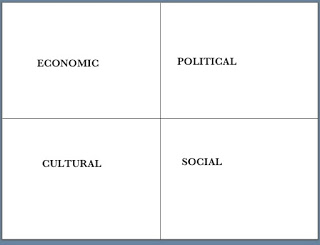

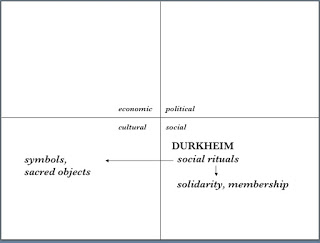

Everything in the human world has four aspects. They are easy to remember by putting them in four boxes:

The ECONOMIC box: This is a short-hand for the ways in which things are material, practical, or economic.

The POLITICAL box: Again a short-hand, for everything that involves power and conflict.

The SOCIAL box: the ways that people interact with each other, especially their emotions, rituals, and networks.

The CULTURAL box: people’s ideas and ideals about what they are doing.

Everything human has these four requisites.

If one or more is missing, the thing will fail.

Success requires all four in the right amounts. What are the right amounts? We shall see.

Analyze anything: some examples

The four boxes can be applied to anything.

Using the four-box scheme is like playing a game of tic-tac-toe or Sudoku.

But it is completely serious: a way to analyze anything that people are concerned about, from high politics to low entertainment.

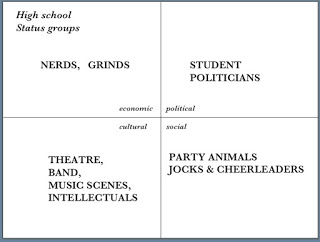

To show what you can do with it, consider the kinds of kids that everyone who has gone to an American high school knows about.

Politics has the same sub-divisions:

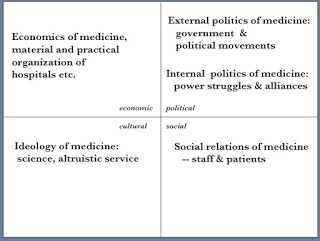

Now to put the 4 REQS to work. Filling in the four boxes for any activity shows what it needs for success and where are its dangers of failing.

Success and failure in medicine

The CULTURE box:

The ideals of medicine are to provide health and cure sickness. Medical professionals swear to uphold ideals of service and altruism. The culture of medicine includes doctrines about what causes illness and the scientific methods for dealing with it. This is the textbook definition of medicine.

How large does the ideology of medicine loom in the experience of a patient, or a medical doctor, nurse, or hospital employee? How important is for whether medicine succeeds or fails?

The ECONOMICS OF MEDICINE box:

The material and practical aspect of medicine starts from the fact that human bodies are handled by medical workers. A hospital is a lot like a factory. As in an assembly line, patients are interviewed, tested for body signs, have specimens drawn, sent to labs, seen by various specialists, have medicines hooked up or ingested, and are subjected to various body-intrusive procedures. In the mean time they are wheeled around from one place to another, moved into rooms when available, parked in hallways, and sometimes fed and cleaned. The more bodies there are moving through the medical factory, the more the fate of any one patient is affected by the sheer quantity of things in the assembly line.

Even the minor experience of how long you wait between the time you show up for your appointment and the time you actually see a doctor is determined by how many patients are scheduled and how long each one takes. The doctor may in fact be quite personable and try to treat each patient as an individual; but this has the effect that patients later in the queue end up waiting even longer. The large-scale bureaucratic side of the organization runs against the ideology of caring, so that many patients’ experience of a hospital visit is about as people-friendly as a Kafka novel.

Where patients undergo more extensive hospital procedures, one’s body rolling around on the gurney is not very different from an automobile part in a car factory, except that in factories the supply parts can’t complain about where they are stored; and hospitals can’t use the just-in-time delivery systems that factories use for off-site storage.

In short, the human experience of being in a hospital comes from being treated like a part in a not very efficient factory assembly line-- inefficient because humans are more unpredictable, especially in how long they will take to respond to treatments. The result is a lot of unaccountable waiting around.

