she does turn up the lip corners a bit, but this is more of a conventional sign than what we see in a real smile. More importantly, there are no naso-labial folds running downward from her nose, nor any mirroring triangle up from the chin. Real smiles raise the cheeks (as we will see in a moment, this affects the eyes in a smile), but Mona Lisa hardly has any cheek features at all.

Eyes and eyelids.

Smiles, especially stronger smiles, make wrinkles below the eyes, more or less horizontal, slightly curved across the bottom of the eye socket (deeper wrinkles the more the cheeks are raised). This has the effect of narrowing the slit of the eyes, as the lower eyelid is raised. This is a tell-tale detail, since narrowing eyes can also happen in other emotions; in happiness, the lower eyelid may be puffed-out looking but not tense. (By contrast, angry eyes have very hard-clenched muscles around them; fearful eyes are wide-open and staring; sad eyes we are coming to). For the happy face, all these muscle movements cause crows-feet wrinkles to spread out from the corners of the eyes.

Mona Lisa’s eyes? The lower lids do look a little puffy, but there are no wrinkles below them; her cheeks if anything are flaccid. And no crows-feet.

Sad eyes.

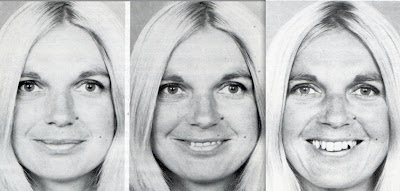

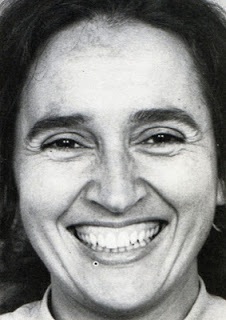

Sad eyes are passive. The lower eyelid is weak, and there is no horizontal wrinkle below it, since the cheek is not pushing up. Whereas in a smile the upper eyelid is open, so the eyes brightly look out, the sad upper eyelid droops a bit. Even more noticeable is the brow, which tends to collapse and sag downwards; this makes the skin of the upper eye socket droop almost like a veil slanting over the outer corner of the eyes. This is particularly noticeable in the picture of the Middle-Eastern woman below right; next to it is a photo of a woman at her lover’s funeral. The photo on upper left is a composite, with sad eyes at the top, and neutral lower face.

Mona Lisa’s eyes.

They are not brightly exposed and wide-open as in the happiness photos above, where the upper eye-lid is generally narrow as can be. Mona Lisa’s upper eyelids are partly closed, so are her lower lids; and the skin at the outer edges of her eye sockets droops a bit. These are sad eyes, although only mildly so.

Mona Lisa is a combination of sad eyes and a slight smile, but the way she is painted makes her even more mysterious. As already noted, she lacks the naso-labial folds and chin folds characteristics of happy smiles. Leonardo da Vinci did very little with the cheeks, but concentrated a great deal on the corners of the lips and eyes. This was his famous sfumato technique—a smoky look producing deliberate ambiguity. This also has the effect of obscuring just the places where important clues to genuine smiles are found; there are no crows-feet around her eyes, but then there are no expressive wrinkles in this painted skin anywhere.

Was this the actual expression Lisa Gherardini, La Gioconda, had on her face when Leonardo painted her? Probably not. Leonardo worked over all his paintings a long time; the Mona Lisa took him four years, and was still unfinished in his estimation. He kept experimenting with the portrait, quite likely upon just these features. The idea that Leonardo was trying to portray a specially mysterious lady was a favorite with romanticist 19th century art critics, as was the very unlikely idea that he was having an affair with her (he was apparently a homosexual, once charged with sodomy, and was never known to have a relationship with a woman). He was an artist in an era when artists were rivals over the super-star status of their time, and technical innovations made for fame. What we are viewing is less a real emotional expression at a moment in time, as a virtuouso experiment at the frontier of what could be pictured.

No eyebrows.

Another reason the Mona Lisa seems strange to us is that she has no eyebrows. For many emotions, the brows are important points of expression; as we have seen, somewhat subtly in sadness; in happiness, mainly by contrast with other emotions—unmoved eyebrows are generally part of the happy face, unless it is really over the top:

For anger, the position of the eyebrows is the strongest clue—the vertical lines between them as the facial muscles clench make even a stripped-bare cartoon emblem of anger.