Notice the contrast: the ideology of scientific/altruistic medicine describes it as its best; one of the things it omits is what the experience of being one of the bodies moved around in a hospital is actually like.

There is also the economics of medicine in the narrower sense: the costs of medical care, billing and insurance systems, doctors’ payments, administrative and staff costs, the hospital plant.

Many of these run in vicious feedback loops. Insurance companies’ efforts to keep costs down leads to an accelerating back-and-forth between hospital staffs and insurers disputing payments, with a good deal of fanciful accounting on both sides. It exemplifies the sociological process of escalation and counter-escalation of conflict. The result of this administrative warfare is that both sides expand their billing staffs, making administrative costs endlessly rise.

Another vicious feedback loop comes from the scientific culture of medicine:

scientific discoveries lead to new and improved treatments, especially with the expensive diagnostic equipment of recent decades (CAT scans, MRIs, etc.); the standard of treatment constantly rises and new levels of expense become normalised, putting more pressure on hospital administrators to add equipment and simultaneously to find creative ways to pass the cost along to someone else.

Here again the ideology of medicine runs against the economics of medicine. In the perfect world of economists, patients would be informed consumers who could compare prices and the values they get from various treatments and make their own decisions. In the real world of medical practice, patients are rarely informed of such things; typically the hospital or clinic takes the patient’s arrival at the door as an agreement to pay for whatever treatment the professionals decide to give, at whatever price they want to charge. The ideology of caring for patients does not extend to caring for them financially, nor paying attention to what medical costs can do to their lives.

The POLITICS OF MEDICINE divides into an external and an internal aspect. External politics involves government policies and debates, and political movements for and against particular ways of legislating about medicine. The ideological stridency reached by such debates today is obvious. Since the politics box includes any kind of conflict, it also includes law suits over medical malpractice, damages, and religious and cultural claims: all of which add to the economic and organizational burdens of medical professionals.

The internal politics of medicine is more local; it consists in alliances and power struggles over who runs a hospital; relations between outside doctors or privately owned clinics and hospitals they staff; and the financial politics of hospital chains, take-overs, and the usual maneuvers of the corporate world. Here the link between the pure ideology of medicine as altrustic service and realities of medical politics becomes so remote as to have virtually nothing to do with each other.

Finally, the SOCIAL RELATIONS OF MEDICINE:

How do people interact with each other? Patients and staff may try to keep up a pleasant, humane relationship; but the bureaucratic factory setting of medical organization makes it likely that most interactions are faked. Talking with a doctor or nurse is the Goffmanian front-stage, since the organizational and economic realities that the patient is caught up in are rarely even acknowledged. Since patients have so little power in the system, they try to put up a hopeful front, fearing that protest will only leave them more neglected in the bureaucratic queue. The ideology of the helpful, altruistic medical staff and the grateful patient is constantly strained. Most of their interactions would be considered mediocre Interaction Rituals, producing little real solidarity.

From the point of view of the bureaucratic organization, it doesn’t matter what the patients feel, since they are just the raw material running through the machinery.

Hospitals and clinics have developed a long-standing culture over the years of how to keep patients superficially quiescent; it used to be called “bedside manner” although now it includes advertising campaigns and manipulating the decor of waiting rooms. Strictly as an organization (i.e. the economics box), medicine doesn’t depend on solidarity with patients.

Lack of solidarity is more of a threat to relationships within the staff. The biggest problem tends to be the behavior of the most powerful professionals, the medical doctors. As a strong profession, they are well-networked among themselves; they can control each other’s careers by referrals, partnerships, and by word-of-mouth reputation. These advantages also are useful for economic interests as well, whether steering patients to expensive procedures from private groups of practitioners, or manipulating billing practices. Observational studies of hospitals show doctors who chase gurneys down the hall, briefly asking the patient how they are doing, then billing it as a full-scale consultation for the insurance coverage.

These kinds of practices undermine solidarity in the hospital work force as a whole.

How then do we rate medical success or failure?

The four boxes have quite different criteria. From the economic angle, success of a hospital or a medical practice is how much money it makes; failure would be medical bankruptcy. From the political angle, success would be a favourable political environment; failure would be a political swing that crushes the existing medical elite. Most of reality is in the middle ground of seemingly endless political contention. From the social angle, the criterion would be patient satisfaction; empirically this seems to be in the mediocre range.

Finally, there is the lofty ideal of health and altruistic service. This altruistic side of this seems badly compromised; what about health? The problem here is that it is a moving standard. Some diseases have declined; focus on other diseases has risen in their place. Objectively there is now more scrutiny of medical error (not unrelated to lawsuits over medical malpractice). Medicine as a whole has been successful in keeping people alive longer; it also keeps people under medical treatment longer, not necessarily making them healthier but living more years when they aren’t healthy.

It has often been cited that any individual will charge up more in medical costs in the last 6 months before dying than in the rest of their life. It is the same pattern with automobile repairs: an old car becomes progressively more expensive to maintain, until the owner finally decides to get rid of it. These are material realities; the political, social, and ideological aspects get piled on top and obscure the reality.

Can’t the success of medicine be measured objectively, by rating systems? Certainly one sees billboards in every city across America touting how highly rated a particular local hospital is.

Compared to what? and by what standard?

The naive way to read a rating system is just to accept the numbers.

The more intelligent way-- which takes more work-- is to look at how the rating was done. By opinion polling among doctors or hospital administrators? This relies on their gossip network. By objective measures: OK, which ones? do they measure how satisfied patients are, how favorable their medical outcomes, how serious their conditions were? The most common objective measure is of the extremes of failure-- mortality, infection rates, and complications from medical procedures. This is still only a small part of the picture.

The overarching problem is there are four dimensions to the medical system; and they are all unavoidable. Setting up a rating system for success or failure is itself a matter of politics, making choices over what to pay attention to and what to ignore. We are a long way from getting a reliable rating system that tells you which hospitals give you the best treatment at the best price, with the most pleasant human interactions.

Looking at the total picture for all four boxes, it appears that medical systems rarely fail completely, but the different components undermine each other so much that they rarely work at a high rate of success. Marshall Meyer and Lynn Zucker referred to these kinds of organizations as “permanently failing organizations.”

How can they go on failing, instead of going out of business and being replaced by more efficient organizations, as economic theory on its most abstract level would imagine? In part because medicine is in such high demand; even permanently failing organizations are better than none at all.

The best practical advance that sociology can offer is to pull back from the macro level where the four boxes clash, and focus on the social interaction box. Here are two important findings by medical sociologists such as Charles Bosk: First, the strongest predictor of medical failure is whether the patient feels the doctor doesn’t like him or her. In other words: a genuinely successful interaction ritual between doctor and patient is the best way to ensure the treatment will be successful. If there are bad vibes, find another doctor.

Second, medical error is much lower in Japanese hospitals than in American ones: Why? because in Japan it is customary for a close relative to always be present in the patient’s room. Someone who cares personally can monitor whether staff are attentive, and accidents and oversights are avoided.

Hospitals are like factories, and even the most altruistic medical personnel are worn down by the sheer amount of things they have to do, with rotating shifts and a constantly changing cast of characters. The bureaucracy of the hospital can’t be changed; but it can be counter-acted, by adding people into the situation who have a personal concern for the individual patient.

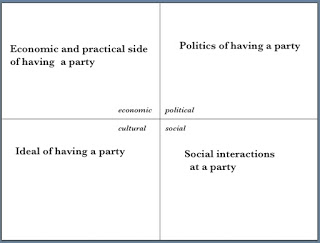

Success or failure: having a party

The 4 REQS can be applied to anything. On a lighter note, what does it take to give a successful party?

The ideal is for a bunch of people to assemble, put all their cares aside, and have a good time. This is the CULTURE box, taken full strength since a party is supposed to be a happy time-out from everything else. Nevertheless the other three boxes have to be taken care of or the party will fail.