So eyebrow-less Mona Lisa gives us less clues than usual to emotions; all we see are the bare ridges of her upper eye sockets through the haze of Leonardo’s sfumato, making even the sad expression less clear to us. There was nothing intentional about this; in the late 15th century shaved eyebrows were a fashion for European ladies, as we see from the Fouquet madonna (painted 1452) and the Piero della Francesca portrait (1465; the Mona Lisa was painted 1503-6).

This may be one reason why the Mona Lisa was not particularly well known in its day, nor was it considered mysterious, nor was there much comment on her smile. Leonardo da Vinci was famous but less so than his contemporaries Michelangelo and Raphael, and his most celebrated painting was The Last Supper. The Mona Lisa was a minor work until the 1850s-60s in France, and the 1870s in England, when it became the object of gushy writings by ultra-aesthete art critics, led by Théophile Gautier and Walter Pater. (The history of how this happened is told by Donald Sassoon, 2001.) Mona Lisa and her smile became mysterious, in fact the mysterious Feminine, an Eternal Spirit with all the Capital Letters. And not just the benevolent Earth Mother but a Cleopatra-Jezebel-Salomé temptress. This sounds like fantasies of mid-Victorian males—perhaps understandable in an era when women wore bustles and men hardly ever saw much more than their faces. As Sassoon notes, women were always much less taken with Mona Lisa than were men.

Is there any truth in the interpretation, that Mona Lisa was a subtly flirtatious sexpot? Again we can call on some objective evidence, how erotic emotion is expressed on the face.

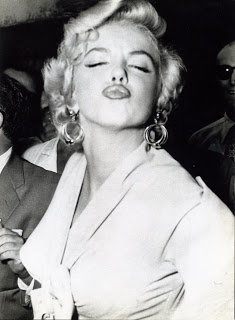

Sexual turn-on, at least for female faces, has a standard look (as can be seen by thousands of examples on the web): eyes closed or nearly so, mouth fallen open. The woman’s face is otherwise slack, no fold lines like other emotions; it may be happiness but the expressions are quite distinct.

Marilyn Monroe made the eyes-half-closed expression virtually her trademark. The sex idol of a less explicit era than today was also a great actress in her line.

Mona Lisa? If there is any sex in her face, only a repressed Victorian could see it.

So this is micro-sociology?

The purpose of micro-sociology is not to be an art critic. I only make the venture because so many popular interpretations of the Mona Lisa blunder into social psychology. But reading the expressions on photos is good training for other pursuits. Paul Ekman holds that knowledge of the facial and bodily expressions of emotions is a practical skill in everyday life, giving some applications in his book Telling Lies. And it is not just a matter of looking for deceptions. We would be better at dealing with other people if we paid more attention to reading their emotional expressions—not to call them on it, but so that we can see better what they are feeling. Persons in abusive relationships—especially the abuser—could use training in recognizing how their own emotional expressions are affecting their victims; and greater such sensitivity could head off violent escalations.

Facial expressions, like all emotions, are not just individual psychology but micro-sociology, because these are signs people send to each other. The age we live in, when images from real-life situations are readily available in photos and videos, has opened a new research tool. I have used it (in Violence: A Micro-sociological Theory) to show that at the moment of face-to-face violence, expressions of anger on the part of the attacker turn into tension and fear; and this discovery leads to a new theory of what makes violence happen, or not. On the positive side, micro-interactions that build mutual attunement among persons’ emotions are the key to group solidarity, and their lack is what produces indifference or antipathy. And we can read the emotions—a lot more plainly than the smile on Mona Lisa’s face.

References

Ekman, Paul. 1992. Telling Lies. Clues to Deceit in the Marketplace, Politics, and Marriage. NY: Norton.

Ekman, Paul, and Wallace V. Friesen, 1984. Unmasking the Face. Prentice-Hall.

Hochschild, Arlie. 1983. The Managed Heart. University of California Press.

Sassoon, Donald. 2001. Mona Lisa. The History of the World’s Most Famous Painting. London: Harper-Collins.