The ECONOMICS of a party is its material and practical side, as every party-giver well knows. Where to have the party; getting your house or venue fixed up; the food, the drinks, the music or entertainment if any, etc. That is not to say there is much correlation between how much money and effort is put into the party and how enjoyable it is.

There is little research on this comparison, but there are plenty of instances where very expensive parties fall flat. One kind of bring-down is where the hosts are too obsessed with the material side; another is where the guests are too self-conscious about it and spend their time comparing how lavish things are (or criticizing where they are not) rather than enjoying themselves.

The POLITICS of a party is where it overlaps with conflicts and alliances. Putting a collection of people who don’t like each other in front of a spread of food and drinks will not necessarily produce a happy occasion. That is why traditional hostesses (as in the British upper classes) elaborately strategized their dinner parties, deciding not only who to invite but who to seat next to whom. The shift towards greater casualness and informality since the latter part of the 20th century probably has not raised the level of success of social occasions, because this kind of deliberate concern for whether people will strike it off with each other has largely disappeared. David Grazian’s research on nightlife shows that most of the solidarity is confined to little groups of companions who go out together and make a game out of making any contact at all, however ephemeral, with the opposite sex.

Stressing the ECONOMICS box can’t determine whether a party will be successful, although too little attention to the material input will make it fail.

The POLITICS box works the opposite way, where paying a lot of attention to the right political mix contributes strongly to its success. Invitations which are too automatic run the likelihood of failure. One familiar version is the extended-family holiday gathering where the different relatives may not actually like each other; such gatherings can lead more to conflict than to collective effervescence.

A techno-solution has become widespread in modern times: instead of talking, people who have little to say to each other can all sit and watch TV. Similarly in night clubs extremely loud music not only sets the atmosphere but is a substitute for conversation.

There is a real historical break here, since before around 1950, parties and other festive gatherings did not rely much on conversations. There were traditional ways for getting people participating together: One was dancing in groups. The last remnant, line-dancing, goes back to the dance forms prevalent before the mid-1800s, where men and women maneuvered ceremoniously around the floor in set formations. Then couples dancing separated people into duos, and introduced a new element of political status and conflict over who danced with whom and who was left out. Another participation technique at traditional parties was playing games; the livelier ones had a lot of physical action, such as hurrying for chairs that diminished in number when the music stopped. There were also pretend-games like costume parties; in the 1700s and earlier, the mark of participating in a festive mood was wearing masks, underscoring the time-out from ordinary reality of the event.

Not all party games had this level of collective excitement.

Playing card games was popular since the 1700s. It provided a certain amount of shared attention, but it reduced the collective effervescence the more seriously it was treated, as in upper-middle class people playing bridge after dinner, or masculine gatherings playing poker. The obsessions and conflicts that go along with gambling can turn the fun-party occasion into a fantasy version of the POLITICS box.

Finally, the SOCIAL box. This is the home-ground of a successful party, a state of joyful collective effervescence, shared by (pretty much) everyone present. The key ingredients, as in any interaction ritual, are getting everyone focused on the same thing (something they are all doing together at the party), building up a shared mood (energy, exuberance, excitement), so that it bubbles over into a shared rhythm. Individuals at a good party get each other increasingly into the mood.

The other three boxes-- the ideal of having a party; the material provisions that are consumed; the politics of how people get along with each other-- all these succeed, or fail, because of how they affect the collective effervescence. None of the other boxes will guarantee it;

material inputs like alcohol or other psychotropic substances can affect the energy level, but drunken people can be boring, sad, or contentious rather than happy.

There is a formula for a truly successful collective effervescence. New Year’s celebration in Las Vegas is an example, when people don’t try to say anything significant, just blow your horns, throw streamers at people, hug people you don’t know. This works where everyone knows the tradition and throw themselves into it. This contravenes most of the customs of ordinary life. Everyday life is not like a party because everyday micro-politics runs counter to what is necessary for widely shared collective effervescence. That is one reason why successful parties are a time-out from everyday life. They need special conditions, which can’t be present all the time. If you insist on making your life one endless party, there are sure to be times when the party isn’t a very good one.

Try it yourself

You can analyze anything with the four-requisites model. Religion, education, or family; sports or literature; sex in any of its varieties; going on vacation. You name it. What is its ideal of success? What does it need to succeed, and what happens in the other 3 boxes that makes it fail, or keeps it in a state of conflict? Fill in the boxes:

How much of each requisite is needed? e.g. business start-ups

From the examples given we can see that different kinds of things have different balances among the requisites. Any activity needs a minimum in all four boxes, but beyond that which boxes require the most emphasis depends on what arena you are playing in. It also depends on timing. For some enterprises, the early period needs a different mixture of inputs than later periods.

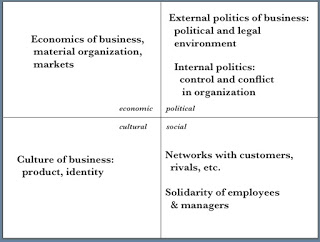

As a sketch, let us consider a business, during the early period of start-up; when it is established as a full-blown player; and the late mature phase when the rest of the world has caught up with it.

CULTURE box: the business’s product, identity, brand, skills and knowledge, and reputation.

ECONOMICS box: its plant, equipment, offices, markets, finances, and organizational structure.

POLITICAL box: on the external side, the state with its political and legal environment, whether supportive or threatening; on the internal side, the alliances and conflicts that make up its power structure.

SOCIAL box: Includes both external and internal networks and how well they are working on the personal level.

External networks connect to supply chain, customers, and recruiting employees. Because the people you do business with are also potential rivals, and everyone could jump ship in either direction, whether these networks work successfully or not depends on emotional flows ranging from mutual enthusiasm to domination to distrust. The same goes for internal relationships, among fellow employees and in the hierarchy of control.

All this depends on how successful interaction rituals are.

Which boxes are most important at which phase of the business’s life-time?

Early start-up stage: The most important factor is in the CULTURE box, since the new business has to establish its identity and name reputation. Economic resources are going to be needed, but if the owners don’t already have a lot of money, the key here lies in the SOCIAL box.

Economic resources are first built up, not from economic performance, but from leveraging social networks; above all, that happens by propagating emotions, so that other people feel a wave of enthusiasm about the new venture.

Compared to this social outburst, the economic aspect isn’t that important at the beginning. The POLITICAL box isn’t crucial at the outset either, as long as the start-up stays out of conflicts, since isn’t big enough to handle them yet.

Established stage: Your reputation, economic position, organization, supply chains are all established. You know where you fit in the field of rivals and competitors, and they know it too. All the boxes are active. The CULTURE box gets less attention, and routine sets in on the SOCIAL side, especially in the internal organization. The ECONOMIC box tends to get the most attention. Successful businesses may develop trouble at this stage-- this is what happened to Apple in the early 1980s, after it had mushroomed into a major corporation, took on managers who made it more similar to the rest of the field, and eventually brought about big internal conflicts that led to Steve Jobs’ departure. Failures in the internal POLITICAL box brought them down.

Over-mature stage: Now the rest of the field has caught up with what you are doing right. Rival firms are all encroaching on each other’s market niches; global competition over cheaper supply chains is intense. The most important box becomes the POLITICAL one, including the financial world as a political realm where coalitions are made and unmade. Pressure comes from financial markets, and the maneuvers of powerful financiers in raids, buyouts, campaigns over share-holder value alternatively forcing spin-offs or acquisitions.

The successful organization at this stage becomes more concerned with external politics than anything else; even organizations which are highly successful in the other three boxes can disappear because of the POLITICAL box.

One-sided theories

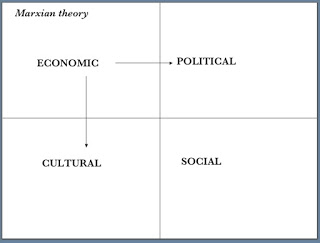

Most theories in the social sciences are one-sided, placing all the emphasis on one box.

Since all the boxes are important, this will usually yield some insight. But it leaves the theory with blind spots.

Marxian theory-- once known as “historical materialism”-- places the prime mover in the economics box. Marxists recognize other boxes exist but regard them as outcomes or screens for economic interests.

Ideology is a set of false beliefs, covering up for the dominant economic interests; ideas themselves are never autonomous, since they are produced by whoever controls the means of mental production (churches, schools, the media, etc.) Politics is an arena where classes struggle for control of the state and the legal system to favor their own interests. All this has a good deal of reality, and materialists have discovered some important causal links. Marxian theory is weak especially in the SOCIAL box. Key processes such as mobilizing political movements, fighting wars, and the success or failure of revolutions cannot be explained in a purely Marxian framework, but need theories about interaction rituals, emotions, and networks.

Economics as a discipline today has the same location as Marxism. (A rival form, institutional economics, argues that what happens in markets is shaped by the political and legal environment, and hence would be located in two boxes.) Rational choice theory in political science, sociology, and psychology attempts more abstractly to reduce everything to the dynamics of the economics box.

Here again its big flaw is obliviousness to emotional processes, to the influence of ideas, and to networks that do not resemble competitive markets.

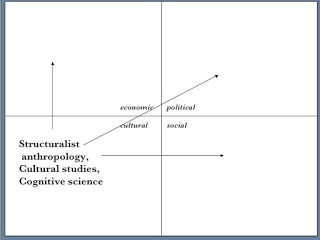

Structuralist anthropology, and a related movement of the late 20th century, cultural studies, claims that the prime mover is the CULTURE box.

This claim gains some respectability from theories in cognitive science that schemas and categories are fundamental in structuring both brains and computers. For structuralists, the culture/cognitive map lays down the blue-print on which societies and social institutions are patterned. The weaknesses of giving primacy to the ideology box are: ignoring the importance of emotions-- an error that cognitive psychologists have begun to rectify, since emotions are key markers of what cognitions are paid attention to. There is also a theoretical dilemma between trapping oneself in a static universe where culture always repeats itself, and recognizing cultural change but being unable to explain it except as a mysterious “rupture,” as theorists like Foucault called it.

To explain changes in culture, the other boxes are needed.

Durkheimian sociology solves these problems by locating primacy in the SOCIAL box. And it spells out the mechanism by which social solidarity, energy, and action is generated (and conversely when solidarity, emotion, and action fail). Interaction ritual (IR) theory reverses the priority between the SOCIAL and the CULTURAL boxes; it is where successful interaction rituals are carried out that the ideas people focus on and talk about become sacred objects, thus making them dominant ideas. (Here Durkheim outflanks Marx.) Why ideologies change is no mystery from this point of view; when the carriers of ideas stop having successful IRs, those ideas fade away.

Durkheimian theory is one of the big pieces for solving the whole puzzle, but it can’t stand alone. To carry out successful IRs, material conditions are needed; so it is subject to inputs from the ECONOMICS box, both in the form of the material resources Marxists are good at analyzing, and the market processes seen by conventional economists. In the past, Durkheimian theorists have tended to downplay conflict, and to regard the POLITICAL box as little more than a place where the norms and ideals of society are enacted. We need all four boxes.

There are other important but one-sided theories in the SOCIAL INTERACTION box. Freud and his followers were especially imperialistic, applying the theoretical dynamics of early family life to remote fields like art and politics. To his credit, Goffman said that he was dealing with only one part of the puzzle.

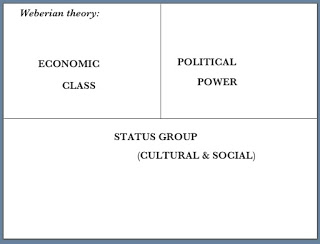

The nearest to recognizing the pervasiveness of multiple causality was Max Weber. In his theory of stratification, he argued against Marx that there are not only economic classes, but divisions by cultural life-style groups (status groups), and by power groups or parties fighting over control of the field of state power. Weberians have elaborated this into a 3-dimensional scheme, in which everything has an economic, social/cultural, and political aspect. Weber merges the social and ideological boxes, since he argues (especially in the history of religions) that every kind of ideal has a social group that is its carrier.

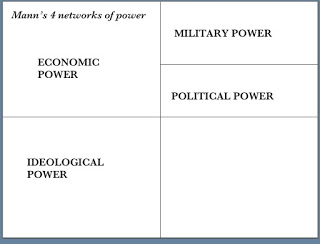

The most important new development of Weber’s 3-dimensional theory is Michael Mann, who elaborates it to four dimensions in The Sources of Social Power. Mann does this by splitting the POLITICAL box into political power (the internal dynamics and penetration of the state), and military power.

Mann thus analyzes world history as a series of shifts in the four sources of power: Ideological, Economic, Political, and Military. (The Social Interaction box gets downplayed.) In Mann's theory, a major revolution must include changes in at least three of these.

Origin of the Four-Requisites model

Sociologists who know the history of our field will recognize that what I am saying is not original, but was stated by Talcott Parsons.

Since Parsons was my undergraduate teacher at Harvard in the early 1960s, there is no mystery about where I have gotten the four-requisites model.

I have made two changes, one minor and one major. Parsons had a much more abstract way of labeling the four boxes (he called them Adaptation, Goal-attainment, Interaction, and Latent pattern maintenance-- hence Parsonian students used to refer to them as the AGIL scheme); and he referred to the four boxes as “pattern variables.”

It is a lot easier to see what we are talking about if we call them ECONOMIC, POLITICAL, SOCIAL INTERACTION, and CULTURE boxes.

The major change is getting away from functionalism. Parsons regarded society as like a biological organism, in which all the parts are like organs that function harmoniously together to keep the organism healthy. Functionalists have trouble dealing with conflict, since there is no analogy in the physiological world. And their theoretical bias is to see everything as contributing to the success of the social organism. I have changed the model to four requisites for a social unit to succeed, without assuming that the requisites will be met. As we have seen in examining medicine, parties, and businesses, they often fail. And they are full of internal dilemmas, so that one box works against the success of another.

The key is to treat everything as a variable: how much and what kinds of material/economic resources, political alliances and conflicts, networks and emotional solidarity, and ideas are there? Our aim is to make the theory explain quantitative differences rather than merely checking off a set of conceptual boxes. As I have suggested, different kinds of social projects have different emphases among the four requisites; and these requisites can change over its life-history.

One-sided theories are popular. They have the practical advantage of making our cognitive world more manageable; and they appeal to feelings of membership in some ideological movement striving to dominate the intellectual world. Their disadvantage is that one-sided theories always fail through their blind spots.

The four-requisites model is a convenient way of dealing with the multi-causal processes that make up the real world. Combining the best theories in each of the four boxes is our most realistic way of explaining what will make anything succeed or fail.

Napoleon Never Slept: How Great Leaders Leverage Social Energy

Micro-sociological secrets of charismatic leaders from Jesus to Steve Jobs

E-book now available at

and

CIVIL WAR TWO Available now at Amazon

REFERENCES:

Among the huge literature on medical sociology, see:

Adam Reich. 2014.

Selling Our Souls: The Commodification of Hospital Care in the United States.

Daniel Chambliss. 1996.

Beyond Caring: Hospitals, Nurses, and the Social Organization of Ethics.

Charles Bosk. 2003.

Forgive and Remember: Managing Medical Failure.

Marshall Meyer and Lynn Zucker. 1989.

Permanently Failing Organizations.

parties:

David Grazian. 2008.

On the Make: The Hustle of Urban Nightlife.

Cas Wouters. 2007.

Informalization: Manners and Emotions since 1890.

David Riesman. 1960. “The Disappearing Host.”

Human Organization

19: 17-27.

business:

For an analysis in terms of networks and Interaction Ritual theory, see

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"MS Pゴシック"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:1 0 16778247 0 131072 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman";} @page Section1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;}

Randall Collins and Maren McConnell, 2015.

Napoleon Never Slept: How Great Leaders Leverage Social Energy

.

published as an E-book at